Museums have long been viewed as guardians of world culture, but a growing number of people are questioning who gave them that authority in the first place. The repatriation movement—the process of returning cultural objects, human remains, and sacred artifacts to their countries or communities of origin—has moved from academic circles to the mainstream, driven largely by young activists using social media to expose the colonial roots of major museum collections.

This isn’t just about old objects gathering dust in display cases. It’s about identity, justice, and the right of communities to reclaim their own stories.

What Is Repatriation and Why Does It Matter?

Repatriation refers to the return of cultural property, human remains, or sacred items to their place of origin or to the descendants of the communities that originally produced them. While the term can apply to various contexts, including the return of refugees to their home countries, in the heritage world, it specifically addresses objects taken during periods of colonization, military conflict, or unethical archaeological excavations.

The stakes are high. We’re talking about ancestral remains removed from burial sites, religious objects still considered sacred by living communities, and artwork looted during colonial conquest. For many Indigenous peoples, African nations, and other affected communities, these aren’t historical curiosities. They’re living connections to ancestors and cultural practices that continue today.

The conversation around repatriation has exploded in recent years, particularly in the United States, where both international and domestic cases have captured public attention. Museums that once insisted their collections were “universal” are now being forced to reckon with uncomfortable truths about how they acquired their most prized possessions.

The Digital Generation Demanding Ancestral Justice

Suppose you’ve scrolled through TikTok or Instagram lately. In that case, you’ve probably seen it: young creators standing in museum galleries, pointing at objects with captions like “Let me tell you how this got here” or using the hashtag #StolenHeritage. These aren’t professional historians or archaeologists. They’re Gen Z activists who’ve decided that the traditional museum narrative needs an urgent rewrite.

This digital activism has proven remarkably effective. A single viral video can reach millions of people, many of whom had never considered how their local museum acquired its Egyptian mummies or West African masks. The algorithm favors controversy, and repatriation debates deliver plenty of it.

Unlike previous generations who might have organized physical protests or written letters to museum boards, today’s activists are creating educational content that’s both entertaining and damning. They’re using humor, music, and quick cuts to make the case that keeping looted objects is indefensible. Museums, accustomed to controlling their own narratives through carefully worded wall text, are finding themselves outmaneuvered by 60-second videos.

The impact extends beyond awareness. Several museums have cited public pressure, including social media campaigns, as factors in their decisions to begin repatriation processes. When the conversation happens in public, on platforms where museums are trying to attract younger visitors, institutions can no longer simply wait for the controversy to fade.

NAGPRA: The US Repatriation Law That Changed Everything

While international repatriation cases often make headlines, the United States has been dealing with these issues on its own soil for decades through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, known as NAGPRA.

Passed in 1990, NAGPRA requires museums and federal agencies to return Native American cultural items, including human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated tribes. It was groundbreaking legislation, recognizing that Native American communities have rights to their ancestors and cultural property that supersede the interests of museums and researchers.

The reality of NAGPRA implementation has been complicated. As of recent years, thousands of institutions still hold Native American remains and objects that should have been returned. Some museums have been excellent partners in the repatriation process. Others have dragged their feet, citing lack of funding, unclear cultural affiliation, or the need for additional study.

Recent updates to NAGPRA regulations have strengthened the law, making it clear that museums cannot retain Native American human remains simply because they want to study them. The new rules also address the disposition of culturally unidentifiable remains, requiring consultation with tribes rather than allowing museums to make unilateral decisions.

For Native American communities, NAGPRA represents more than legal compliance. It’s about healing historical trauma and restoring relationships between the living and their ancestors. When remains are returned and reburied according to traditional practices, it’s a form of justice that can’t be measured in policy papers.

From Universal Museums to Cultural Reckoning

Major institutions like the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian Institution have long operated under what’s called the “universal museum” principle. The idea is that these encyclopedic collections serve humanity by preserving and displaying cultural treasures from around the world, making them accessible to global audiences.

It’s a nice theory. The problem is that it conveniently ignores how those collections were assembled.

The Parthenon Sculptures, also called the Elgin Marbles, were removed from Athens in the early 1800s by a British diplomat who claimed he had permission from Ottoman authorities who were occupying Greece at the time. Greece has been requesting their return for decades. The British Museum’s response has essentially been: we’re taking better care of them than you would.

The Benin Bronzes represent another glaring example. These intricate plaques and sculptures were looted by British forces during an 1897 military expedition in present-day Nigeria. Thousands of objects were dispersed to museums worldwide, with Nigeria left with almost none of its own artistic heritage. After years of campaigning, several institutions, including the Smithsonian, have committed to returning their Benin Bronzes.

American museums are facing similar reckonings. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has returned artifacts to countries including Egypt, Italy, and Cambodia after investigations revealed they had been looted or illegally exported. These aren’t isolated cases—they’re symptoms of a collecting culture that prioritized acquisition over ethics for generations.

The universal museum argument is crumbling because it’s fundamentally paternalistic. It assumes that Western institutions are better stewards of other people’s heritage than those people themselves, which is hard to defend in 2025.

Living Heritage: Objects That Still Have Spiritual Power

One of the most important shifts in the repatriation conversation is understanding that many of these objects aren’t just art or artifacts. For the communities they came from, they’re living heritage with ongoing cultural and spiritual significance.

Take Hopi sacred objects, for example. These items were created for specific ceremonial purposes within a complex religious system. They weren’t meant to be seen by outsiders, let alone displayed under museum lights. When they’re held in museums, it’s not just a matter of physical possession—it disrupts spiritual practices that have continued for centuries.

The same applies to African power objects, Aboriginal Australian tjurunga, and countless other items that were collected with little regard for their sacred status. Researchers and collectors often viewed these objects through a purely aesthetic or anthropological lens, ignoring or dismissing the religious beliefs of the people who made them.

Repatriation allows these objects to return to their proper context, where they can continue to serve their intended purpose. Some items are returned to active ceremonial use. Others are cared for by community cultural centers where access is controlled according to traditional protocols. The key is that the source community makes these decisions, not distant curators.

This perspective challenges the museum model itself. If an object’s primary value comes from its role in living cultural practice rather than its display value, what’s a museum’s justification for keeping it? The question makes many institutions uncomfortable, which is exactly why it needs to be asked.

Digital Repatriation: Progress or Poor Substitute?

Not every object can or will be physically returned. Some items are too fragile to travel. Others are scattered across dozens of institutions worldwide. Still others exist in legal gray zones where ownership is disputed or unclear.

Enter digital repatriation—the practice of creating high-quality digital records, 3D scans, and virtual reality experiences of cultural objects and making them accessible to source communities. Several museums and archives have embraced this approach, arguing it democratizes access while preserving physical objects.

The Smithsonian Institution has digitized millions of items, including many Native American objects, and made them available through online databases. Some tribal communities have used these digital records to reconnect with traditional art forms and manufacturing techniques that had been lost or suppressed during periods of cultural erasure.

But digital repatriation is controversial. Critics argue it’s a way for museums to appear progressive while maintaining control over physical objects. A 3D model of a sacred mask isn’t the same as the mask itself, especially if that object is meant to be used in ceremonies or maintained according to traditional protocols.

There’s also the question of who controls these digital assets. If a museum creates a high-resolution scan of a ceremonial object and then restricts how that digital file can be used, is that really repatriation? Or is it just another form of possession dressed up in modern technology?

Some communities have embraced digital repatriation as a valuable tool, especially when physical return isn’t possible. Others view it as an inadequate compromise that allows museums to avoid harder questions about ownership and justice. The truth probably lies somewhere in between, varying from case to case.

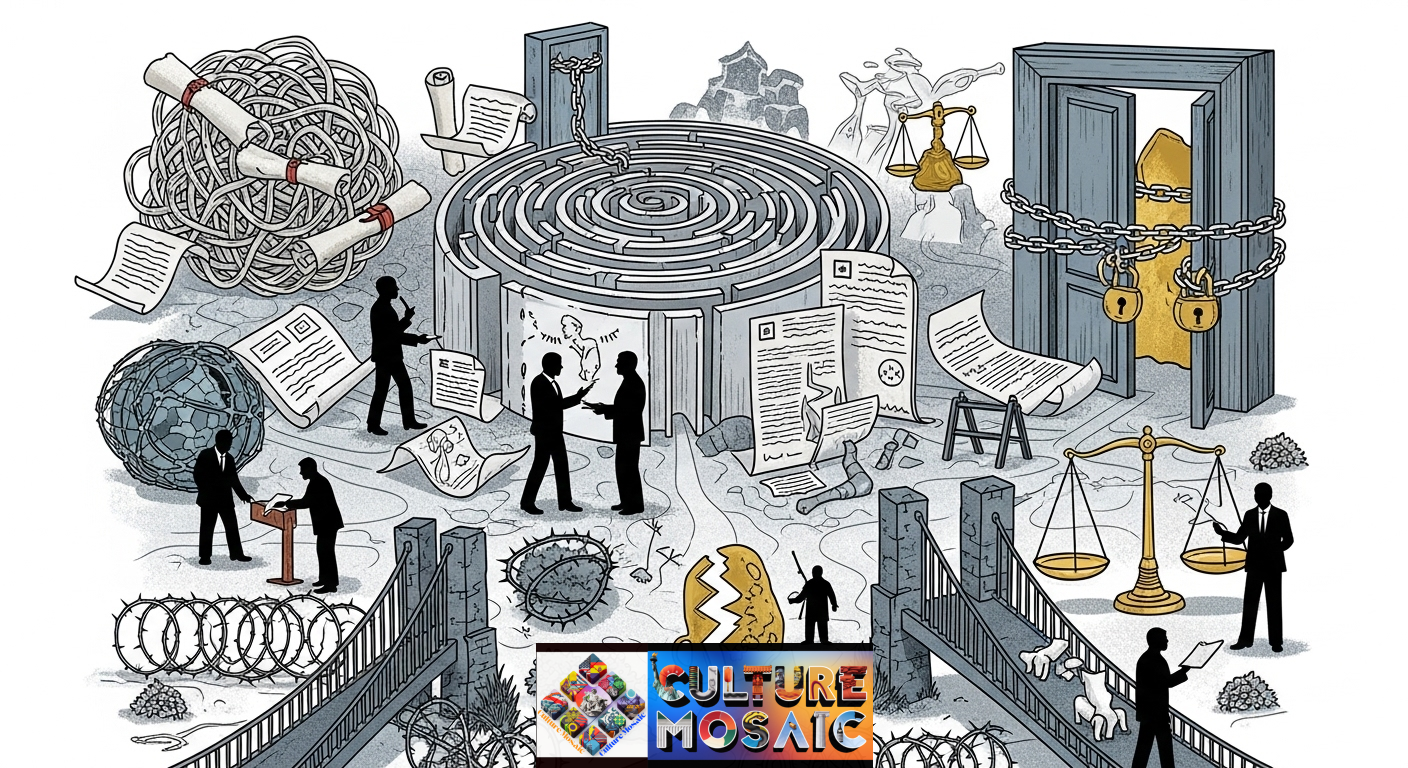

The Legal and Political Obstacles to Repatriation

Making the moral case for repatriation is easier than navigating the legal and political reality. Museums operate under complex regulations that govern their collections. Many institutions are legally prohibited from deaccessioning objects—permanently removing them from their collections—without meeting specific criteria.

In the United States, federal museums face particularly stringent rules. Even when curators and administrators want to return objects, they may need Congressional approval or must demonstrate that items meet narrow legal definitions. Private museums have more flexibility but may face pressure from donors, board members, or founding charters that emphasize collecting over returning.

International repatriation is even more complicated. There’s no global law requiring countries to return cultural property, though UNESCO conventions provide frameworks for cooperation. Each case often requires bilateral negotiations between governments, which can take years or decades.

Provenance research—tracing the ownership history of an object—is another challenge. Records are often incomplete, especially for objects acquired in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Museums may genuinely not know how certain items entered their collections, making it difficult to determine rightful owners.

Some source countries also lack the infrastructure to properly care for returned objects. While this shouldn’t be used as an excuse to avoid repatriation, it’s a practical concern that requires good-faith cooperation. Several repatriation agreements have included provisions for museum professionals from the returning institution to help train staff and develop conservation facilities in the receiving country.

Money is always an issue. Repatriation costs money—for research, for shipping, for legal processes. Museums often claim they lack the resources, especially smaller institutions. Yet many of these same museums found money to acquire the objects in the first place.

Success Stories: When Repatriation Works

Despite the obstacles, repatriation is happening, and it’s worth celebrating the cases that get it right.

In 2022, the Horniman Museum in London announced it would return 72 artifacts to Nigeria, including several Benin Bronzes. Unlike other institutions that hemmed and hawed about legal complications, the Horniman simply acknowledged that the objects were looted and should go back. The transfer happened within months.

The University of Aberdeen in Scotland returned a Benin Bronze to Nigeria even earlier, in 2021, becoming one of the first institutions to do so. They didn’t wait for a formal request—they proactively reached out to Nigerian authorities.

In the United States, several museums have made significant progress on NAGPRA repatriations. The Denver Museum of Nature & Science returned the remains of more than 200 Native American individuals to various tribes. The Field Museum in Chicago has been working closely with Native American communities for years on repatriation and has developed what many consider a model consultation process.

France passed legislation allowing the return of 26 looted objects to Benin and a sacred sword to Senegal, setting a precedent that other European nations are now watching closely. Germany has committed to the largest-scale repatriation effort yet, planning to return hundreds of Benin Bronzes.

These successes share common elements. Leadership matters—museum directors and board members who genuinely believe in repatriation can overcome institutional inertia. Building relationships with source communities, rather than treating repatriation as a transaction, makes the process smoother. And public transparency, rather than quiet negotiations, builds trust and momentum.

What Comes Next for the Repatriation Movement

The repatriation movement isn’t slowing down. If anything, it’s accelerating as younger generations enter museum leadership positions and the general public becomes more aware of collection histories.

We’re likely to see more legislation similar to NAGPRA expanded to cover other categories of objects or extended to private collections. Several US lawmakers have proposed bills that would strengthen repatriation requirements and provide more funding for the process.

The definition of what should be repatriated may also expand. Current discussions focus primarily on items taken through colonization, looting, or grave robbing. But what about objects acquired through unequal power dynamics, even if technically “legal” at the time? This question opens up vast areas of museum collections to potential claims.

Museums themselves are changing. New institutions being built today often incorporate repatriation principles from the start, with policies that prioritize collaboration with source communities and acknowledge that some objects don’t belong in museums at all. The concept of museums as neutral, authoritative institutions is fading, replaced by a vision of museums as community resources that must earn their social license to operate.

The repatriation movement also intersects with broader conversations about racial justice, Indigenous rights, and decolonization. It’s not separate from these struggles—it’s an essential part of them. For many activists, repatriation is one concrete way to address historical wrongs and shift power dynamics that persist today.

Perhaps most importantly, repatriation is forcing uncomfortable but necessary conversations about what museums are for and who they serve. The old model—where museums collected whatever they wanted and the public was grateful for access—is dying. The new model, still taking shape, centers the voices of those whose heritage fills the display cases.

How You Can Support Repatriation Efforts

If you’re convinced that repatriation matters, you don’t have to be a museum professional to make a difference.

Start by educating yourself about the collections in your local museums. Most institutions now have online databases. Look at objects from other cultures and ask yourself: how did this get here? Many museums are beginning to include acquisition information, though you might need to dig.

When you visit museums, ask questions. Docents and staff should be able to explain the provenance of objects. If they can’t, that’s worth noting. Comment cards and visitor feedback can influence museum policies, especially at smaller institutions where leadership pays attention to community input.

Support Indigenous-led museums and cultural centers. When Native American tribes open their own museums to share their cultures on their own terms, they’re building an alternative to the extraction model of traditional museums. Your admission fee or donation directly supports these communities.

Follow and amplify the voices of people from affected communities who are doing repatriation work. Social media has democratized these conversations—you can learn directly from Native American activists, African scholars, and museum professionals who are pushing for change.

If you’re a museum member or donor, use that position to advocate for repatriation. Board members and directors pay attention to their supporters. Letting them know that you value ethical collections management over encyclopedic holdings can shift institutional priorities.

Finally, recognize that repatriation isn’t about emptying museums. It’s about justice, respect, and giving communities the agency to decide what happens to their cultural heritage. Museums can still be amazing places full of wonder and learning. They just need to be more honest about their histories and more generous about their futures.

Frequently Asked Questions About Repatriation

1. Won’t repatriation empty museums and leave them with nothing to display?

No. Most repatriation claims affect a small percentage of museum collections. Museums have plenty of objects that were ethically acquired, donated by their creators, or purchased through legitimate means. What repatriation does is remove objects that never should have been in museums in the first place—human remains, sacred objects, and looted artifacts. Museums can fill those spaces with objects they have every right to display, or they can create new exhibits about repatriation itself, which many visitors find fascinating.

2. If an object has been in a museum for 100+ years, isn’t it too late to return it?

Time doesn’t make theft legitimate. Many communities have been requesting the return of their cultural property for decades but lacked the political or legal power to force the issue. The fact that museums kept objects for a long time doesn’t give them ownership rights, especially when those objects were acquired through colonization or looting. Some argue that long-term possession creates a form of custodianship, but that’s increasingly seen as a way to avoid accountability rather than a genuine legal or moral principle.

3. What happens to repatriated objects after they’re returned?

This varies by community and object. Some sacred objects are returned to active ceremonial use. Human remains are typically reburied according to traditional practices. Museum-quality artifacts might go to national or community museums in the country of origin. Some communities choose to keep objects in secure storage, accessible only to authorized individuals. The key point is that the source community decides, not outside institutions. Their choices deserve respect even if they differ from Western museum practices.

4. Are museums compensated when they return objects?

Generally, no. Repatriation is based on the principle that museums shouldn’t have had the objects in the first place, so compensation would essentially be paying them for stolen property. In some negotiated agreements, the receiving country might offer to loan other objects or provide cultural exchanges, but these are gestures of goodwill rather than payment. The financial value of repatriated objects is irrelevant to the moral and legal obligation to return them.

5. How can I tell if an object in a museum should be repatriated?

Look for several red flags: objects labeled as coming from “private collections” with no earlier provenance; items acquired during colonial periods from Africa, Asia, or the Americas; human remains displayed without clear consent from descendants; sacred or ceremonial objects from Indigenous communities; and objects with suspiciously vague acquisition information. Museums are getting better about provenance transparency, but if information seems deliberately vague or is missing entirely, there’s often a reason. Trust your instincts—if an object’s presence in a museum feels wrong once you know its history, you’re probably right.