Indigenous Foodways: The quiet revolution happening in kitchens, farms, and community centers across America isn’t being led by celebrity chefs or venture-backed startups. It is guided by the knowledge keepers of Indigenous nations, who have never forgotten what the land has always known: that food is medicine, culture is survival, and our plates hold the power to heal both people and the planet.

Indigenous foodways—the traditional food systems, agricultural practices, and culinary wisdom of Native peoples—are experiencing a profound renaissance. What mainstream culture is only now discovering as “superfoods” and “regenerative agriculture” has been practiced for millennia by Indigenous communities. This isn’t a trend. It’s a reclamation, a revival, and for many, an act of cultural sovereignty.

What Are Indigenous Foodways?

Indigenous foodways encompass far more than recipes or ingredients. They represent complete food systems that include:

- Traditional agricultural practices passed down through generations

- Seed saving and biodiversity preservation that maintains genetic diversity

- Seasonal harvesting methods aligned with natural cycles

- Food preparation techniques that maximize nutrition and minimize waste

- Spiritual and ceremonial relationships with food

- Community-based food sharing and distribution systems

- Land stewardship practices that regenerate ecosystems

These foodways developed over thousands of years, creating perfectly adapted relationships between people, plants, animals, and landscapes. They’re not relics of the past—they’re living, evolving systems that hold answers to our most pressing contemporary challenges: climate change, food insecurity, nutrition-related diseases, and cultural disconnection.

The Wisdom Behind Indigenous Foodways

When we talk about Indigenous foodways, we’re discussing sophisticated food systems that Western science is only beginning to understand and validate.

The Three Sisters: Ancient Companion Planting

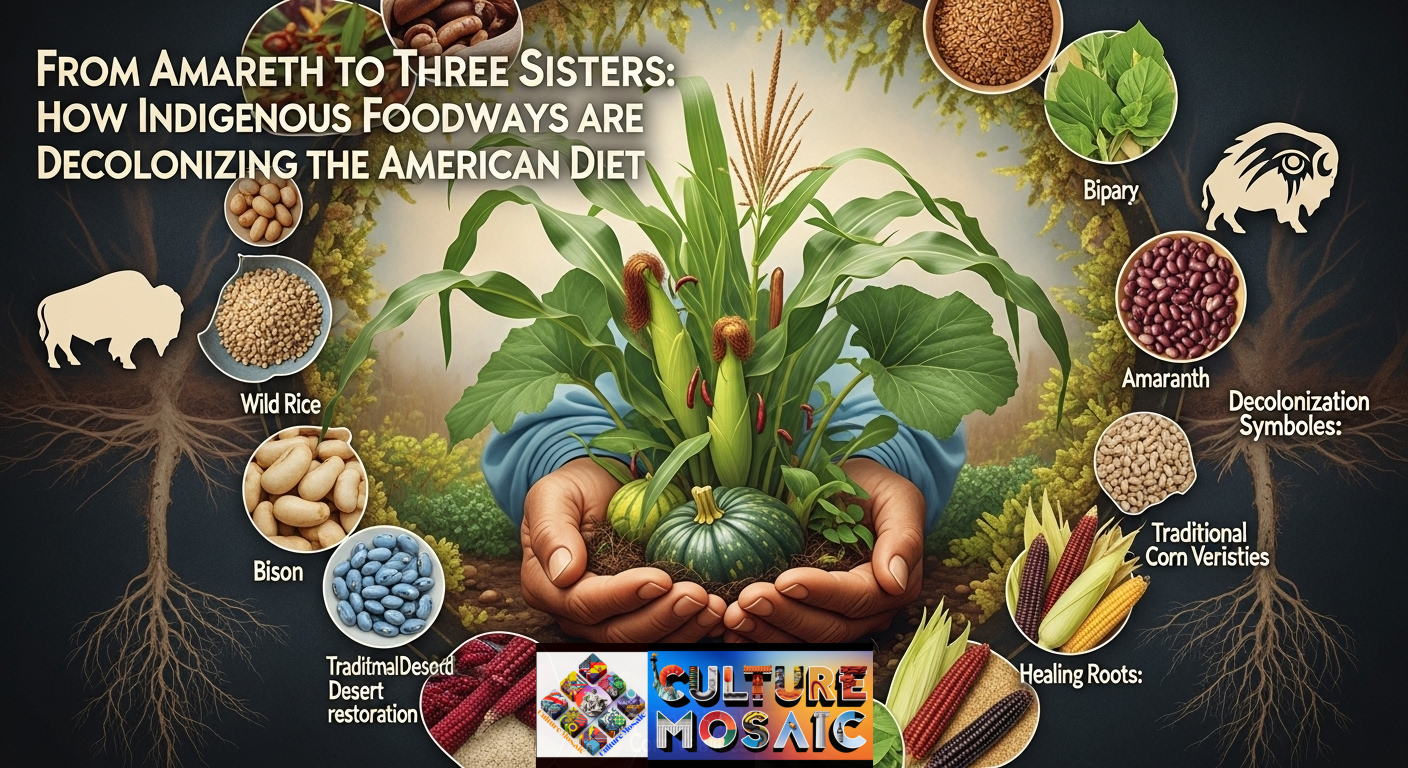

Perhaps the most famous example of Indigenous agricultural wisdom is the Three Sisters—corn, beans, and squash—grown together by many Native American nations. This isn’t just companion planting; it’s a masterclass in ecological design.

The corn provides a natural trellis for climbing beans. The beans fix nitrogen in the soil, which in turn feeds the corn and squash. The squash leaves create ground cover that retains moisture and prevents weeds. Together, they create a complete protein and provide balanced nutrition. This system has been refined over thousands of years, creating yields that rival or exceed modern monoculture farming—without synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, or the soil degradation that comes with industrial agriculture.

Food as Medicine

Indigenous foodways have always understood what nutritional science is now confirming: food is our first medicine. Traditional diets emphasized:

- Whole, unprocessed foods in their natural forms

- Seasonal eating that provides varied nutrients throughout the year

- Fermentation and preservation that enhance nutritional value and gut health

- Wild foods and foraged ingredients with concentrated phytonutrients

- Medicinal plants integrated into daily meals

The traditional Native American diet, which varied by region but included foods like wild rice, salmon, bison, acorns, wild berries, and amaranth, was remarkably nutrient-dense and led to low rates of diabetes, heart disease, and obesity—conditions that became epidemic in Native communities only after displacement from traditional lands and forced adoption of processed Western diets.

Biodiversity as Insurance

Indigenous farmers understood that diversity equals resilience. Rather than planting single varieties (monocultures), traditional Indigenous agriculture cultivated numerous varieties of each crop, ensuring that if one failed due to drought, pests, or disease, others would survive.

The Inca civilization, for example, cultivated over 4,000 varieties of potatoes, each adapted to specific microclimates and conditions. Many Southwestern Native nations maintained dozens of corn varieties, each with specific uses and environmental adaptations. This biodiversity wasn’t accidental—it was intentional preservation of food security across generations.

The Indigenous Foodways Summit: Gathering Knowledge Keepers

The Indigenous Foodways Summit represents a crucial gathering space where traditional knowledge meets contemporary challenges. These summits, held in various locations and sometimes virtually, bring together Indigenous farmers, chefs, activists, educators, and youth to share knowledge, coordinate efforts, and strengthen the ancestral food revival movement.

What Happens at an Indigenous Foodways Summit

These gatherings typically include:

- Seed exchanges, where participants share traditional crop varieties

- Cooking demonstrations featuring ancestral ingredients and techniques

- Land-based teachings about traditional harvesting and agriculture

- Youth programming to pass knowledge to the next generation

- Policy discussions addressing food sovereignty and land rights

- Storytelling circles connecting food with cultural identity

- Market opportunities for Indigenous food producers

The summits serve multiple purposes: they’re educational forums, political organizing spaces, cultural celebrations, and business development opportunities all rolled into one. They create networks that extend beyond the event itself, fostering ongoing collaboration and knowledge sharing.

Key Themes from Recent Summits

Recent Indigenous foodways summits have centered around several critical themes:

Food Sovereignty: The right of peoples to healthy, culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.

Climate Resilience: How traditional Indigenous agricultural practices offer proven solutions for climate adaptation, including water conservation, soil regeneration, and drought-resistant crops.

Decolonizing the Food System: Examining how colonial food policies continue to impact Indigenous communities and working toward systems that honor traditional practices and land relationships.

Intertribal Collaboration: Building bridges between different Indigenous nations to share knowledge, resources, and support for food system revitalization.

The Ancestral Food Revival Movement: More Than a Trend

What’s being called the ancestral food revival is fundamentally about cultural survival and healing. For Indigenous communities, revitalizing traditional foodways isn’t about nostalgia—it’s about health, sovereignty, and resistance to ongoing colonization.

The Health Crisis and Food Connection

Native American communities face disproportionately high rates of diabetes, with some communities experiencing rates five times higher than the national average. Heart disease, obesity, and other diet-related illnesses are epidemic. This wasn’t always the case.

The shift happened through forced displacement from traditional lands, disruption of hunting and gathering practices, government commodity food programs that provided processed foods high in sugar and fat, and systematic destruction of traditional food systems through boarding schools and assimilation policies.

The ancestral food revival directly addresses this health crisis. Studies show that when Native people return to traditional diets, health improvements are dramatic. A Tohono O’odham community member who switched to a traditional diet showed reversal of Type 2 diabetes within months. Traditional foods are so powerful that they’re now being prescribed as medicine in some tribal health programs.

Cultural Reconnection Through Food

For many Indigenous people, especially younger generations removed from traditional practices through historical trauma and urbanization, food offers a tangible entry point to cultural reconnection.

Learning to prepare traditional foods, growing ancestral crops, or participating in seasonal harvests creates embodied connections to culture that history books cannot provide. Food carries stories, languages, songs, and ceremonies. When a grandmother teaches her granddaughter to make frybread or traditionally prepare salmon, she’s transmitting far more than a recipe—she’s passing on cultural identity, resilience, and love.

Economic Development and Food Sovereignty

The ancestral food revival is also creating economic opportunities in Indigenous communities. Native-owned food businesses are growing, from restaurants serving traditional cuisine to farms producing heritage crops to value-added products like teas, seasonings, and preserved foods.

These businesses do more than generate income—they create dignified employment in communities with high unemployment rates, they keep wealth circulating within the community, and they provide alternatives to the exploitative food system that currently dominates reservations and Indigenous communities.

Examples include:

- The Sioux Chef (Owamni restaurant in Minneapolis) serves decolonized pre-colonial Indigenous cuisine

- Tanka Bar, making buffalo meat snacks

- Traditional Native American Farmers Association supports Native farmers across the Southwest

- Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance is coordinating food system development across Indian Country

- Countless tribal food enterprises, community gardens, and seed-saving initiatives

The New Superfoods Are Centuries Old: Rediscovering Indigenous Ingredients

While the wellness industry constantly seeks the next exotic superfood (often appropriating Indigenous knowledge in the process), Native communities have been cultivating nutritional powerhouses for millennia.

Amaranth: The Aztec Grain That Refused to Die

Indigenous Foodways: Amaranth, a pseudo-grain cultivated by the Aztec civilization, was banned by Spanish conquistadors because of its use in religious ceremonies. Despite centuries of suppression, it survived in small pockets and is now experiencing a renaissance.

This tiny seed is a complete protein, containing all essential amino acids—rare for a plant food. It’s high in lysine, an amino acid lacking in most grains, and provides significant calcium, iron, magnesium, and phosphorus. It’s also naturally gluten-free and grows well in marginal soils with little water, making it ideal for climate adaptation.

Wild Rice: The Sacred Grain

Wild rice (manoomin in Anishinaabe) is not actually rice but the seed of an aquatic grass native to the Great Lakes region. For the Anishinaabe people, wild rice is sacred, central to both diet and spiritual life. Harvesting wild rice is a ceremony as much as a food-gathering activity.

Nutritionally, wild rice outperforms white rice in nearly every category: higher protein, more fiber, richer in B vitamins and minerals, and a lower glycemic index. It’s also packed with antioxidants. Traditional hand-harvested wild rice from natural lakes tastes remarkably different from cultivated paddy rice—nuttier, more complex, and deeply satisfying.

Tepary Beans: Desert Survivors

Tepary beans, cultivated by O’odham and other Southwestern peoples for thousands of years, are perfectly adapted to desert conditions. They need minimal water and thrive in heat that would kill other bean varieties.

These small beans have a lower glycemic index than most legumes, making them particularly beneficial for diabetes management. They’re high in protein and fiber, and their unique composition makes them easier to digest than many other beans. Research suggests that tepary beans may actually help regulate blood sugar and support pancreatic function.

Bison: The Original Regenerative Livestock

Before cattle, 30-60 million bison roamed North America, creating and maintaining the prairie ecosystem through their grazing patterns. Their relationship with the land was regenerative—they moved frequently, their hooves aerated soil, their grazing stimulated plant growth, and their waste fertilized grasslands.

Bison meat is leaner than beef, higher in omega-3 fatty acids, and raised bison require no grain finishing—they thrive on grass alone. For Plains nations, bison wasn’t just food; every part of the animal was used, and the relationship was sacred. The near-extinction of bison was a deliberate colonial strategy to destroy Indigenous food systems and force dependence on the US government.

Today, efforts to restore bison to tribal lands represent both ecological restoration and cultural revitalization. The InterTribal Buffalo Council supports 82 tribes in managing buffalo herds, reconnecting communities with this sacred relative.

Traditional Corn Varieties: Genetic Treasures

Modern industrial corn—whether the sweet corn we eat fresh or the field corn used for processed foods—represents a tiny fraction of corn’s genetic diversity. Traditional Native corn varieties number in the hundreds, each adapted to specific regions and uses.

These heritage varieties offer drought resistance, pest resistance, and nutritional profiles that commercial varieties lack. Many traditional corns have higher protein content, better mineral profiles, and more complex carbohydrates than modern hybrids. Some varieties are specifically adapted for dry farming, producing crops without irrigation in places where commercial corn would fail.

Organizations like Native Seeds/SEARCH work to preserve and distribute these varieties, ensuring that this irreplaceable genetic diversity isn’t lost.

Indigenous Foodways Around the World: Global Perspectives

Indigenous Foodways: While this article focuses primarily on Native American foodways, the ancestral food revival is a global phenomenon, with similar movements among Indigenous peoples worldwide.

The Andean Food System: Engineering at Altitude

The Andes mountains of South America host some of the world’s most sophisticated traditional agriculture. Inca and pre-Inca civilizations engineered agricultural systems that fed millions in one of Earth’s most challenging environments.

Potato Diversity: The Andes are the birthplace of the potato, where Indigenous communities still maintain thousands of varieties, each with specific uses and environmental tolerances. Some grow at altitudes where few other crops survive; others resist frost or store for years.

Quinoa: This protein-rich pseudo-grain, sacred to Andean peoples, grows at high altitudes where wheat and rice cannot. Like amaranth, it’s a complete protein and highly nutritious. Its recent popularity has created both opportunities and challenges for Indigenous Andean communities.

Terracing and Water Management: Ancient terrace systems and irrigation channels, some still in use today, demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of water flow, microclimate creation, and erosion prevention.

West African Foodways: The Seeds That Crossed Oceans

West African food systems gave the world many staple crops and farming techniques. During the transatlantic slave trade, enslaved Africans brought seeds, knowledge, and foodways that profoundly shaped American cuisine, particularly in the South.

African Rice: African rice (Oryza glaberrima) was independently domesticated in West Africa. Enslaved West Africans, particularly women, carried rice seeds in their hair and recreated rice-growing systems in the Carolina Lowcountry, creating the foundation for colonial rice wealth—knowledge and labor that was never compensated.

Yams: True yams (different from American sweet potatoes often called yams) are central to West African foodways. Dozens of varieties exist, each with particular characteristics and uses.

Okra, Black-eyed Peas, and Watermelon: These now-American staples all have West African origins, brought through the slave trade along with the knowledge of how to grow and prepare them.

Pacific Islander Foodways: Navigating by Food

Pacific Islander communities developed incredible food systems adapted to island living, including sophisticated aquaculture, agroforestry, and breadfruit cultivation.

The revival of traditional Pacific Islander foodways addresses health crises similar to those in Native American communities, where introduced processed foods have displaced traditional diets with devastating health consequences.

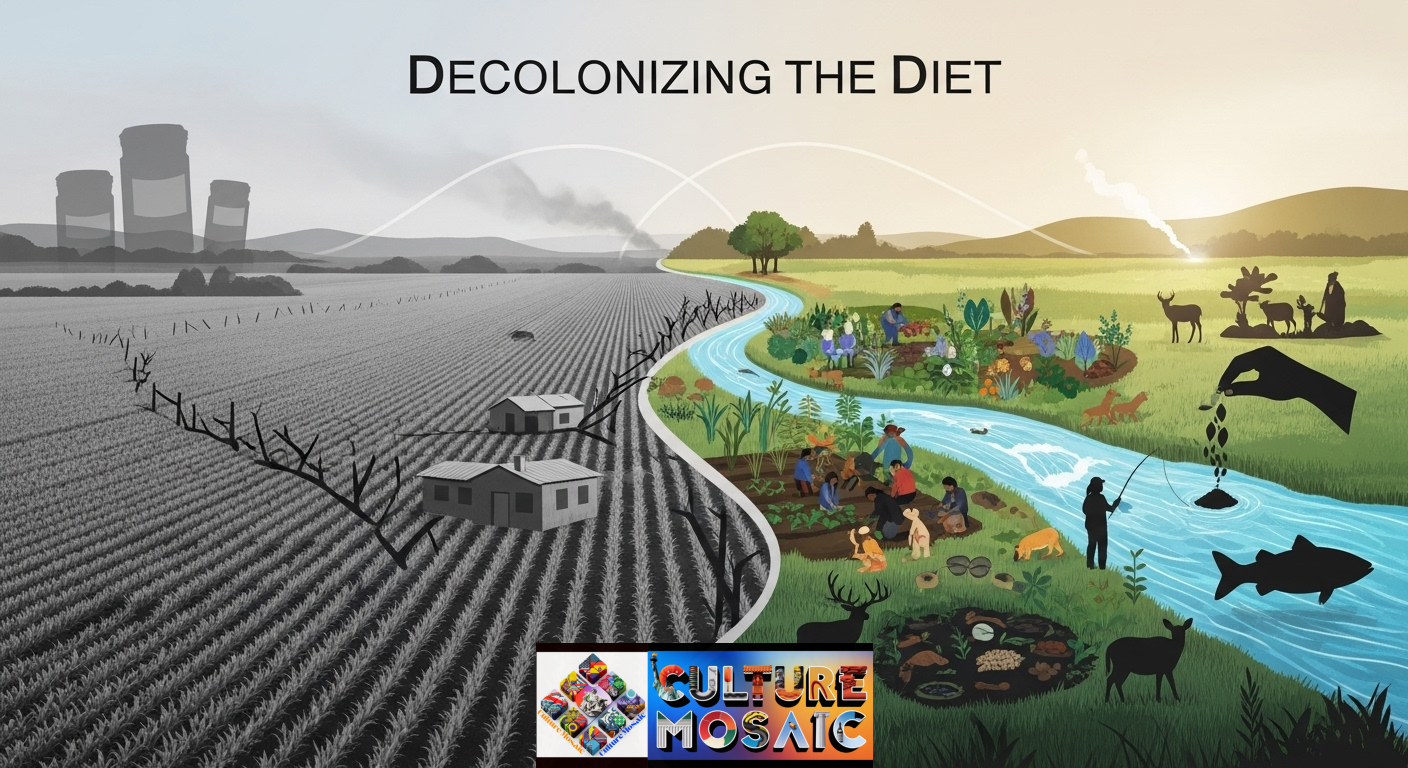

Decolonizing the Diet: What It Really Means

“Decolonizing the diet” has become a popular phrase, but its true meaning is often misunderstood. This isn’t about culinary tourism or adding exotic ingredients to your shopping list—it’s about recognizing and resisting the ongoing impacts of colonization on food systems.

Understanding Food Colonization

Food colonization involves:

- Land theft that removed Indigenous peoples from their traditional food sources

- Forced relocation to lands unsuitable for traditional practices

- Commodity food programs that created dependence on processed, unhealthy foods

- Boarding schools that deliberately disrupted food knowledge transmission

- Fishing and hunting restrictions that criminalized traditional food gathering

- Government agriculture policies that promoted industrial farming over traditional practices

- Cultural suppression that made traditional foodways seem inferior or “primitive”

These aren’t historical issues—they’re ongoing. Native communities still face restrictions on traditional fishing and hunting. Food deserts on reservations make accessing fresh, healthy food difficult. Government commodity programs still provide highly processed foods.

Personal Decolonization

For individuals, particularly Indigenous people, decolonizing your diet might mean:

- Learning traditional food preparation methods

- Growing or foraging ancestral foods

- Reducing reliance on processed, industrial foods

- Reconnecting with seasonal eating patterns

- Understanding the history of foods in your region

- Supporting Indigenous food producers

- Participating in traditional food gathering or ceremonies

For non-Native people, decolonizing your approach to food means:

- Learning whose land you’re on and what traditional foods grew there

- Supporting Indigenous food sovereignty movements

- Purchasing from Indigenous food producers when possible

- Resisting appropriation of Indigenous foods and knowledge

- Advocating for Indigenous land rights and water rights

- Examining how colonial food systems benefit you

- Respecting that some foods and practices are not for non-Native participation

How to Support the Indigenous Food Revival

Indigenous Foodways: Whether you’re Indigenous or not, there are meaningful ways to support ancestral food revival efforts.

Support Indigenous-Owned Food Businesses

Seek out and purchase from Native-owned restaurants, food producers, and farmers. This includes:

- Restaurants serving traditional Indigenous cuisine

- Native-produced items like wild rice, bison, traditional teas, and preserved foods

- Indigenous farmers’ markets and food co-ops

- Seed companies preserving and distributing traditional varieties

When you purchase these foods, you’re directly supporting Indigenous economic development, cultural preservation, and food sovereignty.

Learn the Food History of Your Region

Every place in North America has an Indigenous food history. Research:

- Which Indigenous nations are the original stewards of the land where you live

- What foods were traditionally grown, gathered, or hunted in your area

- Whether any traditional foods are still available locally

- How colonization affected local Indigenous food systems

This knowledge creates context and respect for the land you inhabit and the people who cared for it long before you arrived.

Advocate for Food Sovereignty

Support policies and initiatives that strengthen Indigenous food sovereignty:

- Land back movements that return land to Indigenous stewardship

- Tribal food system funding and support

- Protections for traditional fishing and hunting rights

- Seed sovereignty and protection of traditional varieties

- Clean water initiatives (essential for Indigenous food systems)

- Indigenous-led conservation and land management

Grow Traditional Varieties

If you garden, consider growing traditional Native varieties of crops appropriate to your region. Organizations like Native Seeds/SEARCH, Seedsavers Exchange, and various tribal seed programs offer traditional varieties.

Growing these seeds keeps them alive and viable, helping prevent genetic erosion. However, approach this respectfully—some seeds are sacred and not appropriate for non-Native cultivation. Always research the cultural context.

Respect Cultural Boundaries

Not all Indigenous food knowledge is meant to be shared outside communities. Some foods, preparation methods, and practices are sacred or ceremonial. Some knowledge is proprietary and belongs to specific families or nations.

Appreciation means respecting boundaries. Support Indigenous food sovereignty without appropriating practices that aren’t offered for sharing. Follow Indigenous leaders and educators to learn what’s appropriate and what isn’t.

The Future of Indigenous Foodways

The ancestral food revival is gaining momentum, driven by Indigenous youth reconnecting with their heritage, elders sharing knowledge before it’s lost, and growing recognition that traditional foodways offer solutions to modern crises.

Youth Leadership

Young Indigenous people are increasingly leading food sovereignty efforts, bringing fresh energy and perspectives while honoring traditional knowledge. They’re creating innovative projects that blend ancestral wisdom with contemporary approaches:

- Youth seed-saving initiatives

- Traditional food cooking programs

- Indigenous food TikTok and Instagram accounts are making traditional foodways accessible

- Youth councils guiding tribal food policy

- Student-led community gardens on tribal lands

Climate Solutions

As climate change accelerates, Indigenous foodways offer proven adaptation strategies. Traditional practices like dry farming, crop diversity, seasonal rotation, and land-based water management are being recognized as climate solutions that can work at scale.

Indigenous communities are often at the forefront of climate impacts, yet they hold knowledge that could help everyone adapt. Supporting Indigenous food sovereignty is supporting climate resilience.

Healing Generations

Perhaps most importantly, the food revival is healing intergenerational trauma. When families cook together using traditional methods, when children learn to plant their ancestors’ seeds, when communities gather for traditional harvests—healing happens. Food becomes the medium through which cultural continuity is restored and pride is reclaimed.

Conclusion: Indigenous Foodways, Food Is Resistance, Food Is Healing

Indigenous foodways represent far more than diet choices or agricultural techniques. They embody relationships—to land, to community, to ancestors, and to future generations. In every seed planted, every traditional meal prepared, every young person learning ancestral food knowledge, resistance, and revitalization are happening simultaneously.

The ancestral food revival isn’t asking permission from the dominant culture. It’s not waiting for validation from nutrition science or approval from the wellness industry. It’s Indigenous peoples reclaiming what was never fully lost, healing what was damaged, and asserting sovereignty over one of life’s most fundamental aspects: food.

For those outside Indigenous communities, this movement offers lessons about sustainability, health, and our relationship with the natural world. But more than that, it challenges us to examine how we benefit from ongoing colonization and what responsibility we have to support Indigenous sovereignty in all its forms.

The seeds have always held the knowledge. The land remembers the old ways. The wisdom never disappeared—it was just waiting for the right moment to flourish again. That moment is now.

Frequently Asked Questions About Indigenous Foodways

What are Indigenous foodways, and why are they important?

Indigenous foodways are the traditional food systems, agricultural practices, and culinary knowledge developed by Native peoples over thousands of years. They’re important because they represent sustainable food systems that support human health, environmental health, and cultural survival. These foodways offer solutions to modern challenges like climate change, nutrition-related diseases, and biodiversity loss while preserving irreplaceable cultural knowledge.

How can non-Native people support Indigenous food sovereignty respectfully?

Non-Native people can support Indigenous food sovereignty by purchasing from Indigenous-owned food businesses, advocating for Indigenous land rights and water rights, learning about the Indigenous food history of their region, respecting cultural boundaries around sacred foods and practices, and amplifying Indigenous voices in food and environmental discussions rather than speaking over them.

What is the difference between cultural appreciation and appropriation of Indigenous foods?

Cultural appreciation involves supporting Indigenous food businesses, respecting cultural boundaries, crediting Indigenous origins of foods and knowledge, and following Indigenous leadership. Appropriation involves taking Indigenous knowledge or foods for profit without credit or compensation, treating sacred foods as trendy commodities, speaking as an authority on Indigenous foods without proper knowledge or permission, or using Indigenous culture as marketing without supporting actual Indigenous communities.

What happened at the Indigenous Foodways Summit?

Indigenous Foodways Summits bring together Native farmers, chefs, educators, and community members to share traditional knowledge, coordinate food sovereignty efforts, exchange seeds, demonstrate traditional cooking techniques, discuss policy issues, and strengthen networks for ancestral food revival. These summits serve as crucial spaces for cultural transmission, political organizing, and community building around food system revitalization.

How do traditional Indigenous diets improve health outcomes?

Traditional Indigenous diets—emphasizing whole, unprocessed foods like wild rice, salmon, bison, traditional beans, and vegetables—are nutrient-dense and naturally balanced. Studies show that returning to traditional diets can reverse Type 2 diabetes, improve heart health, support a healthy weight, and reduce chronic disease rates. These foods have lower glycemic indexes, higher nutrient density, and better fatty acid profiles than processed Western foods that have become common in many Native communities.