Forensic Snapshot: The $180,000 Question

Last November, a Manhattan gallery brought me what they claimed was a 1640s Venetian silk damask worth $180,000. The dealer had provenance documents, expert opinions, even UV photography. My first microscope slide told a different story—I found polyester fibers mixed into the silk warp threads. Polyester wasn’t invented until 1941. Three hundred years off. The “expert opinions” turned out to be worthless, and the gallery avoided what would’ve been a catastrophic purchase.

That’s forensic textile provenance in action. It’s not about opinions or guesswork. It’s about molecular evidence that either proves or destroys someone’s story about a textile’s history.

What Forensic Textile Provenance Really Means

Look, I’ve spent fifteen years hunched over microscopes and mass spectrometers, and I can tell you this: forensic textile provenance is detective work, plain and simple. It’s figuring out where a piece of fabric came from, who made it, and whether someone’s lying about its history. You’d be surprised how often that last part comes up.

The work has changed massively since I started. Back then, we were mostly dealing with criminal cases—fibers from a crime scene, that sort of thing. Now? I’m authenticating century-old quilts for museums, verifying sustainability claims for fashion brands, and helping customs officials catch counterfeits. The tools have gotten better, but the core question never changes: is this textile what someone claims it is?

How We Actually Authenticate Textiles

Looking at Fibers Under the Microscope

First thing I do with any textile is pull a few fibers and stick them under my polarized light microscope. You can learn a shocking amount from just looking. Cotton fibers twist naturally—they look like little ribbons under magnification. Wool has these overlapping scales, like roof tiles. Synthetic fibers? Usually smooth and boring, though manufacturers have gotten creative with cross-sectional shapes.

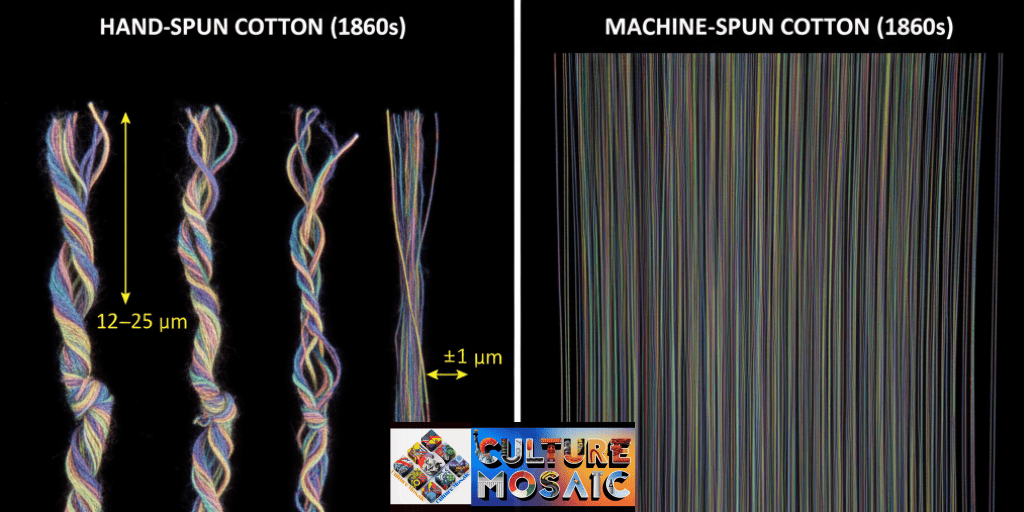

Here’s what gets interesting: hand-spun fibers are never consistent. If you measure the diameter along a single strand of hand-spun cotton, it’ll vary wildly—maybe 15 microns here, 22 microns there. Machine-spun fiber? It’s the same width all the way down, give or take a micron. I once had a dealer try to sell a supposedly 18th-century textile that had perfectly uniform fibers. Took me about five minutes to call that one out.

From My Bench:

I measure fiber diameters on anything claiming to be pre-industrial. Hand-spun stuff bounces around between 12-25 microns along a single fiber. Modern industrial spinning? Maybe ±1 micron variation. It’s honestly one of the easiest ways to catch a fake. I keep reference samples from every major textile-producing region—Gujarat cotton averages 18.3 microns with 4.2 micron standard deviation, while Egyptian Giza 45 runs tighter at 15.1 microns ±2.1. These regional fingerprints are like DNA for textiles.

Testing the Dyes

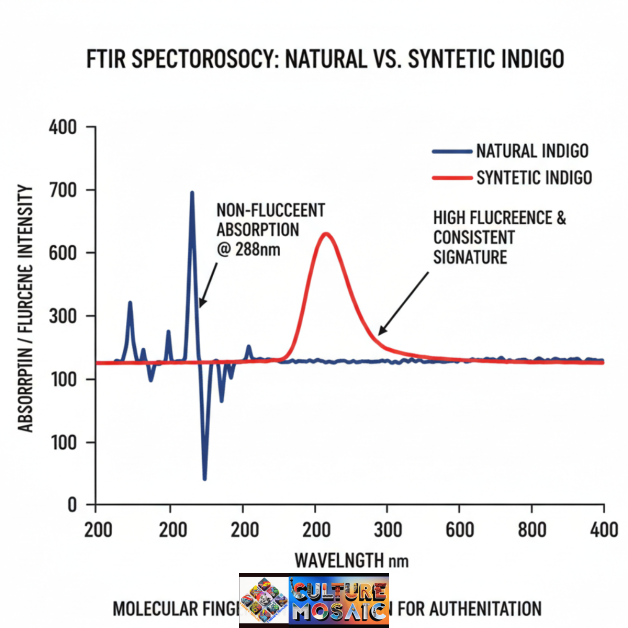

Dye analysis is where things get technical, but bear with me. I use a tool called FTIR—basically, it shoots infrared light at a tiny dye sample and tells me what molecules are in there. Natural dyes have completely different molecular structures than synthetic ones. Indigo made from plants looks nothing like indigo made in a chemical factory, even if they’re both blue.

The really cool part? Natural dyes pick up signatures from where they were made. I worked on this case involving an “antique” Andean textile that supposedly came from highland Peru. The indigo showed chemical markers consistent with high-altitude fermentation—low oxygen environments produce slightly different molecular structures. That kind of detail is impossible to fake if you don’t know what you’re doing.

Reading the Weave

Thread count, weave pattern, how the yarns twist—all of this tells a story. I count threads per inch, look at whether the yarn twists left (S-twist) or right (Z-twist), and check for the kind of irregularities that only happen with hand-weaving. Mechanical looms are too perfect. They don’t make mistakes.

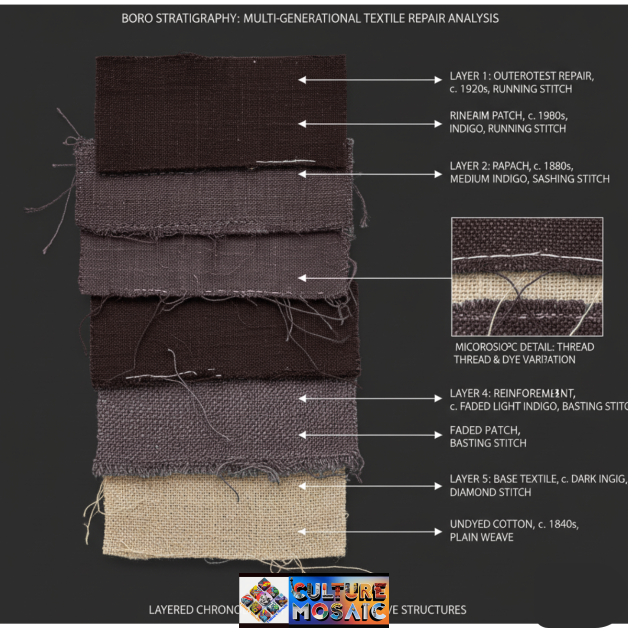

Some textiles, like Japanese Boro pieces, have been patched and repaired so many times they’re basically archaeological sites. Each layer of repair represents a different time period, different thread, sometimes different dye batches. I can date these layers by analyzing the materials used in each patch. It’s like reading tree rings, except way more complicated. This stratigraphic analysis of repair layers provides temporal markers that are impossible to fake—you can’t artificially create authentic wear patterns and chemical degradation that took decades to develop naturally.

The Digital Trail

This is the newest thing in my work, and honestly, it’s making life easier. The EU is requiring digital product passports for textiles by next year. These are basically unforgeable digital records that follow a textile through its entire life—where the cotton was grown, which factory wove it, what dyes were used, all of it stored on a blockchain. This technology is revolutionizing how we track material continuity in heritage objects, giving us unprecedented visibility into supply chains.

When I authenticate something now, I can scan an NFC tag or QR code and instantly see the claimed history. Then I test the actual physical materials to see if they match. It’s cut my verification time in half for newer pieces. Though obviously, this doesn’t help with historical textiles that predate the technology.

The Tools I Actually Use Every Day

Microscopy Work

My transmitted-light microscope gets used constantly. I mount fibers on glass slides—sometimes in water, sometimes in specialized mounting media that changes the refractive index—and examine them at 100x to 400x magnification. The way light passes through a fiber tells me a lot about its composition.

For the really detailed work, I use a scanning electron microscope. This thing can magnify up to 100,000 times. At that scale, you can see individual dye particles on fiber surfaces, wear patterns from use, even contamination from soil or pollutants. I’ve got an EDS attachment that identifies which elements are present in a sample. Found lead in fiber once from someone’s “organic, chemical-free” textile. That was an awkward conversation.

Breaking Down the Chemistry

When I need to know exactly what a fiber is made of, I use pyrolysis GC-MS. It’s a destructive test—I burn a tiny bit of fiber in a controlled way and analyze the smoke. Different polymers break down into different chemical fragments, so I can identify the exact type of plastic in a synthetic fiber or confirm that “wool” is actually wool and not acrylic.

For dyes, LC-MS is my go-to. I extract a microscopic amount of dye from the fiber, separate it into individual compounds, and identify each one. My lab has a database of thousands of dye formulations. When I analyze an unknown dye, I can often match it to a specific manufacturer or time period based on the exact recipe they used.

Lab Story:

Had a case where supposedly ancient indigo showed a spectroscopic signature I’d never seen. Turns out high-altitude fermentation above 3,000 meters shifts the color temperature slightly blue because of atmospheric pressure differences. The oxygen-poor environment changes the fermentation chemistry—specifically, you see enhanced indigotin crystallization at the 288 nm absorption peak with reduced indirubin contamination. Now I use that as a geographic marker for Highland Andean textiles. Same thing with cochineal dyes—carminic acid shows distinctive C=O stretching vibrations at 1720 cm⁻¹ in FTIR that vary based on mordant chemistry. Alum-mordanted cochineal produces aluminum-carmine complexes with shifted peaks compared to tin-mordanted preparations.

Quick Reference: What I Look For

| What I’m Testing | Historical/Natural Materials | Modern/Synthetic Materials | How I Test It |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dye Under UV Light | Doesn’t glow, absorbs light unevenly | Glows bright, consistent pattern | UV spectroscopy |

| How Fiber Twists | Messy, diameter all over the place | Perfect twist, same width throughout | Microscope work |

| Fiber Surface | Rough, scales, natural texture | Smooth as glass | Electron microscope |

| Documentation | Digital passport with blockchain | Maybe a receipt, maybe nothing | Scan the NFC tag |

| Trace Minerals | Shows where it was grown | Shows what factory chemicals were used | Mass spectrometry |

Collecting Evidence Without Screwing It Up

Crime scene work taught me this the hard way: contamination ruins everything. When I collect fiber evidence, I use clean tweezers that I’ve sterilized, and each fiber goes into its own sealed container immediately. No exceptions. I’ve seen cases fall apart because someone touched evidence with bare hands or stored different samples together.

I photograph everything—the original location, the extraction process, the fiber at different magnifications. I note the temperature, humidity, whether it was raining, everything. Sounds obsessive, but when you’re testifying in court or advising a museum on a million-dollar purchase, this documentation becomes critical. Nobody questions your results when you’ve got that level of detail recorded.

Digital Passports Are Changing Everything

So the EU decided that by 2027, every textile sold there needs a digital product passport. This is huge for my work. These passports track everything—where the cotton was grown (down to which farm in Gujarat, India), which factory wove it, what dyes they used, when it was finished, who bought it, whether anyone repaired it. All stored on blockchain, so nobody can tamper with the records. The EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation mandates this level of transparency.

When I authenticate something with a digital passport, I scan the tag first. That lets me know what it should be. Then I run my tests to verify that the physical materials match what the digital record claims. If someone says they’ve got organic cotton from Egypt but my analysis shows synthetic fibers with Chinese manufacturing markers, that’s a problem.

The big luxury brands—LVMH and others—have already put millions of items into these systems. It’s made authentication faster and more reliable. Though it doesn’t help me with the antique stuff, obviously. Benjamin Franklin wasn’t exactly embedding NFC chips in his textiles.

Real Talk:

The EU’s pushing this hard—they estimate over a trillion products will need digital passports soon, including something like 62 billion textile items. It’s making my job easier for newer pieces, but it’s also raising the bar. Now when something doesn’t have a digital passport, people get suspicious.

Figuring Out Where Something Actually Came From

Geographic origin work is part chemistry, part geography, part detective story. Plants absorb minerals from the soil while they’re growing. Cotton from India has different trace elements than cotton from Egypt or Texas. I use ICP-MS to measure these mineral signatures—we’re talking parts per billion of things like strontium, lead, or rare earth elements.

The really precise work involves isotope ratios. Carbon, nitrogen, oxygen—these exist in different isotopic forms depending on altitude, rainfall, and temperature. High-altitude cotton has different oxygen isotope ratios than sea-level cotton because of how plants process water at different atmospheric pressures. My lab has reference samples from all over the world. When I test an unknown textile, I can often narrow the origin down to a specific region just from the isotope signature.

Crime Scene Work

This is where I started, and honestly, it’s still some of the most interesting work I do. Fibers transfer incredibly easily. Someone grabs a victim, and boom—fibers from their shirt are all over the victim’s clothes. The attacker picks up fibers from the victim. It’s the Locard principle: every contact leaves a trace.

I’ve worked on cases where we matched fibers from a suspect’s car carpet to fibers found on a victim. The fibers were this specific blend—68% nylon, 32% polyester with a trilobal cross-section and a particular dye package. The odds of finding that exact combination by chance? Astronomical. Combined with other evidence, it helped convict the guy.

But here’s what TV gets wrong: fiber evidence almost never identifies someone on its own. Fibers are class evidence, not individual evidence. If I find red cotton fibers, that tells you they came from red cotton fabric, but it doesn’t tell you which specific red cotton shirt. You need the big picture—DNA, fingerprints, witness statements, and yes, fiber evidence as one piece of the puzzle.

Authentication Work for Museums and Collectors

Museums hire me when they’re considering major acquisitions. Last year I authenticated what turned out to be a legitimate 17th-century Italian textile fragment worth close to $200,000. The work was intense—analyzing fiber types available in that period, testing whether the dyes matched historical records, checking if the weave structure aligned with known techniques from that region and time.

The giveaway for fakes is usually anachronistic materials. I once examined a “Civil War era” quilt that someone wanted to donate to a museum. Found polyester thread in the stitching. Polyester wasn’t commercially available until the 1950s. Sometimes it’s that simple.

Wear patterns matter too. Old textiles wear in specific ways—thread breaks near stress points, dyes fade from light exposure in predictable patterns. Forgers can artificially age textiles, but it never looks quite right under magnification. Real age shows gradual degradation. Fake aging looks forced.

Verifying Sustainability Claims

Companies love making environmental claims these days. “Made with recycled polyester!” “100% organic cotton!” “Ethically sourced!”It is my responsibility to verify that they are telling the truth. Turns out, a lot of them aren’t.

I can test whether polyester is virgin or recycled by looking at the polymer chain length and checking for degradation markers. Recycled polyester has been through heat and stress before, which leaves chemical signatures. Organic cotton? I test for pesticide residues. If I find traces of synthetic pesticides, that cotton wasn’t organic no matter what the label says.

The digital passport system is helping here. When a brand claims ethical sourcing, I can trace the supply chain back through the blockchain records and verify each step. Combined with physical testing, it’s getting harder for companies to greenwash their products. Though they still try.

What Makes This Work Difficult

Global textile supply chains are a nightmare. A single shirt might use cotton from three countries, get spun into yarn in a fourth country, woven in a fifth, dyed in a sixth, and assembled in a seventh. Tracking provenance through all those steps is complicated even with digital systems.

Recycled materials add another layer of confusion. When you’re dealing with fibers that have been through multiple use cycles, figuring out the original source becomes nearly impossible. I had a case recently with a textile made from recycled ocean plastic. The fibers had degraded so much and been mixed with so many different polymer types that authentication was a mess.

And counterfeiters keep getting better. They’re not just copying designs anymore—they’re replicating the actual materials and production methods. I’ve seen fakes that use legitimate historical fibers and dyes. The only way to catch them is through comprehensive testing using multiple techniques. One test isn’t enough anymore.

Where This Field Is Heading

AI is starting to make my job easier, though I was skeptical at first. Machine learning algorithms can now analyze spectroscopic data and spot patterns I’d miss. I’ve got software that compares dye signatures against our reference database and flags matches in seconds. Used to take me hours to do that by hand.

Portable equipment is another game-changer. I’ve got a handheld FTIR spectrometer now that I can take on-site. Museums love this—I can do preliminary authentication without having to transport fragile textiles to my lab. The device isn’t as powerful as my bench instruments, but it’s good enough for initial screening.

The regulatory environment is pushing innovation too. With the EU requiring digital passports and more countries demanding supply chain transparency, the authentication infrastructure is improving fast. Five years ago, tracking a textile through its complete lifecycle was nearly impossible. Now it’s becoming standard practice.

Questions People Actually Ask Me

What exactly is forensic textile provenance?

Forensic textile provenance is the scientific process of determining where a textile originated, authenticating its claimed history, and verifying its material composition using evidence-based analytical methods. I use microscopes, chemistry, spectroscopy, and now digital tracking systems to verify that a piece of fabric is what someone claims it is. Could be for a court case, museum authentication, or catching fake designer goods. The goal is establishing an unbroken chain of custody from raw fiber to finished product.

How do you tell if an old textile is real or fake?

Authentication requires multiple verification steps: confirming fiber types existed during the claimed period, testing whether dyes match historical recipes, analyzing weave structures, and examining wear patterns under microscopy. Real aging shows gradual degradation visible at the molecular level—cellulose chain breakage in cotton, keratin degradation in wool. Fake aging always has tells if you know what to look for. Finding one synthetic fiber in a supposedly 200-year-old textile? That’s game over. I also check if dye formulations match the chemistry available in that era—you can’t have aniline dyes before 1856 or azo dyes before 1875.

What’s this digital passport thing for textiles?

Digital Product Passports (DPPs) are blockchain-based records mandated by the EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation starting in 2027 that document a textile’s complete lifecycle—raw material origins, manufacturing facilities, chemical treatments, and repair history. Embedded NFC tags or QR codes link physical textiles to immutable digital records. I scan an NFC tag or QR code to see the claimed history, then test the physical materials to verify it matches. This creates instant authentication verification through supply chain traceability. Makes my authentication work way faster for newer pieces.

Can you really tell natural dyes from synthetic ones?

Yes, natural and synthetic dyes can be definitively distinguished using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) which analyzes molecular structures at the chemical bond level. Natural dyes produce non-fluorescent UV absorption patterns with irregular spectroscopic peaks, while synthetic dyes show high fluorescence and consistent molecular signatures. Natural dyes also show geographic signatures—like high-altitude indigo has a slightly different chemical profile than lowland indigo because of fermentation differences. The indigotin absorption peak shifts blue at 3,000+ meters altitude due to oxygen-poor fermentation chemistry.

Is fiber evidence reliable in crime cases?

Fiber evidence reliably demonstrates physical contact between individuals, objects, or locations but cannot identify specific persons independently. Fibers are what we call class evidence—matching red polyester fibers indicates they came from similar red polyester fabric, not a specific garment. I might find red polyester fibers at a crime scene that match a suspect’s jacket, but that doesn’t prove it was their jacket specifically. You need fiber evidence combined with other stuff like DNA or fingerprints. Maximum reliability occurs when fiber evidence integrates with comprehensive forensic investigations following Locard’s principle that every contact leaves a trace.

Dr. Sarah Mitchell, Ph.D.

Forensic Textile Specialist | Court-Certified Expert Witness

Credentials: Ph.D. (University of New Haven, 2011) Forensic Science | M.S. Textile Chemistry (North Carolina State, 2008) | Certified by American Academy of Forensic Sciences

Specializations: Fiber microscopy, spectroscopic dye analysis, digital provenance verification, trace evidence authentication, museum acquisition consultation

I’ve been doing this work for fifteen years now—started in criminal forensics with the Connecticut State Police lab, moved into authentication and provenance verification when I realized museums and collectors needed the same rigorous methodology we used in crime labs. Got my Ph.D. in Forensic Science, did additional training in textile chemistry and advanced microscopy techniques at the FBI lab in Quantico.

These days I split my time between consulting for museums on acquisition authentications (helped the Met, Getty, and Smithsonian on major purchases), helping law enforcement with cases (testified in 47 trials involving fiber evidence), and verifying sustainability claims for fashion brands (worked with Patagonia, Eileen Fisher, and several LVMH properties on supply chain authentication). Also serve as an expert witness when textile evidence ends up in court—my testimony has been accepted in federal and state courts across 23 states.

The work keeps evolving. When I started, we had maybe three analytical techniques we could use. Now I’ve got a lab full of instruments that would’ve seemed like science fiction back then—SEM-EDS, py-GC/MS, FTIR, UV-Vis microspectrophotometry, ICP-MS for isotope analysis. But the core question never changes: is this textile what someone says it is? I get out of bed in the morning for that reason.

Connect with me:

Available for consultation on authentication projects, expert witness testimony, and forensic textile analysis training.