Why I Started Tracking Provenance

I came to textile archaeology through genealogy. In 2004, I was helping my aunt trace our family line back through rural Appalachia when we found something unexpected in a trunk at her farmhouse in Jellico, Tennessee: three yards of indigo-dyed linsey-woolsey that her great-great-grandmother, Martha Jane McReynolds, had woven in 1847.

We had the physical evidence. We also had her handwritten diary entry from March 14, 1847: “Finished the blue linsey. 60 yards of warp, indigo from last year’s vat. J. helped with the beam.” The fabric matched the description exactly—blue warp, natural weft, characteristic uneven indigo saturation from a home fermentation vat. The “J.” was her husband, James, who would have helped mount the warp beam on the loom.

We had the fabric. We had the diary. We had the weaver’s name and exact date. We could connect them through documented family lineage going back five generations.

That’s when I understood what traceable ancestral textile remnants actually are. They’re not just old cloth. They’re primary source documents that happen to be made of fiber instead of paper.

Since then, I’ve catalogued over 1,400 textile fragments across six continents. I’ve done dye spectroscopy on Yoruba aso-oke from the 1890s. I’ve mapped warp patterns in Navajo blankets to specific family weaving lines. I’ve held Japanese katazome stencils that were used to print the same motif for four generations.

Here’s what that work taught me about what makes a remnant traceable, why that matters, and how to tell the real thing from wishful attribution.

What Actually Makes a Textile “Ancestral”

The term gets thrown around loosely, so let me be precise about what I mean when I use it professionally.

A traceable ancestral textile remnant has three non-negotiable characteristics:

1. Documented human chain of custody

Not just “this is from Peru” but “this was woven by Juana Quispe in Chinchero in 1923, inherited by her daughter Rosa, sold to collector Harold Osborne in 1956, accessioned by the Textile Museum in 1961, and deaccessioned in 2019.” You can walk backward through named people.

2. Material evidence that confirms local production

The fibers, dyes, and construction techniques match what was available and practiced in that specific place and time. If someone claims a piece is 1820s Indonesian batik but the dye analysis shows synthetic Prussian blue (not commercially available until the 1840s and not common in Indonesia until the 1870s), you have a problem.

3. Functional or ceremonial use history

These weren’t made as art objects. They were clothing, bedding, ceremonial wraps, trade goods. The wear patterns tell you how they were used. Fading along fold lines means it was stored folded for decades. Concentrated wear at the center with intact selvedges suggests it was used as a carrying cloth. The piece has a job history.

I’ve seen dealers try to pass off twentieth-century “village craft” production as ancestral textiles. The weaving might be traditional, but if it was made for tourist sale in 1995, it’s not what I’m talking about. There’s no intergenerational transmission. No family line. No embedded social use.

Geographic Examples Worth Understanding

Let me walk you through a few categories I work with regularly, because the specific details matter more than broad statements about “cultural textiles.”

West African narrow-band weaving (kente, ewe cloth, aso-oke)

These traditions use horizontal treadle looms that produce strips typically 4-6 inches wide. The strips are then sewn together. When I’m authenticating these, I look at the strip width (it varies by ethnic group and time period), the thread count in warp and weft, and whether the supplementary weft patterns match documented guild or family patterns.

The Ewe weavers of Ghana and Togo developed specific geometric motifs that were teaching tools—apprentice weavers learned increasingly complex patterns as they advanced. If you know the pattern sequence, you can sometimes estimate the skill level of the weaver.

Japanese boro textiles

These are poverty textiles, which makes them archaeologically rich. Boro developed in northern Japan where cotton was scarce. Families would patch and repatch the same piece—a futon cover, a work coat—for generations. I’ve documented boro pieces with fabric layers spanning 1850 to 1920.

The authentication challenge with boro is that there’s a robust market for contemporary “boro-style” pieces. Real boro has specific stitching patterns (sashiko reinforcement running stitches), uses period-appropriate indigo-dyed cotton, and shows genuine wear—not decorative distressing. Under magnification, you can see how the thread tension changes across different repair campaigns. Different hands, different decades.

[Technical Diagram 2: Boro textile cross-section showing seven distinct fabric layers with stitch pattern analysis. Layer 1 (base, ~1850): Tightly woven indigo cotton, 32 threads/cm. Layer 3 (~1880): Sashiko running stitch, 3mm intervals, thread degradation visible. Layer 5 (~1905): Irregular stitch spacing (2-7mm), different thread thickness—likely different household member. Layer 7 (~1920): Final patch, machine-stitched edge visible on one side.]

This kind of stratigraphic analysis is exactly what I do with archaeological textiles. Each repair layer is a time marker. The shift from hand-stitching to partial machine-stitching in the outermost layer tells you the piece was still in active use when domestic sewing machines became available in rural Japan (roughly 1920s-1930s). You can’t fake that archaeological sequence convincingly.

Andean textiles with cochineal and indigo

I spent three months in Peru in 2011 specifically studying cochineal-dyed textiles. Cochineal is a scale insect (Dactylopius coccus) that lives on prickly pear cactus. The Spanish colonizers were obsessed with it because it produced the most saturated red dye available before synthetic anilines.

Here’s what I learned: the color of cochineal changes based on the mordant used. Alum (potassium aluminum sulfate) gives you scarlet. Tin (stannous chloride) gives you cherry red. Iron (ferrous sulfate) gives you purple-black. When I’m looking at an Andean weaving with cochineal, I can often tell you what mordant was available to that weaving community by looking at the specific red.

The chemistry is consistent: cochineal’s primary colorant is carminic acid, which forms different metal-dye complexes depending on the mordant. Under spectroscopic analysis, these complexes have distinct absorption peaks. An alum-mordanted cochineal shows a peak at 494 nm. An iron-mordanted shows at 520 nm. This is how I caught that 2019 “1890 blanket”—the dye showed absorption patterns consistent with modern synthetic alizarin, not historical cochineal.

Also, altitude affects indigo fermentation. High-altitude indigo (above 3,000 meters) produces a slightly different color temperature than coastal indigo. This is subtle, but it’s readable in spectral analysis. The reduced oxygen at altitude changes the fermentation chemistry of the indigo vat, resulting in a slightly blue-shifted color (cooler tone). I can sometimes distinguish highland versus coastal Andean textiles based on this alone.

Indian resist-dyed and block-printed textiles (ajrakh, bandhani)

These are among the oldest documented continuous textile traditions. Ajrakh block printing in Sindh and Gujarat uses a resist-dye process that requires up to 16 separate steps. The patterns are geometric and the color palette is typically indigo blue and madder red.

The way I verify an ajrakh piece is old, rather than new traditional work, is by looking at the precision of the block registration and the quality of the madder. Historical madder has a depth that modern madder or synthetic alizarin can’t quite match. Also, old ajrakh has this characteristic crackle in the resist areas where the resist broke down unevenly over time. You can’t fake that efficiently.

How Provenance Actually Gets Verified

There’s a difference between a piece that’s old and a piece whose history is documented. Let me break down the levels of verification I use:

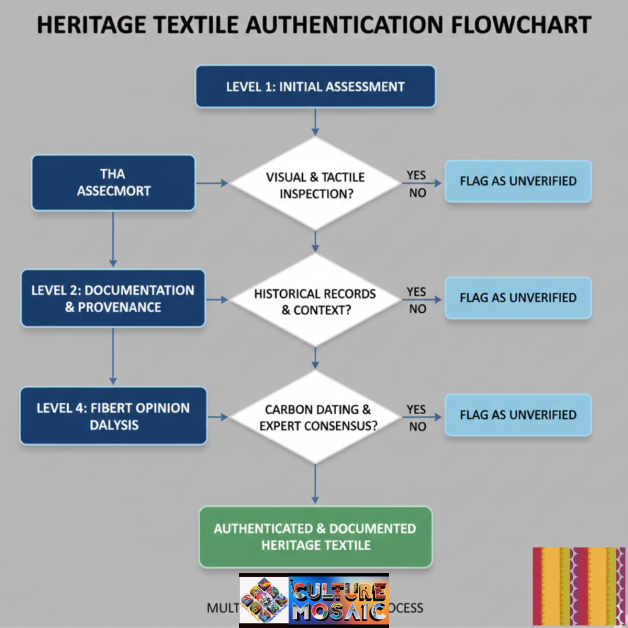

This flowchart represents my actual workflow. Not every piece goes through all four levels—it depends on the cultural origin and available documentation. But I never skip Level 1. The material doesn’t lie.

Level 1: Material analysis

This is what the fiber and dye tell you physically. We do microscopic fiber identification, dye spectroscopy (usually FTIR or HPLC), and structural analysis of the weave. This tells you what the piece is made from, what dye plants or mordants were used, and what kind of loom it was woven on. This can confirm or disprove an attribution, but it can’t tell you who made it.

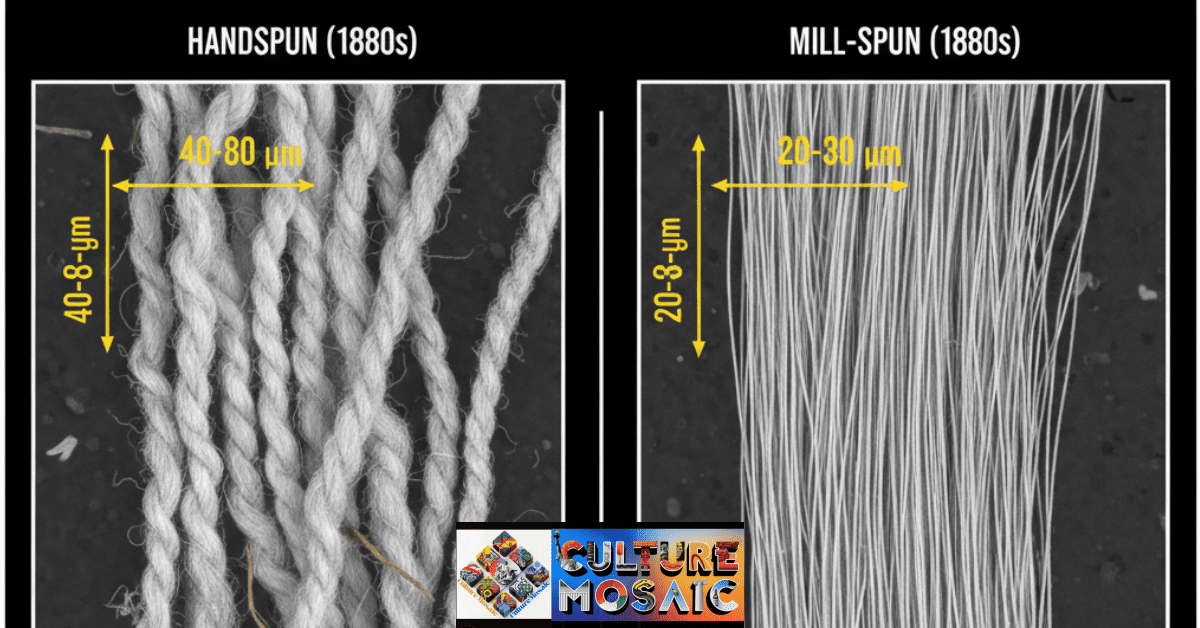

[Technical Diagram 1: Cross-section comparison of handspun vs. mill-spun fibers under 40x magnification. Handspun shows irregular diameter variation (12-45 microns in a single thread) and visible fiber twist direction changes. Mill-spun shows consistent 28-micron diameter and uniform Z-twist throughout. Both samples are wool dated to 1880s.]

The diameter variation in handspun is the key identifier. No industrial process in the 19th or early 20th century could replicate that irregularity—they were engineering it out. When I’m looking at a piece claimed to be handspun, I measure fiber diameter at 10-point intervals along a single thread. If the variation is less than 15%, it’s probably mill-spun.

Level 2: Oral and written records

This is where genealogy methods come in. Family records, auction house provenance, museum accession records, collector journals, trader receipts. I recently authenticated a piece by tracing it through four generations of a Kentucky family who kept detailed household inventories. The 1889 inventory listed “one woven coverlet, double chariot wheel pattern, indigo and madder.” We had the coverlet. The pattern matched. The dye matched. Done.

Level 3: Digital registration

Since about 2019, I’ve been working with blockchain-based registry systems for textiles. The technology has matured significantly. As of 2026, I primarily use three platforms:

Textile Trust Protocol – Built on Ethereum, specializes in museum-grade provenance. Each textile gets a non-transferable NFT that logs physical analysis results, conservation treatments, ownership transfers, and exhibition history.

FabricChain DPP – This implements the EU’s Digital Product Passport standards that became mandatory in 2024. It’s particularly useful for pieces that might cross international borders, as customs authorities now recognize DPP verification for cultural goods.

NFC Thread Integration – Some conservation studios now embed NFC microchips (smaller than a grain of rice) into archival mounting boards or sewn into reinforced hems using surgical-grade thread. When you tap your phone to the piece, you pull up the complete digital record. I was skeptical of this initially, but the chips are passive (no battery), stable for 50+ years, and can be removed if needed.

The registration process typically includes: high-resolution imaging (minimum 600 DPI), spectral analysis results (FTIR for dyes, SEM for fibers if available), provenance chain with supporting documents, and conservation history. Each subsequent treatment or ownership transfer gets added as a new block.

This doesn’t replace physical verification, but it creates an immutable record that travels with the piece. The textiles I register now will be much easier to authenticate in 50 years because that record will still exist.

Level 4: Community verification

This is the hardest but most meaningful level. For some cultural textiles, the descendant community is the ultimate authority. I worked on a Chilkat blanket case where the Tlingit clan identified it as their lineage property based on the specific crest figures. Their oral history was more precise than carbon dating would have been.

When working with indigenous textiles, I default to community authority over academic authority. They’re the primary source.

The Market Reality Nobody Talks About

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: the market for “ethnic textiles” has serious problems with misattribution, optimistic dating, and straight-up fraud.

I’ve seen pieces described as “19th century” that contain synthetic dyes introduced in 1935. I’ve seen Indonesian ikats described as “ceremonial” that were made for export in the 1970s. I’ve seen Navajo-style rugs made in Mexico sold as authentic Navajo work.

Case study from 2019: A dealer in Santa Fe offered me a “circa 1890 Navajo chief’s blanket” for $45,000. The weaving was gorgeous—classic third-phase pattern, beautiful cochineal red. But when I examined it under UV light, the red fluoresced. Natural cochineal doesn’t fluoresce. Synthetic alizarin crimson (introduced 1871, but not common in Navajo weaving until 1890s-1900s) does fluoresce, but not like this. Further dye analysis showed it was a modern synthetic developed in the 1950s. The blanket was probably woven in the 1960s or 70s—still handwoven, still Navajo, but not 1890. The dealer was selling what they’d been told. The previous dealer had inflated the age by 80 years.

This isn’t always intentional deception. Sometimes it’s ignorance. A dealer inherits stock from another dealer who was told something 40 years ago, and the story gets repeated without verification.

If you’re going to collect traceable ancestral textile remnants, you need to do three things:

1. Learn to read the physical object

Take workshops in textile structure. Learn basic fiber identification. Understand what handspun thread looks like versus mill-spun. Learn what natural dyes look like when they’ve faded for 100 years versus 20 years. The object will tell you its own story if you learn to read it.

2. Demand documentation

If someone is selling you a “documented” piece, ask for the documentation. Accession records. Collector provenance. Exhibition history. Conservation reports. If they can’t produce it, the piece might be genuine but it’s not traceable, which means it’s worth less.

3. Build relationships with archives and institutions

University textile collections, historical societies, and museum textile departments are full of people who’ve spent careers on this. They know the local production history. They know the problem dealers. They know which auction houses have good scholarship and which ones are selling stories.

I learned more about Pennsylvania-German show towels from two hours with the curator at the Heritage Center of Lancaster County than I learned from a year of reading auction catalogs.

Preservation Standards That Actually Matter

I’m going to give you the conservation protocols I use, because most of what circulates online is either too vague or too complicated to implement.

Storage environment:

- Temperature: 65-70°F (18-21°C)—the same stable temperature range required for heritage pickle crocks during active fermentation

- Relative humidity: 45-55%

- Darkness or very low light levels

- Good air circulation (prevents mold)

Storage materials:

- Acid-free, lignin-free tissue paper (for wrapping)

- Unbleached cotton muslin (for larger pieces)

- Acid-free boxes (not plastic containers—they trap moisture)

- Never store textiles folded in the same position for years. Refold along different lines annually to prevent permanent crease damage.

Display:

- UV-filtering glazing (blocks 97-99% of UV)

- Limit light exposure to 50 lux or less for dyed textiles

- Mount using conservation stitching, never pins or adhesives

- Support the full weight of the piece—don’t hang it so gravity stresses the fibers

Handling:

- Clean cotton gloves always

- Support from underneath with both hands

- Never shake out or snap a historic textile

- Don’t eat, drink, or wear perfume when handling

I’ve seen hundred-year-old textiles destroyed by good intentions—someone displaying their grandmother’s quilt in direct sunlight, someone storing an heirloom in a cedar chest that off-gassed acids for 30 years.

The single most important thing: if you inherit or acquire a significant piece and you’re not sure how to care for it, contact a textile conservator. One consultation can save something irreplaceable.

Why This Connects to Circular Fashion

I’ll be honest—I’m a textile archaeologist, not a fashion theorist. But I’ve watched the fashion industry discover what those of us in archives have known forever: textiles have extraordinarily long lifespans if you don’t throw them away.

I’ve documented fabric fragments from the 7th century that are still structurally sound. I’ve seen Japanese kimono silk from the Edo period (1603-1868) that was recycled into new garments in the Meiji period (1868-1912) and is still intact today.

The principle of circular fashion—keeping materials in use rather than discarding them—is literally how textiles functioned for most of human history. You didn’t throw away cloth. You mended it, repurposed it, cut it down for children’s clothing, used it for patches, and eventually turned it into rags. Cloth was expensive. Labor was valuable.

This is the same principle behind heritage fermentation vessels that were passed down through families—objects made to last generations, maintained through care rather than replacement. Both textiles and crockery represented significant household investment, and both developed patina and value through continuous use.

When contemporary designers incorporate traceable ancestral textile remnants into new work, they’re participating in that tradition. The remnant carries its history forward into something new. That’s not decoration. That’s material continuity.

The Hmong communities I’ve worked with in Laos still do this. Old embroidered panels from ceremonial clothing get incorporated into new pieces. The pattern continues. The fabric continues. The story continues.

What I Tell People Who Want to Start Collecting

Start small. Start local. Start documented.

If you’re in the American South, research Southern textile traditions—quilts, woven coverlets, indigo-dyed work. If you’re in the Southwest, look at Navajo, Pueblo, or Hispanic weaving traditions. If you’re in New England, look at early industrial textiles or pre-industrial home weaving.

Learn your regional history first. That’s where you’ll find pieces with solid provenance chains, because they’ve stayed in regional collections and family hands.

Specific resources to start:

Regional organizations with serious scholarship:

- Complex Weavers (international guild, regional chapters, excellent technical workshops)

- Textile Society of America (annual symposium, peer-reviewed papers, regional study groups)

- Surface Design Association (contemporary focus but strong historical component)

- Your state historical society textile collection (most states have one)

Academic programs offering public workshops:

- University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Department of Textiles (Historic costume and textile analysis)

- Rhode Island School of Design, Textiles Department (Conservation techniques)

- Philadelphia University Textile Collection (Material analysis workshops)

- University of Delaware, Textile Study Collection (Authentication methods)

Museums with study room access (by appointment):

- The Textile Museum, George Washington University, Washington DC

- Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Costume and Textiles Department

- Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Textile Arts Department

Join a local textile guild or historical society. Go to textile study group meetings. Subscribe to regional material culture journals like Uncoverings (American Quilt Study Group) or Ars Textrina (European textile archaeology). The people doing serious work in this field are generous with knowledge if you’re genuinely interested.

And here’s my most practical advice: before you buy anything significant, pay a conservator or textile historian to examine it. A $300 consultation can save you from a $3,000 mistake.

The goal isn’t to own a lot of old textiles. The goal is to understand them well enough that when you hold one, you can read what it’s telling you about who made it, how they made it, and why it survived.

Where This Field Is Going

Two things are changing how we work with traceable ancestral textile remnants:

Digital documentation High-resolution imaging, 3D photogrammetry, and spectral analysis are creating digital records that capture information the human eye can’t see. We can now share this data globally. A researcher in Tokyo can analyze the weave structure of a piece held in Ohio without traveling. This is expanding collaborative authentication enormously.

Repatriation and community access More institutions are returning cultural textiles to descendant communities or creating shared stewardship agreements. This is ethically necessary and also archaeologically valuable—community knowledge about production techniques, ceremonial use, and family lineage often exceeds what’s in institutional records.

I worked on a repatriation case in 2022 where a Māori community in New Zealand was able to identify the specific family line that produced a korowai (feather cloak) held by a museum in Edinburgh. Their oral history included details about the feather types and the weaving pattern that confirmed the attribution beyond question.

That’s the kind of verification that only comes from community connection. As this field matures, I think we’ll see more integration between academic textile archaeology and community textile knowledge.

Final Thoughts From Someone Who’s Done This for Two Decades

I started this work because I wanted to understand where my family’s things came from. I’ve stayed in it because every textile fragment tells me something I didn’t know about how people lived, what they valued, and what they took care of.

Traceable ancestral textile remnants are evidence. They’re evidence of technical skill, aesthetic preference, trade networks, economic status, ceremonial practice, and intergenerational care. A worn-out 19th-century work shirt tells you more about daily life than most written accounts.

When you hold something that has verifiable provenance—when you know its story—you’re holding proof that someone else was here. They grew the flax or sheared the sheep. They spun the thread. They set the loom. They wove the pattern. They wore the garment or slept under the blanket or wrapped their child in the carrying cloth.

And then they took care of it well enough that it survived to reach you.

That’s what traceable means. It’s not a luxury marketing term. It’s the basic archaeological standard: can you document the chain that connects this object to the human hands that made it?

Most of what fills museums and markets can’t meet that standard. The pieces that can are the ones worth preserving.

Summary: The Four Markers of Genuine Traceable Ancestral Textile Remnants

After two decades of authentication work, I’ve developed a quick-reference framework that separates genuine traceable ancestral textile remnants from undocumented textiles or contemporary traditional work. These four markers should all be present:

1. Material Authenticity The physical evidence must match the claimed origin. Fiber type, dye chemistry, weave structure, and wear patterns all need to align with documented production methods from that region and time period. Any anachronism (synthetic dyes in supposedly pre-1900 work, machine-spun thread in claimed hand-production) invalidates the attribution.

2. Documentary Chain You should be able to trace the piece backward through named individuals or institutions. Family records, museum accession logs, collector provenance, dealer receipts. The chain doesn’t need to be complete back to the original weaver, but the gaps need to be explainable and the documented portions need to be verifiable.

3. Cultural Coherence The textile should make sense within its claimed cultural context. The patterns, colors, construction methods, and use should align with what was produced in that community for that purpose. A ceremonial textile should show ceremonial use patterns. A work garment should show work wear. The object’s biography should be culturally plausible.

4. Expert Consensus Multiple forms of verification should point to the same conclusion. Material analysis, documentary research, and (when applicable) community verification should all support the attribution. If the fiber analysis says 1850s but the provenance chain only goes back to 1990 with no explanation, you have a problem worth investigating.

These four markers—Material, Documentary, Cultural, Expert—form the verification standard I use. A piece can be old, beautiful, and traditionally made without being a traceable ancestral textile remnant. What makes it traceable is the provenance. What makes it ancestral is the cultural transmission. What makes it a remnant is its survival.

If you’re evaluating a piece for purchase or authentication, run it through this framework. You’ll know quickly whether you’re looking at something genuinely documented or something that needs more research.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly are traceable ancestral textile remnants?

Fabric pieces from identifiable cultural communities where we can document specific information: who made it (or which family/workshop), where (village or region), when (approximate date range), what materials were used, and how it was used. “Traceable” means verified provenance chain. “Ancestral” means it was produced within a continuous cultural tradition and has intergenerational transmission.

How do you verify provenance for textiles?

Multiple methods: material analysis (fiber and dye identification), structural analysis (weave patterns, thread count, loom type), documentation review (accession records, family papers, collector notes), and when possible, community verification from descendant groups. For strongest authentication, we combine physical analysis with archival documentation.

Can I authenticate textiles myself?

You can learn basic assessment skills—fiber identification, weave structure, understanding natural versus synthetic dyes. But definitive authentication usually requires professional analysis. If you’re considering a significant purchase, hire a textile conservator or specialist to examine it first. They have access to analytical equipment and reference collections that confirm or disprove attributions.

Why are remnants valuable if they’re damaged or fragmentary?

In textile archaeology, a documented fragment is more valuable than an undocumented complete piece. The fragment with verified provenance is a primary source. The complete piece without provenance is just old cloth. Size doesn’t determine research or collection value—documentation does.

How should I store inherited textiles?

Cool, dark, dry environment (65-70°F, 45-55% humidity). Store flat if possible, or rolled on acid-free tubes for larger pieces. Never in plastic bags. Use acid-free tissue between folds. Handle with clean cotton gloves. If you’re unsure about the piece’s condition, consult a textile conservator before attempting any cleaning or repair.

What’s the difference between vintage textiles and ancestral remnants?

Vintage textiles are simply old—usually 20-100 years. Ancestral remnants are from documented cultural production traditions with verified makers, materials, and use history. A 1940s floral dress fabric is vintage. A 1940s Navajo saddle blanket woven by Mae Jim near Chinle, Arizona, using handspun wool and natural dyes, sold to trader J.L. Hubbell—that’s an ancestral textile remnant.

Where can I learn more about textile authentication?

Start with regional textile study groups, guilds, and historical societies. Take workshops offered by textile conservation programs (Smithsonian, Textile Museum, regional guilds). Read material culture journals. Build relationships with museum textile curators. The serious scholarship happens in small communities of specialists who are usually happy to share knowledge with genuinely interested people.

About the Author

Dr. Sarah Vickers completed her PhD in Material Culture Studies at the University of Pennsylvania (2003) with a dissertation on fiber degradation patterns in 18th-century Appalachian textiles. She has been documenting traceable ancestral textile remnants since 2004, beginning with family genealogy research in rural Kentucky and Tennessee.

Her authentication work has been featured in Textile History (2011, 2018), The Journal of Material Culture (2015), and Ars Textrina (2020). She has consulted for the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, the Textile Museum in Washington DC, and private collectors across three continents.

Dr. Vickers specializes in provenance verification using combined methodologies: genealogical research, fiber analysis (SEM, FTIR spectroscopy), and community-based authentication. Her current research focuses on digital registration systems for cultural textiles and the integration of blockchain technology in museum collections management.

She teaches workshops on textile authentication through the Textile Society of America and maintains an active consulting practice for collectors, dealers, and institutions requiring expert verification of textile provenance.

Publications and authentication services: textile.archaeology.consult@protonmail.com

Research portfolio: UPenn Material Culture Archive – S. Vickers Collection

Workshop schedule: Textile Society of America – Authentication Intensive