| THE SHORT VERSION Micro-civic interventions are what happen when people stop waiting for permission. Plant a garden where the vacant lot used to collect trash. Paint the crosswalk kids have been using for years. Put out folding chairs and free coffee every Saturday morning. These aren’t grand gestures—they’re small, immediate fixes that turn neighbors into communities. You can start tomorrow. |

Why Nobody’s Coming to Save Your Neighborhood

I worked fifteen years in municipal government. Started as a planning intern, worked my way up to deputy director of community development. Here’s what nobody tells you about how cities actually work: by the time a neighborhood problem gets studied, budgeted, approved, and implemented, the original complainants have either given up or moved.

I watched this happen over and over. A resident comes to a city council meeting, says their street needs a stop sign because cars blow through at 45 mph and someone’s going to die. Council says they’ll look into it. Staff does a traffic study. Study gets reviewed. Maybe six months later, it goes back to council. They approve funding. It goes into the next fiscal year budget. Construction happens the following spring. Total time: eighteen months minimum. Sometimes three years.

Meanwhile, that resident? Either they moved to a safer street, or—and this happened twice while I was there—someone actually did get hit.

Around 2015, something shifted. People started just… doing things. Not asking. Not waiting. A different kind of civic engagement was emerging—hyper-local activism that didn’t depend on bureaucratic approval. I noticed it first in my own neighborhood. Someone installed a Little Free Library. Then someone else planted sunflowers in the traffic median. Then a group started meeting for coffee every Saturday in the parking lot of the closed grocery store.

None of them had permits. Nobody asked the city first. And you know what? Things got better.

How We Were Taught Civic Engagement Works vs. How It Actually Works Now

| The Textbook Version | What’s Actually Happening | |

| How Often | Vote every 2-4 years, maybe show up to one meeting | Daily texts, weekly action |

| Where | Ballot box, city hall | Your street, that vacant lot, the corner |

| What You Need | Lawyers, lobbyists, years of patience | Three friends, one weekend |

| Results | 3-5 years if you’re lucky | Next week |

The 7 Interventions (Tested, Proven, Stolen Shamelessly)

These aren’t theoretical. I’ve seen every one of these work in multiple cities. Some I helped organize myself after I left city government and realized I could actually get more done as a regular resident than I ever could as an official. Here’s what works.

1. Guerilla Greenery

There’s probably a vacant lot near you. Someone technically owns it—might be the city, might be a bank that foreclosed ten years ago, might be an LLC nobody can track down. Nobody’s maintaining it. It’s full of trash and broken glass and maybe one sad mattress.

Go plant stuff. I’m serious. Get native wildflower seeds, scatter them in spring. Or if you’re feeling ambitious, show up with some friends, clear the trash, add soil, plant things that won’t die immediately. Tomatoes if it’s sunny, ferns if it’s shady, whatever grows in your climate without much help.

A neighborhood in North Philadelphia did this with forty-three vacant lots in one summer. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society studied it afterward—property values went up, crime went down, neighbors reported feeling safer. But the best result was simpler: the lots stopped being dumping grounds. People started treating them like shared space instead of abandoned space.

Is it legal? Depends on your city. Most places, it’s technically illegal. But here’s what I learned working in government: code enforcement is overwhelmed. They’re dealing with actual safety hazards. They’re not hunting down community gardens. If someone complains, you might get a letter. When the time comes, deal with that issue.

2. The Permanent Breakfast

This one’s stolen from Vienna. Every Saturday morning, same time, same place, you set up a folding table in a public spot. Coffee, donuts, whatever. You sit there. You invite people to join you. That’s the whole thing.

First Saturday, you’ll feel ridiculous. Maybe one person stops. Second Saturday, two people. By the sixth Saturday, you have regulars. By three months, those regulars know each other well enough that when someone needs help, they actually help.

I watched this happen in Portland after a bad ice storm. A permanent breakfast group had been meeting for about a year. When the power went out, they already knew who was elderly, who had medical equipment, who needed insulin. They organized wellness checks and resource sharing in about twenty minutes through their group text. The city’s official emergency response took three days to reach that neighborhood. The breakfast crew had it handled in hours because they’d built the engagement infrastructure beforehand.

3. Digital Hyper-Locality

Start a Signal group for your actual physical block. Not your zip code, not your neighborhood association district, your block. Maple Street between 3rd and 4th. That specific. Invite ten people. When someone needs a ladder, they post. When someone’s making soup for twelve and only has three mouths to feed, they post. When someone sees that car that’s been circling suspiciously, they post.

This sounds trivial until someone’s basement floods at 11pm on a Tuesday. My street’s group coordinated four neighbors with wet-dry vacs and one neighbor with a dehumidifier. Total time from SOS to help arriving: eleven minutes. That’s not revolutionary, but it beats waiting until morning and losing everything you stored down there.

The key is keeping it small and specific. Big groups become noise. Small groups become mutual aid networks. You want everyone in the group to live close enough that helping someone takes less effort than ignoring them.

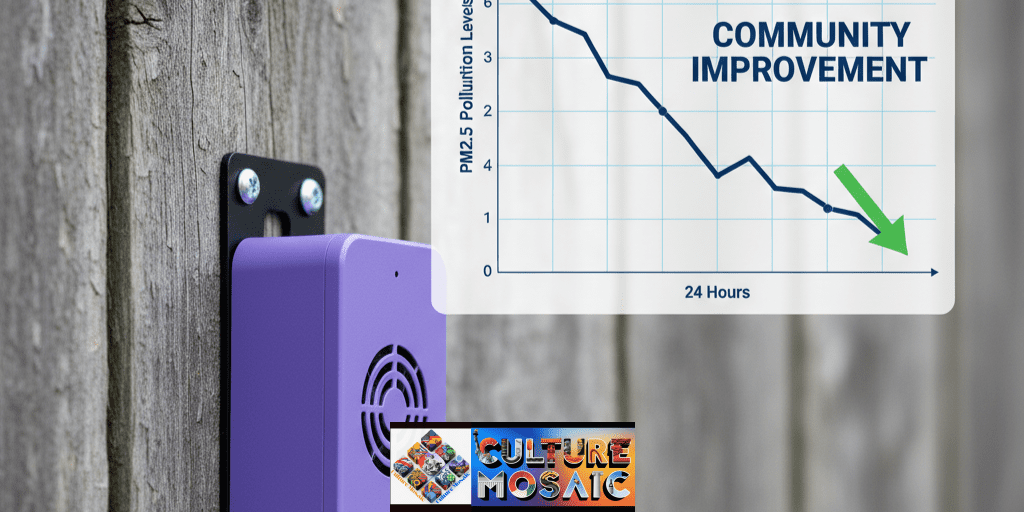

4. Data That Shuts People Up

You can buy air quality sensors now for about seventy bucks. They measure particulate matter, upload data automatically, create public dashboards that anyone can see. A neighborhood in Houston’s Fifth Ward had been complaining about refinery pollution for literal decades. City said the air was fine, residents were exaggerating, sensors at the refinery fence line showed acceptable levels.

Residents pooled money, bought thirty sensors, mounted them on their houses. Turns out the air wasn’t fine. The data was impossible to argue with. Not anecdotes, not feelings, actual measurements. The refinery eventually agreed to better pollution controls because denying the data made them look worse than admitting the problem.

Same approach works for traffic speeds, noise levels, anything measurable. I’m not saying data automatically solves problems. But showing up to a meeting with six months of measurements beats showing up with six months of complaints. People can dismiss complaints. They can’t dismiss properly collected data.

5. Block-Level Participatory Budgeting

Cities do participatory budgeting where residents vote on how to spend public money. Sounds good. Usually isn’t. Too slow, too bureaucratic, the projects that win are often whoever has the best graphic designer on their committee.

Do it yourself on a tiny scale instead. Put up a Google Form: what does our block need? Collect answers. Pick the top three. Figure out the actual cost. Pass a hat or set up a Venmo pool. When you hit the number, do the thing.

A block in Chicago wanted a bench at their bus stop. Kids waiting for school, elderly folks waiting for the bus, everyone standing in the rain because there was nowhere to sit. They asked the city. City said eighteen months minimum, probably won’t happen, budget constraints. Neighbors raised $285 in four days. Bought a bench. Bolted it down. Done.

The city could have forced them to remove it. Instead, they sent someone to verify it was properly anchored so nobody got hurt. Sometimes asking forgiveness beats asking permission.

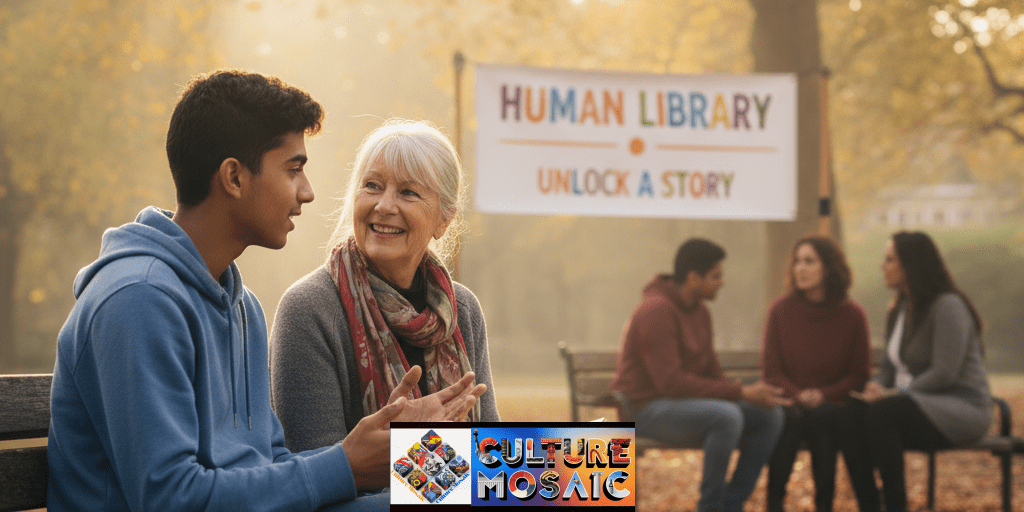

6. The Human Library

Host an event where people can check out other people for fifteen-minute conversations. The guy who’s lived on this block since 1959. The family that immigrated last year. The contractor who built half these houses in the 80s. The teenager organizing climate strikes. Whatever. Just get people talking to each other.

What you’re really attacking is the fundamental isolation problem. People live next door to each other for years and don’t know basic facts about each other’s lives. A human library in Minneapolis connected a Somali refugee family with a retired social worker who’d lived in the same building for thirty years. They didn’t know each other existed. After the event, the social worker helped the family navigate the school system. The family taught the social worker how to cook with spices she’d never tried. They met because someone organized one Saturday afternoon event.

7. Tactical Urbanism (The Fancy Name for Just Fixing Stuff)

This is the big category that includes painted crosswalks, pop-up bike lanes, guerilla bus shelters, temporary plazas made from traffic cones and folding chairs. The basic idea: use cheap, temporary materials to show what’s possible, prove demand exists, then push for the city to make it permanent.

The LA Crosswalk Collective is the best example I know. Traffic crashes are the leading cause of child deaths in Los Angeles. Parents had been requesting crosswalks near schools for years through official channels. The city had a backlog of 10,000 requests. So parents started painting crosswalks themselves. Yellow paint, stencils, done by sunrise.

Some cities painted over them. The parents painted them again. Some cities threatened arrest. The publicity was terrible—city criminalizing parents trying to keep kids safe. Eventually, cities started fast-tracking the legitimate requests instead of fighting the guerilla installations. Several California cities now have programs specifically designed to incorporate community safety improvements quickly. Those programs wouldn’t exist without the painted crosswalks.

Why 2026 Is Different: The Tech Finally Caught Up

The old criticism of micro-civic interventions was always that they couldn’t scale. Too scattered, too temporary, too dependent on individual energy. However, during the past few years, something has changed. The tools got good enough and cheap enough that small actions can actually aggregate into something that matters.

Making Small Visible

Let’s say you organize monthly street cleanups. Twenty people show up each time, you fill bags with trash, things look better temporarily. Great. But how do you prove this matters to the city? How do you demonstrate that regular maintenance reduces illegal dumping and improves property values?

Now you can actually show it. Geotagged before-and-after photos. Participation tracking over time. Simple dashboards showing decreasing dump rates. When you go to the city asking for weekly trash pickup, you’re not just complaining. You’re showing them data proving the neighborhood will maintain what they invest in.

Some cities are building systems to incorporate citizen-generated data into official planning. Not many yet. Boston’s doing it—potholes reported through their app get prioritized faster. That’s a tiny example, but it shows the feedback loop working. Small actions, documented properly, feeding into larger systems.

The Questions People Actually Ask Me

Is This Legal?

Depends completely on what you’re doing. Planting flowers without permission? Technically illegal most places, practically never prosecuted. Painting crosswalks? More serious, you could get charged with vandalism. Setting up a weekly breakfast in a public park? Perfectly legal as long as you’re not blocking anything or selling anything.

The line is intent and proportionality. Are you making things objectively better or worse? Creating safety hazards or solving them? Most cities don’t want to be the bad guys removing community gardens and safety improvements. But you need to be prepared to defend what you’re doing publicly. Document everything. Take photos. Be ready to explain your reasoning.

How Do I Find People?

Look for people who already show up to things. The person at the library meeting. The one organizing the school fundraiser. The neighbor who’s always outside working on their house. Those are your people. Send ten texts. You need three yes responses. That’s enough to start.

Don’t wait to build a coalition before doing anything. Do something small, document it working, then recruit. Success recruits better than any pitch. After my first permanent breakfast, people came up asking how they could help. I didn’t need to convince anyone. They saw it working.

Does This Actually Change Policy?

Yes, but not directly. One garden doesn’t change zoning law. What happens is this: people work together on small things, build trust, develop what Robert Putnam calls bonding social capital. That becomes the foundation for larger organizing. Eventually you have enough people who know each other and trust each other that you can push for actual policy changes and win.

Every major tactical urbanism success started illegal and became policy. The NYC protected bike lanes. The San Francisco parklets. The LA crosswalks. They proved concepts, built public support, then forced formalization. That’s a real pathway, not fantasy.

When Things Go Sideways (They Will)

The City Says Stop

This happens. Have a plan before you start. Sometimes you comply immediately and pivot to something requiring less permission. Sometimes you negotiate—maybe they’ll let you do a temporary version or get a permit retroactively. Sometimes you make them fight you publicly because you know opinion’s on your side.

Which approach depends on your situation. If you’re a longtime resident with deep roots, you can push harder than someone who just moved in. If what you’re doing clearly improves safety, the city has less room to crack down. Use judgment.

Neighbors Hate It

Some people hate change reflexively. Some have legitimate concerns you missed. Learn to tell the difference. If someone’s worried your parklet blocks emergency vehicles, that’s worth addressing. If someone just doesn’t like that things are different, acknowledge their feelings but keep going.

Build your coalition broad enough that isolated critics can’t derail you. If forty people support something and three oppose it, move forward. If it’s fifty-fifty, rethink or modify. But don’t let one loud person stop something the whole block wants.

You Burn Out

Most common failure mode. You start strong, burn out after three months, everything falls apart. The solution is building sustainability in from the start. Don’t depend on one person. Rotate responsibilities. Keep scope manageable. Better to do one thing consistently for a year than ten things for two months.

Three Examples That Prove This Works: Micro-Civic Interventions

Park(ing) Day: One Space Changed Cities

2005, San Francisco. A design studio paid the meter for a parking space, rolled out sod, added a bench. Called it a park for eight hours. That was the whole intervention. One parking space. One day.

Now Park(ing) Day happens in hundreds of cities every September. More important, it led to permanent parklet programs. San Francisco has over fifty now. Philadelphia, Seattle, Austin, dozens of others. The idea seems obvious in hindsight. But someone had to prove parking spaces could become something else first.

Birch Street: Duct Tape to Policy

Boston residents used duct tape and milk crates to turn a street into a pedestrian plaza. Completely temporary. Looked janky. But people used it. Kids played there. Neighbors sat and talked.

City came to remove it and found themselves stuck. Take down something that’s working and making people happy? Eventually they authorized permanent construction using almost the exact design the community created with duct tape. The temporary installation was proof of concept. Without it, those residents would still be in meetings requesting a plaza and being told there’s no budget.

The Philly Lot Transformation

The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society studied what happened when North Philly residents greened forty-three vacant lots in one summer. Crime dropped. Property values rose. But the real change was subtler. Neighbors started maintaining the lots together. They knew each other’s names. They watched out for each other’s kids. The lots went from spaces that divided the neighborhood to spaces that connected it.

That’s what engagement infrastructure looks like when it works. Not dramatic, not revolutionary. Just people who know each other, trust each other, help each other. Everything else builds from that foundation.

What You Do Next

Pick one intervention. Not all seven, one. Text three people tonight and ask if they’re interested. Give yourself two weeks to try it. Take before-and-after photos. See what happens.

That’s how this works. Not with a master plan or a steering committee or years of preparation. With you, three friends, two weeks, one concrete thing.

Your neighborhood’s waiting. Go fix something.

Quick Start: Do This Tomorrow

Week 1: Pick Your Thing

Walk your block. Actually walk it, don’t drive. Look for the one thing that bugs you most. Not the biggest problem, the one that makes you personally angry every time you see it. That’s your target.

Ask yourself: could three people fix this in one weekend? If yes, that’s your intervention. If no, pick something smaller. You want quick, visible, undeniable improvement.

Week 2: Recruit Your Core

Text ten people. Friends, neighbors, that person you always see at the coffee shop. Say: I’m doing [specific thing] on [specific date]. Want to help? You need three yes responses. If you get them, you’re good. If not, adjust your pitch or pick a different thing.

Week 3: Just Do It

Saturday morning. Be there at the time you said. Bring what you need. Take before photos. Do the thing. Take after photos. Thank everyone who showed up. Post the photos somewhere. Done.

Week 4: Decide If You’re Doing It Again

Did it work? Did people notice? Did it make things actually better? If yes, do it again but slightly bigger. If no, try something different. Either way, you learned something.

Neighborhood Audit Checklist: Micro-Civic Interventions

Use this to figure out what your neighborhood actually needs. Walk it. Don’t drive, walk. You’ll see things you’ve been ignoring for years. Take notes. Take photos. This becomes your action plan.

Physical Stuff

- Where are the vacant lots? Who owns them? What’s growing there now?

- Which intersections make you nervous crossing? Why?

- Where do people actually cross? Is there a crosswalk there?

- Which streets feel like racetracks? Could anything slow them down?

- Where would you sit if there was somewhere to sit?

Green Space

- Which blocks have zero trees? Why?

- Where could you put planter boxes? Raised beds? Window boxes?

- Do you smell weird stuff? Chemical? Exhaust? Sewage? Where?

- Where does water pool when it rains?

- Where does trash pile up? Why?

People

- Where do people naturally gather? Or do they not?

- Is there anywhere to hang out that isn’t someone’s private house?

- Do old people and young people ever interact?

- Who looks lonely?

- Do kids play outside? Why or why not?

Resources

- How far to real food? Not convenience stores, actual groceries?

- Who has tools? Who needs them? Could they share?

- What skills exist that people don’t know about?

- Which businesses do people use? Which sit empty?

Memory

- Who’s been here longest? Do young people know their stories?

- What happened here that people should remember?

- Where could art go?

- What makes this place different?

Now What?

After you walk and fill this out:

- What bugs you most? Not biggest problem, the one that personally drives you crazy.

- Could you fix it in two weeks with three people? If not, pick something smaller.

- Who are the three people? Write their names. Text them tonight.

- What do you need? Be specific. Actual things, actual costs.

- How will you know it worked? What will be different?

Stop reading. Start doing.

FAQs: Micro-Civic Interventions

What exactly are micro-civic interventions?

Small things neighbors do together to fix problems immediately instead of waiting for permission. Guerilla gardens. Pop-up bike lanes. Community fridges. Street murals. Permanent breakfasts. Tool libraries. The defining thing: you just start instead of spending years requesting approval.

Is this legal?

Sometimes yes, sometimes no, usually complicated. Planting flowers without permission is technically illegal most places but nobody prosecutes. Painting crosswalks is more serious. Permanent breakfast is perfectly legal. Know your rules, document everything, be ready to defend publicly. Most cities would rather work with you than against you if you’re obviously trying to help.

I’ve never organized anything. Where do I start?

Pick the absolute simplest thing. Set up one permanent breakfast. Start one Signal group. Put up one Little Free Library. Something requiring almost no coordination and zero money. See if anyone joins. If yes, now you have two people for something bigger. If no, try something different. Don’t wait to feel ready. You learn by doing.

Does this actually lead to policy change?

Yes. Not directly—one garden doesn’t change zoning. But small actions build trust and social capital. That becomes the foundation for bigger organizing. Every major tactical urbanism success started illegal and became official policy. NYC bike lanes. San Francisco parklets. LA crosswalks. They proved concepts, built support, forced cities to formalize them. That’s a real pathway.

How much does this cost?

Almost nothing for most interventions. Guerilla garden: maybe forty bucks in seeds. Permanent breakfast: cost of coffee and donuts. Little Free Library: build from scrap or buy for under a hundred. Digital coordination: free. Most expensive thing in this article is air sensors at seventy to eighty dollars each. If money’s the barrier, you’re picking the wrong intervention. Choose something cheaper.