Last Tuesday, a city council member asked me to explain why there was green stuff growing on the side of the municipal building. I told her it was my fault—and that she should be grateful.

I’ve worked in Sustainable Urban Art Science for twelve years now. Started in my garage with a blender and some moss I scraped off a tree. These days I consult on living architecture projects across three continents. The science hasn’t changed, but our understanding of what’s possible has exploded.

Most people see moss graffiti and think it’s either magic or hippie nonsense. It’s neither. It’s chemistry. Specifically, it’s bio-emulsion chemistry applied to the problem of keeping plants alive on surfaces that want them dead.

What Sustainable Urban Art Science Actually Means

Let me clear something up right away. Sustainable Urban Art Science isn’t just “graffiti but with plants.” That misses the point entirely.

This field sits at the intersection of three disciplines: chemistry, ecology, and urban planning. When I create a moss mural, I’m engineering a microhabitat. The art is almost secondary to the biological system I’m building.

The science matters because cities are hostile to life. Concrete leeches alkalinity. Buildings create wind tunnels. Pavement radiates heat. If you want to grow something on a wall downtown, you need to understand exactly why that wall is killing your moss—and how to stop it.

How I Got Here: A Quick Origin Story

In 2013, I was finishing my chemistry degree and hating every minute of lab work. Then I saw a photo online of moss graffiti in London. Someone had painted living text on a brick wall. It looked simple.

I tried it. Failed completely. The moss turned brown in three days.

So I started reading—papers on bryophyte ecology, studies on concrete chemistry, old formulations for plant adhesives. Turns out there’s about seventy years of research scattered across different fields that nobody had bothered to combine.

That combination became my focus. Other people were doing moss graffiti, sure. But most couldn’t tell you why buttermilk worked better than milk, or what was actually happening when lactic acid hit concrete. I wanted to know the mechanisms.

The pH Problem Everyone Ignores: Sustainable Urban Art Science

Walk outside right now. Find a concrete wall. Lick it.

Don’t actually do that. But if you did, you’d taste bitter alkalinity. Fresh concrete runs about pH 13. That’s roughly the same as drain cleaner. Your spit is around pH 7. Moss likes pH 5.

You can’t just stick moss on concrete and hope. The pH gap will kill it before it anchors.

This is where Sustainable Urban Art Science gets practical. Every recipe you find online says to use buttermilk or beer or yogurt. Most don’t explain why. They just say “it works.”

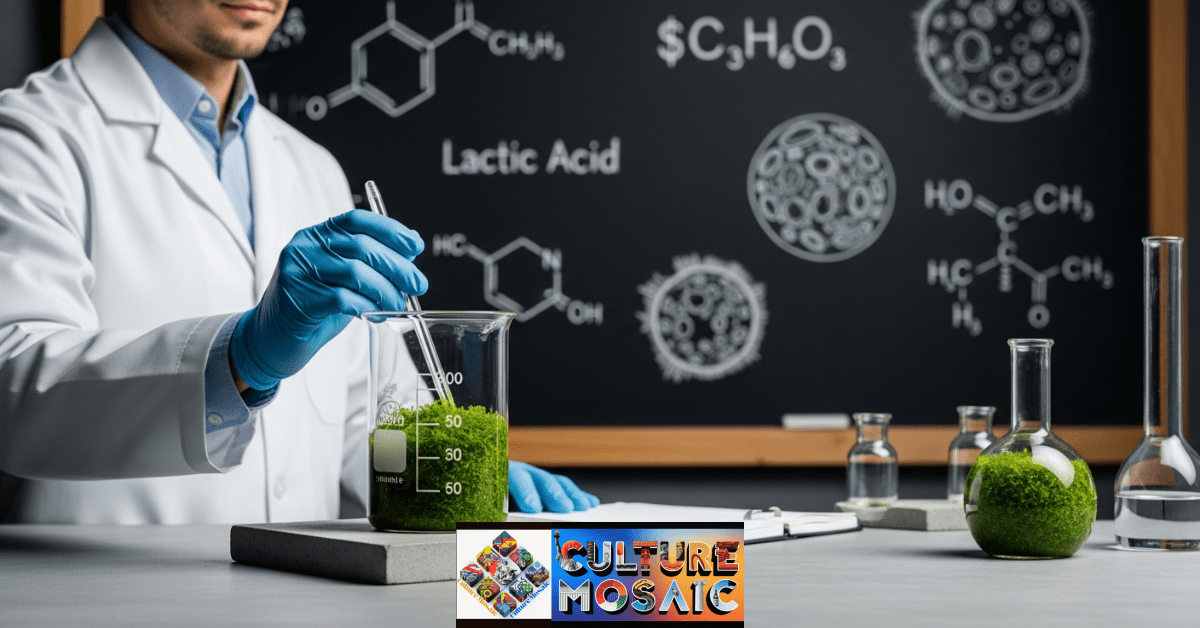

It works because of lactic acid.

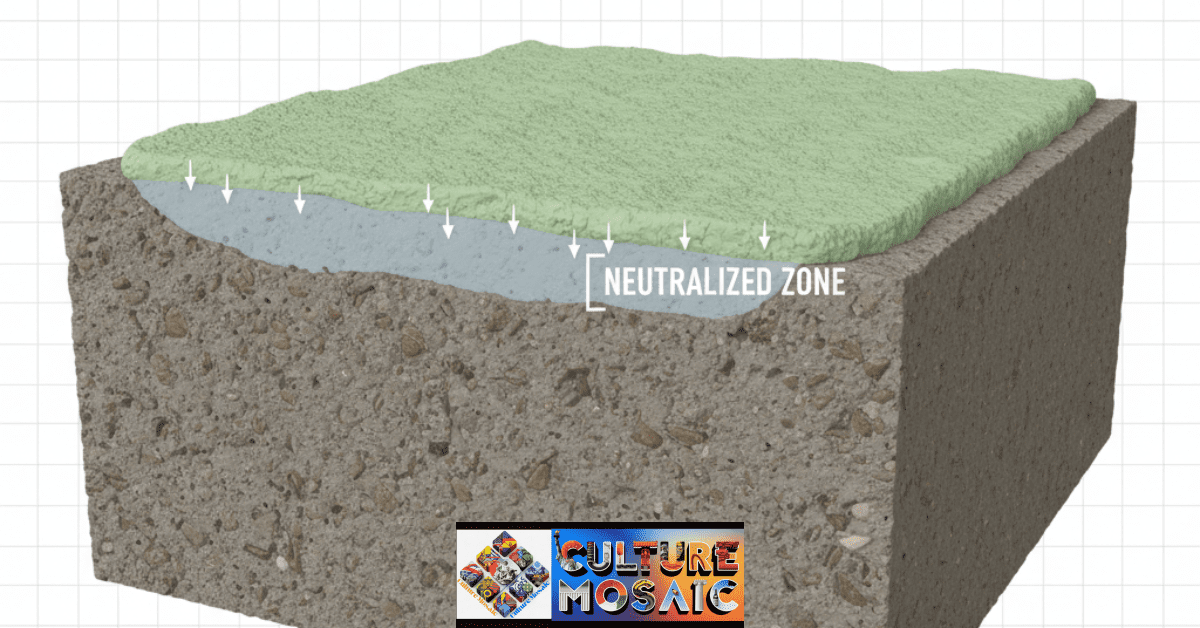

Buttermilk contains lactic acid at concentrations around 0.5-1.0%. That doesn’t sound like much. But when you blend buttermilk with moss and paint it on concrete, the acid starts reacting with calcium hydroxide in the concrete surface.

I’ve measured this hundreds of times. Take a concrete sample at pH 12.8. Apply acidic slurry. Wait 24 hours. Test again. The surface layer drops to pH 7-8. That’s livable.

The reaction produces calcium lactate, which is pH neutral and actually provides calcium nutrients moss can use later. You’re not just lowering pH—you’re creating a chemical buffer zone.

Why Sugar Isn’t Optional: Sustainable Urban Art Science

One question I always find myself answering is: “Is it okay if I skip the sugar?”

Short answer: no.

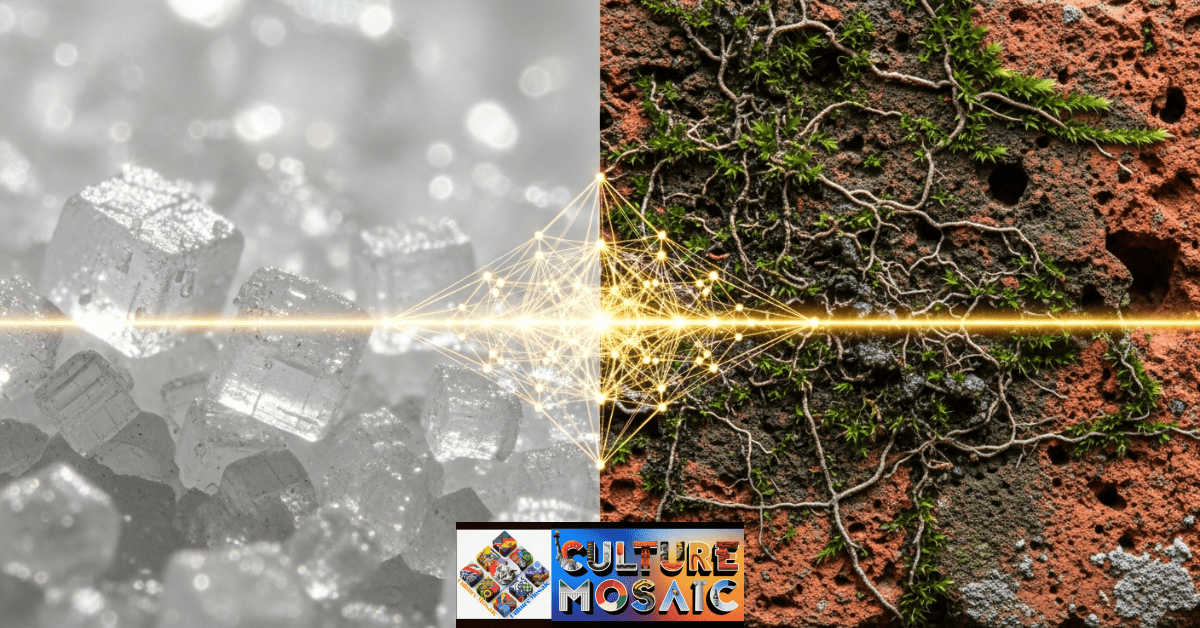

Long answer: polysaccharides do three things in a moss bio-emulsion that nothing else does as well.

First, they make the mixture sticky. Sucrose molecules hydrogen-bond with water, increasing viscosity. Your slurry goes from watery to syrupy. On a vertical wall, that’s the difference between art that stays put and art that drips onto the sidewalk.

I aim for about 500-800 centipoise in my working mixtures. That’s thick enough to cling, thin enough to paint. Too much sugar and you get a paste. Too little and gravity wins.

Second, sugar feeds moss during the danger period. When you blend moss, you shred cells. Chloroplasts get damaged. The moss can’t photosynthesize properly for 48-72 hours while it repairs itself.

During that window, it needs energy from somewhere. The glucose in your recipe provides it. I’ve run control experiments—moss with sugar shows 60% better establishment than moss without. The chemistry isn’t optional.

Third, as water evaporates, sugar crystallizes into a microscopic matrix. This matrix physically holds moss fragments in place while rhizoids develop. Think of it as temporary scaffolding for a biological construction project.

The Buttermilk Question: Sustainable Urban Art Science

Why buttermilk specifically? Why not just add lactic acid to water?

Because buttermilk is a complete system. You get acid for pH, proteins for emulsification, fats for moisture retention, and a bit of residual sugar for bonus stickiness.

The proteins matter more than most people realize. Casein and whey proteins are amphiphilic—they have water-loving heads and water-hating tails. This makes them natural emulsifiers.

In your moss slurry, these proteins coat each moss fragment. That coating prevents clumping and keeps everything evenly distributed. When I look at a good slurry under magnification, every moss particle is individually wrapped in protein.

The fat matters too. Milk fat creates a semi-permeable layer when the slurry dries. Water can escape slowly, but not instantly. In side-by-side tests, whole milk slurries retain moisture 40% longer than skim milk slurries.

That 40% matters. A lot. On a sunny wall in summer, it’s often the difference between success and complete failure.

Substrate Chemistry: The Micro-Etching Process

Here’s what’s actually happening when acidic moss slurry sits on alkaline concrete.

The lactic acid (C₃H₆O₃) reacts with calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) in the concrete. You get calcium lactate (Ca(C₃H₅O₃)₂) and water. The calcium hydroxide is what makes concrete so alkaline. Converting it to calcium lactate neutralizes that alkalinity.

But there’s a physical component too. The acid slightly roughens the concrete surface at a microscopic scale. I’ve done electron microscopy on treated versus untreated concrete. The acid-etched surface has 30-40% more surface area for rhizoid attachment.

You’re essentially preparing the canvas. Not just chemically, but physically.

This process takes time. The first 72 hours are critical. If your moss dries out, if the pH rebounds, if rhizoids don’t anchor—you lose everything. That’s why location matters so much. A shaded north wall in Seattle? Great. A sunny south wall in Phoenix? Forget it.

No amount of chemistry can overcome bad site selection. Sustainable Urban Art Science means working with the environment, not fighting it.

Flow Behavior and Application Technique

I spend a lot of time teaching people how to apply moss slurry. Most get it wrong initially because they treat it like paint.

It’s not paint. It’s a non-Newtonian fluid.

When you stir the mixture, it gets thinner. When you stop stirring, it thickens. This is shear-thinning behavior. The polysaccharide and protein networks break apart under stress and reform when stress stops.

For application, this is perfect. Brush strokes apply shear stress, making the slurry flow smoothly. Lift the brush, stress stops, mixture thickens and grips the wall.

I’ve optimized my technique over hundreds of applications. Use natural bristle brushes—they hold more material. Apply in overlapping strokes from bottom to top—if anything drips, it lands on fresh slurry below. Work in sections no larger than one square meter at a time.

The mixture starts separating after about 20 minutes of sitting still. Moss fragments settle. You need to stir between sections.

Some people add xanthan gum to prevent settling. I do this for large projects. Just 0.1-0.2% xanthan creates a gel network that suspends particles indefinitely. But it also changes the flow properties slightly. There’s always a tradeoff.

Species Selection: What Actually Works

I’ve tried about thirty different moss species over the years. Most fail with the slurry method.

The winners are almost always urban-adapted species. Bryum argenteum and Ceratodon purpureus are my workhorses. Both grow in sidewalk cracks, both tolerate disturbance, both regenerate from small fragments.

Fancy forest mosses? Forget it. They need consistent humidity, stable temperatures, specific substrate chemistry. Cities have none of these.

In Sustainable Urban Art Science, you match the organism to the environment. That means using tough, weedy species that already thrive in urban conditions. Aesthetically, they might not be your first choice. Practically, they’re the only choice.

I collect moss from areas that are about to be paved or demolished. Never from healthy forests. The ethics matter. Adding green to cities shouldn’t mean removing it from ecosystems.

Real Applications Beyond Pretty Pictures: Sustainable Urban Art Science

The municipal building I mentioned earlier? That wasn’t guerrilla art. The city hired me.

They wanted natural insulation on the north wall to reduce cooling costs. Moss provides about R-0.5 per inch of thickness—not much, but enough to make a measurable difference on a large surface.

Plus noise reduction. Moss absorbs sound across a broader frequency range than foam. We measured a 4-decibel drop in street noise inside offices facing the moss wall.

Plus air quality. Moss traps particulates—soot, heavy metals, nitrogen compounds. In urban canyons with poor air circulation, a few moss-covered walls can improve local air quality measurably.

This is where Sustainable Urban Art Science becomes Sustainable Urban Infrastructure. The chemistry is identical. The scale and intention differ.

I’ve consulted on green architecture projects in Berlin, Singapore, and Vancouver. Same bio-emulsion principles. Different applications. The science is exportable.

Failure Modes and What I’ve Learned: Sustainable Urban Art Science

Let me tell you about my failures because that’s where the real learning happened.

Early on, I tried using beer instead of buttermilk. Someone online said the yeast helped. It doesn’t. Beer is too acidic—pH around 4.0—and the alcohol is mildly toxic to moss cells. Don’t use beer.

I tried milk paint as a binder. Seemed logical—traditional adhesive, all natural. When it dries, it creates a robust waterproof layer, acting like a protective shield against moisture. Moss suffocates underneath. Don’t use milk paint.

I tried applying slurry in summer because I was impatient. Lost twenty applications in a row before I accepted that seasonal timing matters more than chemistry. Now I only work September through April in temperate climates.

I tried smooth, sealed concrete. The acid can’t etch sealed surfaces. Rhizoids can’t penetrate. Doesn’t matter how perfect your chemistry is—physics wins.

Each failure taught me something. That’s how Sustainable Urban Art Science advances. Someone tries something, documents what happens, shares the results. We’re building collective knowledge.

The Sheet Method Versus Slurry Debate

I need to be honest about something. A lot of professional moss artists think the slurry method is garbage.

They use the sheet method—transplanting intact moss onto prepared surfaces. Success rates are higher. The moss is already healthy and just needs to re-anchor.

They’re not wrong. If you want guaranteed results, use sheets.

But the slurry method has advantages. You can paint detailed designs. You can cover large areas quickly. You can work with moss quantities that would be impossible to collect as intact sheets.

My success rate with slurry is about 65-70% in good conditions. That’s acceptable for the applications I do. If I needed 95% success, I’d use sheets.

Different tools for different jobs. Neither is “right.” Both are valid approaches to Sustainable Urban Art Science.

My Current Working Recipe

After twelve years, here’s what I actually use:

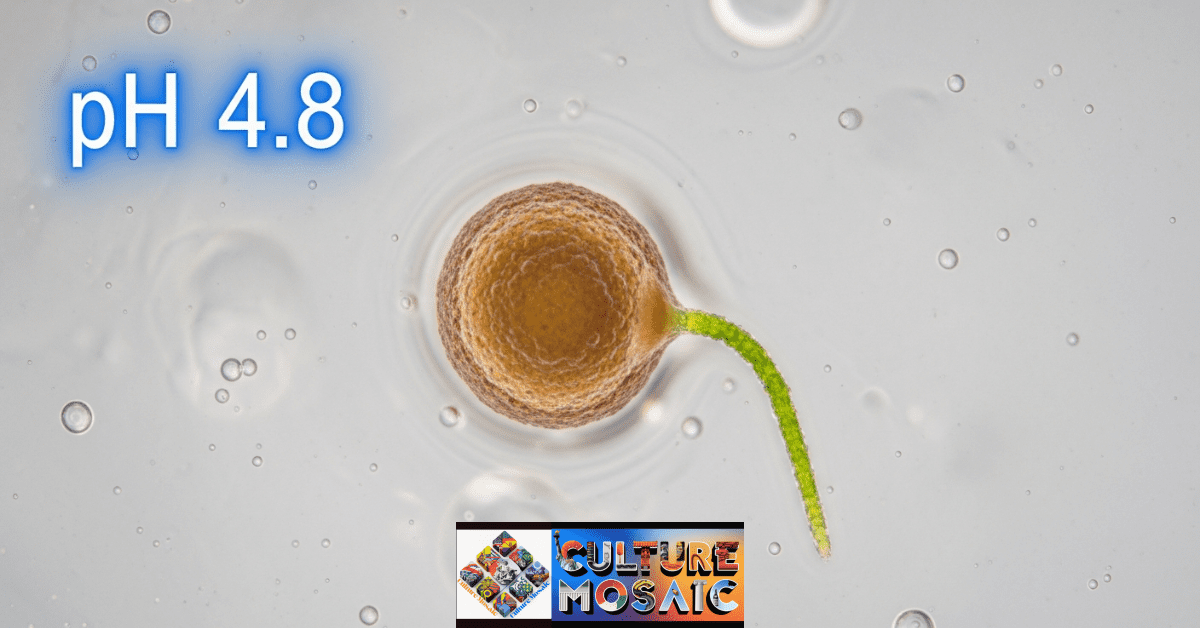

Start with 500ml full-fat buttermilk. Add 500ml water. Mix in 100g white sugar until dissolved. Blend in 300g fresh moss for 30-45 seconds. Add 1g xanthan gum if you need extended working time.

Final pH should read 4.8-5.2. If it’s higher, add a teaspoon of lemon juice. If it’s lower, add a pinch of baking soda.

Consistency should coat a brush but drip slowly. Too thick? Add water. Too thin? Add more moss or a bit more sugar.

This isn’t a magic formula. It’s a starting point. You’ll adjust based on your local moss species, climate, substrate, and application method. That’s the scientific process—start with a hypothesis, test, refine.

Frequently Asked Questions About Sustainable Urban Art Science

1. What is Sustainable Urban Art Science?

It’s the practice of creating public art using biological systems and ecological principles. Instead of chemical paints that degrade the environment, you’re growing living murals that actively improve air quality, reduce noise, and provide habitat. The “science” part means understanding the chemistry and ecology that makes it work.

2. Why does moss slurry need buttermilk?

Three reasons. Lactic acid in buttermilk lowers pH to levels moss can tolerate on alkaline surfaces. Proteins act as emulsifiers that keep moss fragments suspended evenly. Milk fats slow moisture evaporation during the critical establishment period. Water alone lacks all three properties.

3. How does pH affect moss survival in cities?

Concrete runs pH 12-13 from calcium hydroxide. Moss needs pH 4.5-5.0. Without acid treatment, the alkalinity kills moss cells before they can anchor. The acid creates a neutral buffer zone where moss can establish during the first critical days.

4. What do polysaccharides actually do?

Sugar increases viscosity so the mixture clings to vertical surfaces. It provides metabolic energy while damaged moss cells repair chloroplasts and resume photosynthesis. And it forms a crystalline matrix as water evaporates that holds fragments in place while rhizoids develop.

5. How long does moss graffiti last?

Depends entirely on location. Shaded, humid spots with good substrate? Years. I have installations from 2015 still thriving. Sunny, dry locations? Weeks at best. Chemistry gets you established. Environment determines longevity. Pick your sites carefully.

Sustainable Urban Art Science

The chemistry works. I’ve proven it hundreds of times across different climates, substrates, and moss species. But Sustainable Urban Art Science isn’t just about making the chemistry work. It’s about understanding when chemistry isn’t enough—when site selection, species choice, seasonal timing, and maintenance matter more than perfect pH balance. Master both the science and the ecology, and you can grow art anywhere.