Between 1916 and 1970, over six million African Americans migrated from the rural South in search of better opportunities in northern and western cities. They carried more than dreams in their suitcases – they brought cuisine, cooking techniques, and food traditions that would forever shape American dishes. This Pak journey that we now recognize as a migration plate: a dynamic collection of cuisine that developed from the southern roots into urban classics.

Understanding the Migration Plate in American Food History

Migration plate represents more than a simple collection of cuisine. It is a living document of flexibility, adaptation, and cultural protection. When the African American communities in Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, and New York City reached cities, they faced a completely new food landscape. Corner stores replaced outdoor cooking pits instead of the country’s gardens, apartment kitchens, and developed migrationplates to meet these challenges, respecting the ancestral tastes.

This change did not happen in isolation. Migration plate became a bridge between generations, a way to maintain a new urban identity and maintain a relationship with the Southern Homelands. Every dish tells a story of simplicity – how the taste of Sunday dinner is different from the taste of the dinner when the material, equipment, and even water are different.

The Migration Plate’s Journey from Southern Roots to Urban Tables

Southern cooking before the Great Migration centered on what was available: vegetables from kitchen gardens, chickens raised in backyards, and whole hogs roasted for community gatherings. Cooking methods relied on open fires, cast iron, and time—lots of time. The migrationplate had to adapt when families moved into cramped tenement apartments with limited kitchen space and different fuel sources.

Urban grocery stores didn’t stock the same ingredients that Southern families grew themselves. Collard greens might be available, but not always fresh. Pork cuts became individualized—chops and ribs instead of whole animals. The migration plate transformed out of necessity, but cooks refused to compromise on flavor. They found new ways to achieve familiar tastes, creating hybrid dishes that honored the past while embracing urban realities.

How the Migration Plate Transformed BBQ Traditions

Traditional Southern BBQ involved whole-hog roasting over open pits—a communal event that took days and fed entire communities. The migration plate couldn’t accommodate this practice in urban settings, so BBQ evolved. Individual cuts became the standard: ribs, brisket, chicken pieces. These smaller portions suited apartment living and the faster pace of city life.

Chicago’s South Side became legendary for its BBQ joints, where the migration plate adapted Southern smoking techniques to urban equipment. Pitmasters created aquarium smokers—enclosed units that could operate in tighter spaces without overwhelming neighborhoods with smoke. The flavors remained authentic, but the methods transformed. Detroit, Kansas City, and Los Angeles each developed their own regional BBQ style, all rooted in Southern traditions but distinctly shaped by their new urban environments.

The Evolution of MigrationPlate Regional Specialties

As the migration plate spread across America, regional variations emerged based on local ingredients and influences. Chicago’s mild sauce—a tangy, sweet condiment found nowhere else—became a signature of the city’s migrationplate identity. It paired perfectly with fried chicken and represented the kind of culinary innovation that happened when Southern cooks encountered new urban food cultures.

Detroit’s migration plate incorporated automotive industry shift work schedules, leading to 24-hour soul food restaurants that served breakfast at midnight. Los Angeles blended Southern cooking with Mexican and Asian influences, creating unique fusion dishes. Each city’s migration plate reflected not just where people came from, but where they were building new lives.

Soul Food on the Migration Plate: Preservation and Innovation

Soul food—the term itself didn’t become popular until the 1960s—represents the heart of the migration plate. Dishes like fried chicken, collard greens, black-eyed peas, cornbread, and sweet potato pie traveled north as touchstones of identity and comfort. But the migrationplate couldn’t simply replicate Southern soul food; it had to evolve.

Urban cooks found creative substitutions when traditional ingredients weren’t available. The migration plate featured new techniques for achieving that slow-cooked flavor in less time. Pressure cookers became essential tools, allowing working families to prepare traditional meals on tight schedules. Weekend cooking marathons produced meals for the entire week, with soul food dishes carefully portioned and stored—a practice that continues in many Black American households today.

Migration Plate Economics: From Farm to City Market

The economic shift from rural to urban life dramatically impacted the migration plate. In the South, many families grew their own food or bartered with neighbors. City living meant everything had to be purchased, and at higher prices. The migrationplate became a study in economic efficiency without sacrificing flavor or cultural significance.

Cheaper cuts of meat—oxtails, neck bones, pig feet—that had always been part of Southern cooking became even more important in urban kitchens. The migration plate showed how culinary skill could transform humble ingredients into deeply satisfying meals. This economic creativity wasn’t new, but it became more visible and valued as soul food restaurants emerged in Northern cities, turning the migration plate into a legitimate business opportunity.

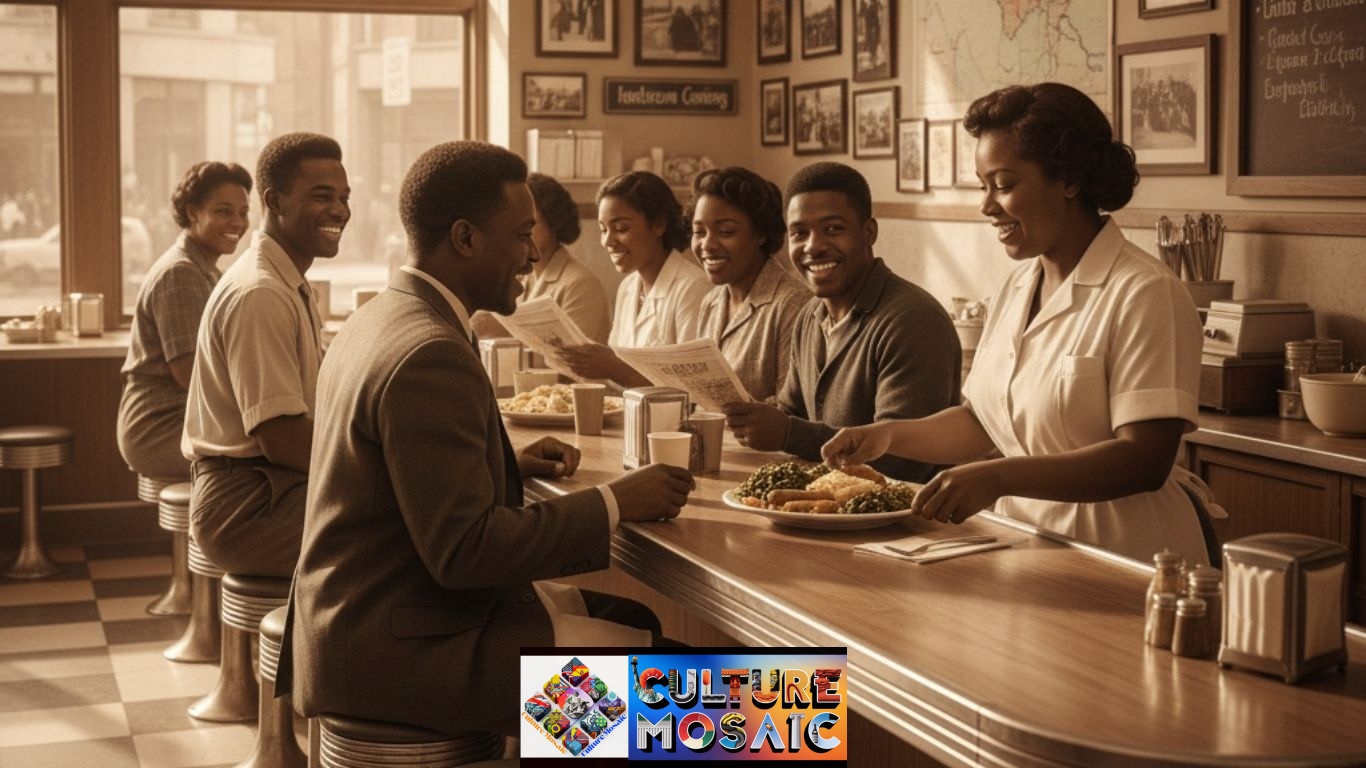

The Role of Diners and Lunch Counters in Migration Plate Culture

Diners and lunch counters became sacred spaces for the migration plate. These establishments served as more than restaurants—they were community centers, news exchanges, and safe havens where Black Americans could relax in an often-hostile urban environment. The migrationplate on these counters represented home, even for those who’d never been to the South.

Proprietors often came from specific Southern regions and specialized in their hometown cooking. A Mississippi native might run a diner featuring Delta-style tamales alongside classic soul food, while someone from the Carolinas might focus on mustard-based BBQ sauces. These establishments preserved regional variations within the broader migration plate tradition, creating a culinary map of the South within Northern cities.

Migration Plate Techniques: Adapting Cooking Methods to Urban Spaces

Outdoor pit smoking wasn’t possible in most urban apartments, so the migration plate developed new techniques. Stovetop smoking, oven roasting with liquid smoke, and the strategic use of spice rubs allowed cooks to approximate traditional flavors in limited spaces. Cast iron skillets became even more essential, serving as versatile tools for frying, baking, and braising.

The migrationplate also saw the rise of one-pot meals—dishes like gumbo, jambalaya, and red beans and rice that could cook on a single burner, conserving both space and fuel. These techniques represented culinary intelligence, the kind of problem-solving that doesn’t make headlines but fundamentally shapes how people eat and live.

How the Migration Plate Influenced Mainstream American Cuisine

The migration plate didn’t stay confined to Black neighborhoods. As the 20th century progressed, soul food and BBQ entered mainstream American consciousness. Restaurants, cookbooks, and eventually food media began celebrating what had long been considered humble fare. The migrationplate’s influence can be seen in everything from fast-food fried chicken chains to upscale restaurants featuring “elevated” soul food.

This mainstreaming brought both recognition and tension. While increased visibility meant more appreciation for the migration plate’s contributions to American cuisine, it also raised questions about cultural appropriation, credit, and compensation. The migrationplate’s journey into mainstream culture reflects larger conversations about race, credit, and whose stories get told in American food history.

The Migration Plate in Contemporary Black American Identity

Today’s migration plate continues evolving while honoring its roots. Third and fourth-generation descendants of Great Migration families maintain cooking traditions passed down from grandparents who made that journey. Food blogs, social media, and cookbooks ensure that migration plate recipes and stories reach new audiences.

Contemporary chefs are reexamining the migrationplate with fresh perspectives, exploring its history while innovating with modern techniques and presentations. This isn’t abandoning tradition—it’s continuing the migration plate’s legacy of adaptation and evolution. Just as urban cooks in the 1920s modified whole-hog BBQ for apartment living, today’s cooks are finding new ways to honor and extend migrationplate traditions.

Migration Plate Grocery Shopping: Then and Now

The grocery store experience shaped the migration plate as much as any cooking technique. Early migrants encountered Northern stores stocked differently than Southern country stores or markets. Certain ingredients simply weren’t available; others were prohibitively expensive. The migrationplate adapted through substitution and creativity.

Today, specialized grocery stores in historically Black neighborhoods stock ingredients crucial to the migration plate: smoked turkey parts for flavoring greens, specific hot sauce brands, fresh collards year-round, and the right cuts of pork. These stores serve as cultural institutions, preserving the migrationplate’s ingredient traditions while also embracing contemporary dietary preferences like vegetarian soul food options.

The Migration Plate’s Chicago-Style Mild Sauce Innovation

Chicago’s mild sauce deserves special attention in migration plate history. This sweet, tangy, slightly spicy condiment emerged from Chicago’s South and West sides, appearing on migrationplate menus in the 1950s and ’60s. Unlike anything found in the South, mild sauce represents pure urban innovation—what happens when the migrationplate settles into a specific place long enough to create something entirely new.

Mild sauce typically accompanies fried chicken, rib tips, and fries, creating a flavor profile uniquely Chicagoan while still fitting within soul food traditions. Its creation demonstrates how the migrationplate wasn’t just about preservation—it was also about innovation, about creating new traditions while honoring old ones. Every city where the Great Migration brought Southern families developed similar innovations, making the migrationplate a living, evolving cuisine rather than a museum piece.

Preserving Migration Plate Stories Through Food

The migration plate carries stories that might otherwise be lost. When families gather around Sunday dinner, they’re not just eating—they’re maintaining connections to ancestors, to Southern homelands, and to the courage it took to leave everything familiar for uncertain opportunities. These meals encode history in ways that textbooks can’t capture.

Documentation efforts—from cookbooks to oral history projects to food museums—increasingly recognize the migration plate’s cultural significance. Preserving recipes is important, but the stories behind them matter just as much. Why did this grandmother always add a pinch of sugar to her collard greens? What did that grandfather’s BBQ sauce recipe mean to him as he built a new life in Detroit? The migrationplate answers these questions deliciously.

The Future of the Migration Plate in American Food Culture

The migration plate‘s journey continues. Contemporary food movements—farm-to-table, nose-to-tail cooking, fermentation—are recognizing practices that the migrationplate has employed for generations. Younger generations are reclaiming and redefining soul food, exploring its nutritional aspects, environmental impact, and ongoing relevance.

Climate change, urban farming initiatives, and food justice movements are all influencing how the migration plate evolves next. Community gardens in former migration cities allow families to grow traditional Southern vegetables again, closing a circle opened a century ago. The migrationplate demonstrates that cuisines aren’t static—they’re conversations across generations, always responding to new circumstances while maintaining core values of flavor, community, and cultural identity.

FAQs

What exactly is a migration plate in culinary history?

The migration plate refers to the collection of African American foods and cooking traditions that traveled from the rural South to Northern and Western urban centers during the Great Migration (1916-1970). It encompasses BBQ, soul food, and regional specialties that evolved as Southern cooks adapted their traditional methods to urban kitchens, different ingredients, and new equipment while preserving essential flavors and cultural connections.

How did BBQ change as part of the migration plate movement?

BBQ transformed dramatically in the migration plate evolution. Traditional whole-hog roasting over open pits became impractical in urban settings, so pitmasters adapted to individual cuts like ribs, brisket, and chicken pieces. They developed enclosed smokers suitable for city environments, created new regional sauces, and established BBQ restaurants that served as community gathering spaces while maintaining authentic Southern smoking traditions in modified forms.

Why are diners and lunch counters important to migration plate history?

Diners and lunch counters were sacred spaces for the migrationplate because they served as community centers, safe havens, and culinary preservation sites for Black Americans in often-hostile urban environments. These establishments didn’t just serve food—they maintained regional Southern cooking styles, provided gathering places for news and socializing, and turned the plate into both cultural touchstone and business opportunity during the Great Migration era.

What is Chicago-style mild sauce, and why is it significant?

Chicago-style mild sauce is a sweet, tangy, slightly spicy condiment created in Chicago’s Black neighborhoods during the 1950s-60s migrationplate era. It’s significant because it represents pure urban innovation—a completely new creation that emerged when Southern food traditions settled long enough in one place to develop original dishes. Typically served with fried chicken and rib tips, mild sauce exemplifies how the migration plate wasn’t just about preservation but also about creating new culinary traditions.

How does the migrationplate continue influencing modern American food?

The migrationplate continues shaping American cuisine through mainstream appreciation of BBQ and soul food, contemporary chefs reinterpreting traditional dishes, food justice movements recognizing historical cooking practices, and younger generations reclaiming these traditions while innovating. Its influence appears in everything from fast-food chains to upscale restaurants, while ongoing documentation efforts preserve migration plate stories and recipes, ensuring this culinary legacy remains vibrant and evolving rather than static or forgotten.