You don’t need a degree in microbiology or expensive equipment to get started with traditional food preservation. Just grab a cabbage, some salt, and give yourself ten minutes. That’s it. This weekend, you’re making something your great-grandmother would recognize instantly.

Why Bother With Traditional Food Preservation?

Look, I spent years in food science labs studying preservation methods. We’d run tests on commercial products, measure pH levels, count bacterial colonies. And you know what I kept thinking? Our ancestors nailed this without any of that equipment.

Traditional food preservation is just smart manipulation of nature. You’re controlling water, acidity, temperature, and bacteria. Sauerkraut does three of these at once, which makes it pretty much foolproof once you understand what’s happening.

The stuff you buy at the store? Usually not even fermented anymore. They add vinegar to fresh cabbage, pasteurize it, and call it a day. Tastes okay, sure. But you’ve killed off everything that makes fermented food worth eating.

Real sauerkraut is alive. Imagine tiny bacteria, like industrious little workers, settling on the surface of cabbage leaves. These Lactobacillus bacteria feast on the natural sugars present in the cabbage, transforming them into tangy lactic acid as they go about their business. This fascinating process not only preserves the cabbage but also adds a delightful flavor that we love in fermented foods! That acid is what preserves everything. Plus you get billions of beneficial bacteria in every forkful, which your gut actually needs.

What You Actually Need

Stop overthinking this. Here’s your shopping list:

Cabbage: Get one medium head, about 2 pounds. Organic is better because pesticides can mess with the bacteria, but regular cabbage works too. Just wash it well.

Salt: Sea salt or Himalayan pink salt. Not iodized table salt. The iodine and anti-caking agents will screw up your ferment. You need about 3 teaspoons for a 2-pound cabbage.

Equipment: One quart jar (wide mouth is easier), a sharp knife, a bowl, and a kitchen scale if you have one. That’s literally it.

How to Actually Make Sauerkraut

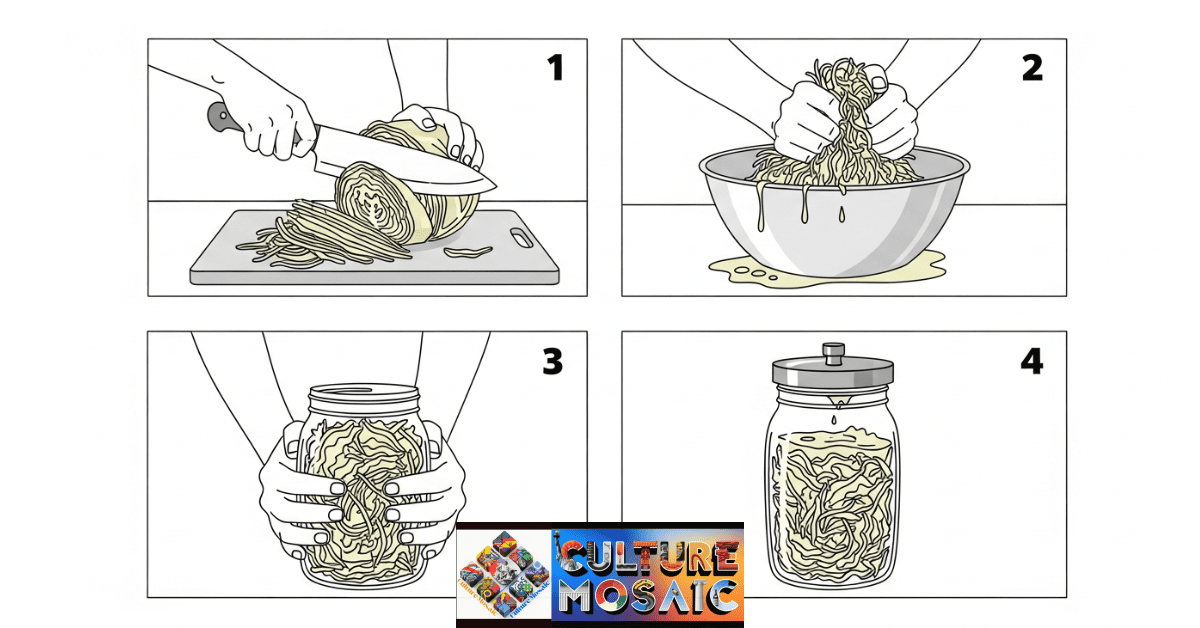

Cut the Cabbage

Peel off the outer leaves and save them. Start by cutting the cabbage into quarters and remove the tough core from each piece. Then slice it thin, maybe an eighth of an inch. Doesn’t have to be perfect, but try to keep the pieces roughly the same size so everything ferments evenly.

Weigh your shredded cabbage. For every pound, you want about 1.5 teaspoons of salt. That’s roughly 2% salt by weight, which is the sweet spot for traditional food preservation. Too little and you risk spoilage. Too much and fermentation slows to a crawl.

Add Salt and Get Messy

Dump the cabbage in a big bowl. Sprinkle your measured salt over it. Now comes the fun part.

Dig your hands in there and start squeezing. Really squeeze it. You’re breaking down the cell walls to release juice. After about five minutes, you’ll have a pool of liquid at the bottom and the cabbage will look wilted and sad. That’s exactly what you want.

This is traditional food preservation at its most basic. When salt meets cabbage, something fascinating happens: it draws water out of the cabbage through the process of osmosis. It’s like the cabbage is shedding its moisture in response to the salt, creating a delicious transformation. That salty water becomes your fermentation brine. No added liquid needed.

Pack It Tight

Grab handfuls of the cabbage and stuff them into your jar. Press down hard with your fist after each addition. You’re trying to eliminate air pockets and make sure the cabbage is completely covered by its own juice.

Pour in any liquid left in the bowl. Take one of those outer leaves you saved and tuck it over the top of the shredded cabbage. This acts as a barrier to keep the small pieces from floating up.

If you have a small jar or a clean rock, put it on top of that leaf to weigh everything down. It’s essential to keep the cabbage fully submerged in the liquid to ensure optimal flavor and preservation. This is crucial for traditional food preservation because exposed cabbage can mold.

Cover the jar loosely. You want gases to escape but bugs to stay out. A lid set on top without screwing it down works fine.

What’s Happening in That Jar

Here’s the cool part. When you pack that jar, you’re setting up a predictable sequence of microbial events.

First couple days, whatever oxygen is left gets consumed by aerobic bacteria and yeasts. The environment goes anaerobic fast.

Days three through five, certain Lactobacillus species take over. They start cranking out lactic acid, plus some CO2 and a bit of acetic acid. The pH drops from around 6 down to 4.5. You’ll see bubbles.

After about a week, different Lactobacillus species dominate. These guys are more efficient. They convert sugars almost exclusively into lactic acid, and the pH drops to 3.5 or so. That’s well into the safe zone for traditional food preservation.

Below pH 4.6, the spores that cause botulism can’t germinate. Most spoilage bacteria can’t survive either. The acid does the preserving.

Watching It Ferment

Stick your jar somewhere between 65 and 75 degrees. Room temperature, basically. Warmer speeds things up but can make softer kraut. Cooler takes longer but usually gives you a crisper result.

First few days, you’ll see small bubbles. The brine gets cloudy. Smells like cabbage still, maybe slightly sour.

Middle of the week, fermentation ramps up. More bubbles, the cabbage changes color a bit, and it starts smelling legitimately sour and pickle-like. Taste it if you want. It’s safe at any stage.

After a week or so, things calm down. The flavor mellows out and gets more complex. Most people like their traditional food preservation results after about 7 to 10 days, but you can go longer if you want it more intense.

When it tastes good to you, screw the lid on tight and move it to the fridge. Cold basically stops fermentation but keeps the bacteria alive.

When Things Go Weird

Sometimes you get a thin white film on top. That’s Kahm yeast, not mold. It’s harmless but can make things taste a little off. Just skim it off and make sure your cabbage stays submerged. Happens to everyone doing traditional food preservation.

Actual mold is fuzzy and colored. Green, black, pink, whatever. If you see that, it means some cabbage got exposed to air. You can sometimes scrape off a small moldy spot with the cabbage around it and be fine. But if it’s everywhere, toss it and start over.

Mushy sauerkraut usually means too much salt or too much heat. Stick to 2% salt and room temperature for best results with traditional food preservation.

If it smells rotten, not sour, something went wrong. This is rare if you use enough salt and keep things submerged, but trust your nose. Fermentation smells tangy. Rot smells nasty.

This Works Everywhere

Every culture figured out traditional food preservation in some form. Koreans make kimchi using the same basic process. Japanese have tsukemono. Middle Eastern pickles, Eastern European ferments, Chinese paocai. All the same idea: salt, vegetables, time, and beneficial bacteria.

Cold climates developed slower ferments with milder flavors. Hot climates needed more salt to slow things down. But the food science stayed the same across all these traditional food preservation methods.

Before refrigeration, this stuff kept people alive. It’s how they survived winters, crossed oceans, and got through bad harvests.

Other Ways People Preserved Food

Fermentation is just one approach to traditional food preservation. Here are the others:

Drying: Remove enough water and bacteria can’t grow. You need to get moisture content below about 15%. Sun-dried tomatoes, jerky, dried fruit. Works great, been around forever.

Heavy Salting: Pack something in 15 to 25% salt and the osmotic pressure alone prevents spoilage. Salt cod and country ham use this method in traditional food preservation.

Smoking: Dries the food while depositing antimicrobial compounds from the smoke. Formaldehyde, phenols, organic acids. Traditional smoked fish and bacon were preserved this way before anyone knew the chemistry.

Cold Storage: Keep vegetables just above freezing with high humidity. Slows down respiration and enzyme activity. Root cellaring is passive traditional food preservation.

Try More Vegetables

Once you’ve got sauerkraut down, the same traditional food preservation technique works on tons of other vegetables. Carrots, beets, radishes, green beans, peppers. All ferment beautifully with salt and time.

You can add spices too. Caraway seeds are traditional with kraut. Juniper berries add complexity. Garlic, dill, peppercorns. Experiment and see what you like.

Each batch teaches you something about how bacteria behave, how flavors develop, and how traditional food preservation actually works in practice.

Why This is Safe

People worry about food safety with fermentation. I get it. But traditional food preservation using lacto-fermentation is remarkably safe when done right.

The acid level alone prevents pathogenic bacteria. You naturally hit pH 3.5 to 4.0, which is too acidic for the bad guys.

The beneficial bacteria outcompete anything harmful for nutrients. The salt inhibits spoilage organisms but supports Lactobacillus. And the lack of oxygen prevents molds and aerobic bacteria.

Multiple barriers working together. That’s why documented cases of illness from properly fermented vegetables basically don’t exist in the scientific literature on traditional food preservation.

Make This a Habit

Start simple. One jar. Watch what happens. Taste it every couple days to see how the flavor changes. Write down what you did and what you liked.

Then make another batch and change one variable. Try red cabbage. Add caraway. Ferment it longer. See what works for your taste.

This isn’t about following recipes perfectly. It’s about understanding the principles behind traditional food preservation so you can adapt and troubleshoot on your own.

Your great-grandmother didn’t have a pH meter. She just knew what worked. You can develop that same intuition.

Frequently Asked Questions About Traditional Food Preservation

How long will my sauerkraut keep?

In the fridge, properly fermented kraut lasts six months easily, often longer. The acidity prevents spoilage. It might get a bit more sour over time as fermentation continues slowly, but it stays safe.

What if I don’t have a scale to measure salt?

Use about 1.5 teaspoons of salt per pound of cabbage. It’s not as precise, but it works. Traditional food preservation happened for thousands of years before kitchen scales existed. Your ancestors eyeballed it.

Can I get botulism from homemade sauerkraut?

No. Botulism needs low acid conditions, and your fermented kraut sits around pH 3.5. Way too acidic. Plus the salt concentration helps. This combination makes botulism impossible in traditional food preservation through fermentation.

Why isn’t my fermentation bubbling?

Could be a few things. Chlorinated tap water can inhibit bacteria. Temperature below 60 degrees slows everything down. Not enough salt or too much salt both cause problems. Make sure you’re using plain salt and filtered water for traditional food preservation.

Is this better than taking probiotic pills?

Research shows good sauerkraut contains anywhere from 10 million to a billion beneficial bacteria per gram. That’s often more diverse than supplements, plus you get the other benefits of traditional food preservation like increased vitamins and better mineral absorption. But individual results vary.