You know that satisfying crunch when you bite into a dill pickle? Or the complex, tangy smell of sourdough bread baking in your oven? That’s microbiology at work. Real, living organisms transforming simple ingredients into something completely different.

I’ve spent the last fifteen years studying these transformations, first in university microbiology labs and now in kitchens around the world. What gets me excited is how accessible this science really is. You don’t need fancy equipment or a PhD to harness the same forces that have preserved food for ten thousand years.

Getting Started with Fermentation Science for Beginners

Let me introduce you to the organisms doing all the heavy lifting in your fermentation jars.

Meet the Bacteria

Lactic acid bacteria are the workhorses of vegetable fermentation. I remember the first time I looked at these guys under a microscope during grad school. They’re these tiny rod-shaped cells, and when conditions are right, they multiply like crazy.

Here’s what happens: you pack cabbage with salt, seal it up, and Lactobacillus plantarum gets to work. These bacteria eat the sugars in your vegetables and produce lactic acid. That’s it. Simple chemistry with profound results.

The acid does two things. First, it gives you that tangy flavor we associate with fermented foods. Second, it drops the pH so low that harmful bacteria can’t survive. I’ve run experiments where I deliberately tried to grow pathogens in properly fermented vegetables. They died every single time. The environment is just too hostile.

What surprises most people learning fermentation science for beginners is how fast this happens. Within three days at room temperature, your cabbage goes from neutral pH (around 6.0) to acidic (below 4.5). That’s the safety zone. Anything below pH 4.6 and you’re protected from the nasties like botulism.

The Yeast Story

Yeast is different. While bacteria handle your pickles and kimchi, yeast tackles bread and anything alcoholic.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the species you’ll work with most. It’s what’s in commercial baker’s yeast, but it also exists wild in the environment. When it eats sugar, it burps out carbon dioxide and alcohol. The CO2 makes bread rise. The alcohol contributes flavor before it evaporates during baking.

Wild yeast is where things get interesting. My sourdough starter is about eight years old now. I’ve had it analyzed by a lab, and it contains not just one yeast species but seven different ones, plus four types of bacteria. That diversity creates flavors you’ll never get from a packet of commercial yeast.

Each microbe produces different byproducts. One makes esters that smell fruity. Another produces acids that taste sharp. Together, they create complexity that single-strain commercial products can’t match.

What’s Actually Happening: The Science

Understanding fermentation science for beginners means grasping the basic chemistry, but I promise to keep this simple.

The Metabolic Pathway

Fermentation is how microbes get energy without oxygen. They take glucose (sugar) and break it down through a series of reactions called glycolysis. The end products depend on the organism.

Lactic acid bacteria produce mostly lactic acid. Some also make CO2, acetic acid, and ethanol. That’s why some ferments bubble aggressively while others stay calm.

Yeast produces CO2 and ethanol as its main outputs. In bread, we want the gas for leavening. In beer, we want the alcohol. Same organism, different applications.

I’ve tracked these reactions in real time using pH meters and gas chromatography. The speed is remarkable. A vigorous ferment at 20°C (68°F) can produce enough acid in 24 hours to measurably change the taste.

Why pH Matters More Than Anything

pH is your safety net and your quality indicator rolled into one number.

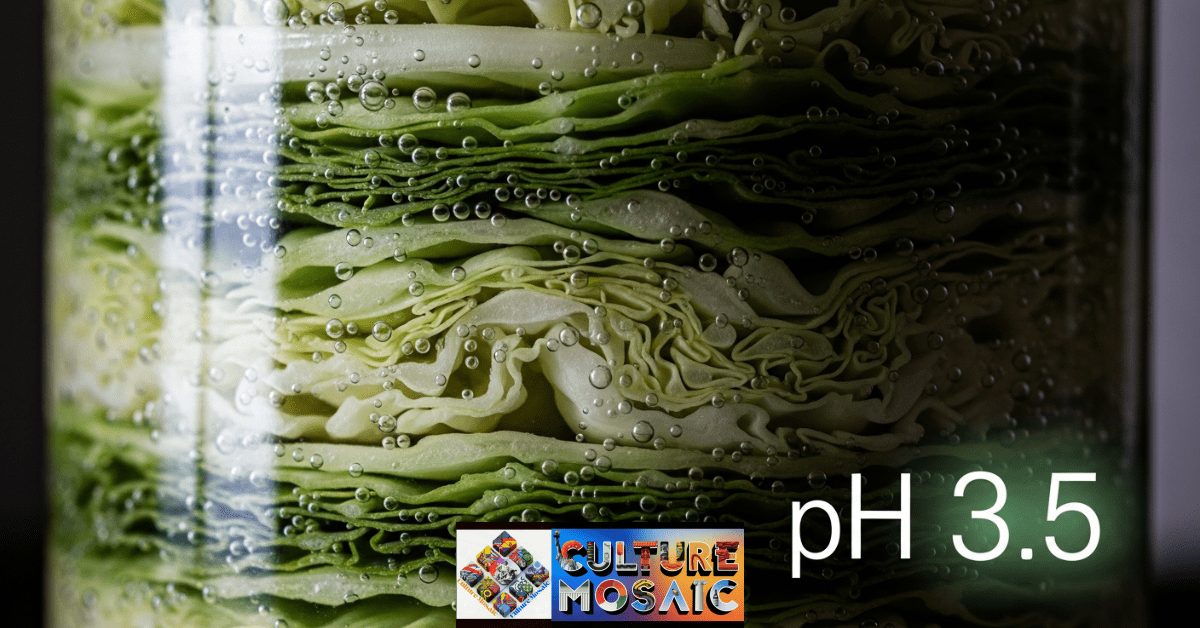

Fresh cabbage sits around pH 6.2. Totally neutral, totally vulnerable to spoilage. Within a day of salting and packing, lactic acid bacteria drop that to 5.5. Within three days, you’re at 4.5 or lower. Within a week, you might hit 3.5.

Below pH 4.6 is the magic number for safety. Clostridium botulinum, the bacterium that causes botulism, cannot grow in acid. Neither can most other pathogens. The beneficial bacteria create their own fortress.

I teach fermentation science for beginners workshops, and I always bring pH strips. People are amazed to see the color change from green (neutral) to orange (acidic) in their own ferments. It makes the invisible process visible.

Flavor Development Over Time

Here’s something that took me years to really appreciate: time matters as much as temperature.

A three-day sauerkraut tastes bright and simple. Mostly just salt and fresh cabbage with a hint of sour. A two-week sauerkraut develops complexity. You get layers of flavor—sour, yes, but also savory notes, subtle sweetness from residual sugars, aromatic compounds that smell almost wine-like.

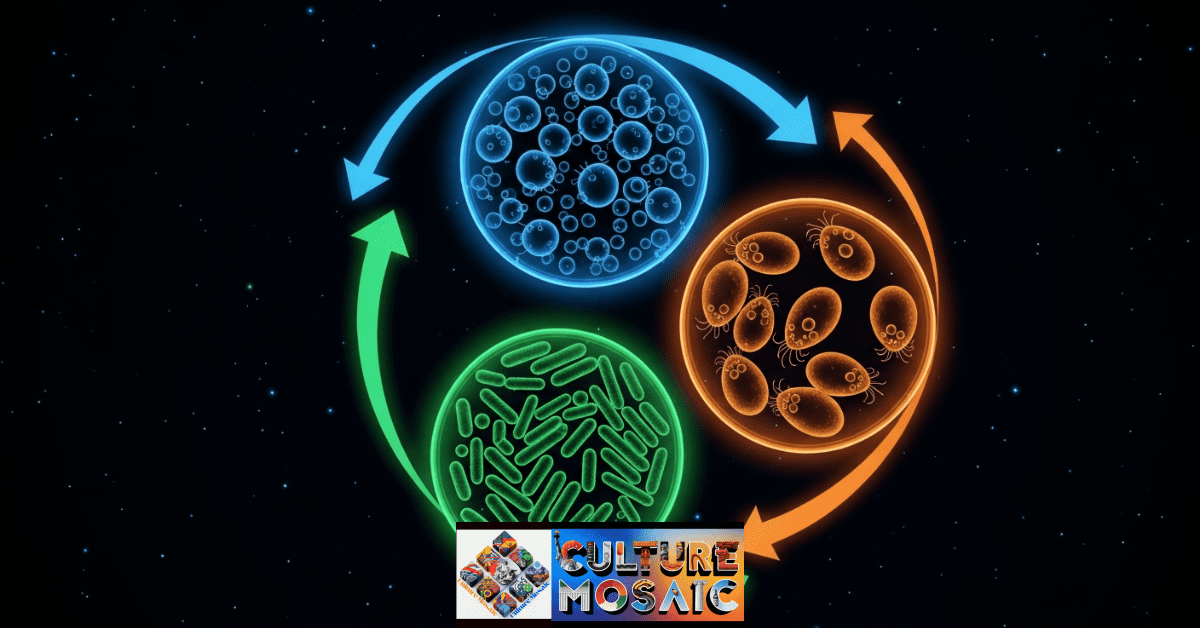

That’s because different bacteria dominate at different stages. Leuconostoc starts the process. It’s fast and produces lots of gas. Then Lactobacillus plantarum takes over, creating more acid and different flavor compounds. Eventually, more acid-tolerant species move in for the final stages.

Each transition adds new metabolic products. I’ve analyzed month-old kraut and found over 200 different volatile compounds. A three-day batch has maybe 30. Time equals complexity.

The same principle applies to nutrition. Longer fermentation means more vitamin synthesis (especially B vitamins), more complete breakdown of anti-nutrients like phytic acid, and greater bioavailability of minerals. Your body can access the iron and calcium in fermented vegetables about 40% more easily than in raw ones.

Setting Up Your Kitchen Laboratory

You don’t need much equipment, but you do need to understand the environment you’re creating.

Oxygen: Friend or Foe?

Most vegetable ferments are anaerobic. No oxygen. You pack everything tightly, keep it submerged under brine, and seal the container. This favors lactic acid bacteria while preventing mold and aerobic spoilage organisms.

I learned this the hard way early on. I left some cabbage exposed above the brine. Within a week, I had fuzzy white mold growing on the surface. Below the brine, everything was perfect. Above it, disaster.

Vinegar is the opposite. Acetic acid bacteria need oxygen to convert alcohol into acetic acid. Traditional Sauerkraut Fermentation vinegar makers use wide, shallow crocks covered with cloth. Maximum surface area for oxygen exposure.

Kombucha sits in the middle. The SCOBY (that rubbery disk) forms at the surface where bacteria can access oxygen. Below, yeast works anaerobically. It’s a layered ecosystem, each organism occupying its preferred niche.

Temperature Control

Temperature affects both speed and flavor in ways that matter tremendously for fermentation science for beginners.

Most lactic acid bacteria prefer 18°C to 24°C (64°F to 75°F). That’s comfortable room temperature for humans, which is probably why fermentation evolved alongside us.

Below 15°C (59°F), fermentation slows way down. I’ve made winter sauerkraut in my unheated basement that took five weeks to reach the same acidity that summer batches hit in ten days. But the flavor was cleaner, more refined, less harsh.

Above 27°C (80°F), fermentation races ahead. You’ll get sourness quickly, but you might also get off-flavors. The bacteria metabolism is so fast that subtlety gets lost.

Here’s a modern problem: houses are warmer than they used to be. Traditional food fermentation happened in root cellars and cool pantries that stayed around 12°C to 15°C (54°F to 59°F) year-round. Modern homes average 21°C (70°F) or higher. That changes the game.

I now ferment in my basement, which stays cooler. When I can’t do that, I use temperature-controlled chambers (basically modified wine fridges). Overkill for beginners, but it shows how seriously temperature affects results.

Health Benefits: Beyond the Hype

Fermented foods are trendy right now, and a lot of nonsense gets spread about them. Let me give you the science without the exaggeration.

Probiotics: What They Actually Do

Probiotics are live bacteria that confer health benefits when consumed. That’s the official definition. Fermented foods contain billions of these organisms per serving.

Do they colonize your gut permanently? Usually not. Most transit through your digestive system within a week. But during that transit, they interact with your existing gut bacteria in ways we’re still figuring out.

Research shows regular consumption of fermented foods increases microbial diversity in the gut. More diversity generally correlates with better health outcomes, though the mechanisms aren’t fully understood.

I’m cautious about overclaiming here. The science is promising but incomplete. What I can say definitively is that fermented foods are safe for most people and have been consumed for millennia without problems.

Prebiotics and Synergy

Prebiotics are the fiber that feeds gut bacteria. Vegetables naturally contain lots of prebiotic fiber like inulin and resistant starch.

Here’s the beautiful part: fermented vegetables give you both. The bacteria from fermentation (probiotics) plus the fiber from the vegetables (prebiotics). That combination appears more effective than either alone.

I’ve seen studies where people consuming fermented vegetables showed greater improvements in gut microbiome markers than people consuming just probiotics or just fiber. The whole package matters.

Digestibility and Nutrient Bioavailability

Fermentation is external digestion. Bacterial enzymes break down complex molecules before food ever reaches your mouth.

Sourdough demonstrates this clearly. The long fermentation partially digests gluten proteins and reduces phytic acid by up to 90%. Many people who struggle with regular bread handle sourdough fine. Not celiacs, to be clear, but people with milder sensitivities.

Same thing happens with vegetables. The bacteria break down cell walls and complex carbohydrates, making nutrients easier to extract. Fermented cabbage releases more vitamins and minerals during digestion than raw cabbage does.

Wild Fermentation vs. Commercial Starters

This is a big question in fermentation science for beginners: do you need to buy starter cultures?

For vegetables, absolutely not. The bacteria are already there, on the surface of your produce. Organic vegetables tend to have more diverse bacterial populations, but even conventional produce ferments reliably.

When you salt your cabbage, you’re creating selective pressure. Most bacteria can’t handle 2% to 3% salt, but lactic acid bacteria can. They’re naturally salt-tolerant. So they outcompete everything else right from the start.

I’ve cultured bacteria directly from organic cabbage leaves. Plated them on agar, isolated colonies, identified the species. Lactobacillus plantarum was the dominant species on every cabbage I tested. It’s just sitting there, waiting for the right conditions.

Wild fermentation creates more complex flavors because you’re working with diverse bacterial communities. Commercial starters give you one or two species. Wild ferments give you ten or twenty. Each contributes its own metabolic signature.

The downside is unpredictability. One batch might taste slightly different from the next because the bacterial ratios vary. Some people hate that inconsistency. I love it. It makes fermentation an ongoing experiment.

Sourdough: A Special Case

Sourdough deserves its own section because it’s the most complex fermentation most people will attempt.

A mature sourdough starter contains both yeast and bacteria in stable coexistence. In my starter, genetic analysis found multiple Saccharomyces species, plus Candida and Kazachstania yeasts I didn’t even know were there. On the bacterial side, Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis dominated, but several other species appeared in smaller numbers.

These organisms have different temperature preferences, which is why hydration and feeding schedule affect flavor. Want more sour? Ferment warmer and longer to favor the bacteria. Want milder bread? Keep it cool and don’t let it over-ferment.

The symbiosis is real. Bacteria produce compounds that stimulate yeast growth. Yeast creates conditions that favor certain bacterial strains. Remove one group, and the ecosystem collapses.

I maintain four different starters, each with its own character. One is aggressively sour, perfect for rye bread. Another is mild and sweet, great for sandwich loaves. Same feeding routine, but they diverged over time based on slight differences in flour and handling.

That’s the beautiful complexity of fermentation science for beginners who stick with it. Your starter becomes genuinely unique, shaped by your environment and your hands.

Practical Guide: Making Your First Ferment

Let me walk you through basic sauerkraut because it teaches you everything you need to know.

Ingredients and Ratios

One medium cabbage, about 900 grams after removing outer leaves and core. 18 grams of salt. That’s 2% salt by weight, which is the sweet spot for flavor and fermentation speed.

Some recipes call for 3% salt. That works too, but fermentation takes longer and the result tastes saltier. Maintaining humidity levels below 2% is crucial, as it allows beneficial bacteria to assert their dominance and prevents spoilage bacteria from gaining a foothold. This proactive measure ensures the quality and safety of your products. I stick with 2% for most ferments.

The Process

Shred your cabbage. While I often rely on a knife for my slicing needs, I find that a mandoline delivers exceptional results and efficiency. It’s a fantastic tool that can take your food preparation to the next level.. You want pieces about 3mm thick. Too thick and they stay crunchy forever. Too thin and they get mushy.

Combine cabbage and salt in a large bowl. Now massage it. Really work it with your hands for five to ten minutes. You’re crushing cell walls and releasing liquid. Keep going until you can squeeze a handful and see liquid pooling in your palm.

Pack everything into a jar. Press down hard to eliminate air pockets. The cabbage should be submerged under its own liquid by at least a centimeter. If you don’t have enough liquid, make a quick brine (2% salt in water) and add it.

Weight the cabbage down. I use glass weights made for fermenting, but a small jar filled with water works. The goal is keeping everything submerged.

Cover loosely. I use a lid set on top but not screwed down. This allows CO2 to escape while keeping out dust and insects.

What to Expect

Within 24 hours at room temperature (around 20°C/68°F), you should see tiny bubbles forming. That’s CO2 from active fermentation. The brine might get cloudy. That’s normal—it’s billions of bacteria multiplying.

After three days, taste it. Seriously, stick a clean fork in there and try it. It should taste lightly sour, less salty than on day one, still quite crunchy. The pH should be around 4.5. If you have pH strips, test it. Seeing that number drop is incredibly satisfying.

Continue fermenting for another four to eleven days, tasting every couple of days. When it reaches your preferred sourness, move it to the fridge. Cold temperatures slow fermentation dramatically but don’t stop it completely.

I usually ferment for seven to ten days total at 18°C to 20°C (64°F to 68°F). That gives me good flavor complexity without excessive sourness.

When Things Go Wrong (And They Will)

I’ve screwed up plenty of batches over the years. Here’s what I’ve learned from those mistakes.

The Silent Jar

Three days in and nothing’s happening? No bubbles, no smell, tastes exactly like salted cabbage? Temperature is usually the culprit. I once left a jar in my garage during November. Two weeks later, still nothing. Brought it inside to normal room temp and boom—bubbles within twelve hours.

If your house runs cold (below 15°C/59°F), fermentation crawls. Find a warmer spot. Top of the fridge sometimes works. Near the water heater. Anywhere consistently around 18°C to 22°C.

Salt can kill fermentation too. Last month I wasn’t paying attention and added three tablespoons instead of three teaspoons. Way too much. The bacteria couldn’t handle it. I tried diluting it with more cabbage but honestly, that batch was garbage. Just started over.

The Volcano Effect

Some jars explode with activity. Brine everywhere, bubbles pouring out when you open the lid. First time this happened, I thought I’d contaminated something. Nope. Just very enthusiastic heterofermentative bacteria producing massive amounts of CO2.

Not a problem, just annoying. I started burping those jars twice a day instead of once. Or I’d stick them in a cooler spot to calm things down. Kitchen counter in summer hits 26°C sometimes. Move it to the basement and the fizzing mellows out.

Funky Smells

Fermentation smells sour. Tangy. Like pickles sitting in vinegar. Sometimes cabbage gets a bit sulfur-y around day four, which freaks people out. But it’s still a vegetable smell, not a garbage smell.

If your ferment smells like actual death—rotten, putrid, like something crawled in there and died—something went very wrong. Toss it. I don’t mess around with genuinely foul-smelling ferments. Had one batch of turnips that smelled so bad I threw the jar out without even opening it all the way. Trust your gut on this.

The Mold Situation

White filmy stuff on top? That’s kahm yeast. Looks gross but won’t hurt you. I just scoop it off with a spoon and keep going. It can make things taste a little off, but it’s not dangerous.

Fuzzy mold in actual colors—green, black, sometimes pink—that’s real mold and it needs to go. Usually means something floated above the brine or you didn’t use enough salt. I’ve saved batches by scraping off the mold and the top layer of vegetables, but honestly? Just make a new batch. Cabbage is cheap.

The fix is dead simple: keep vegetables under the brine. Every single piece, all the time. That’s it.

Going Deeper: Stuff That’ll Blow Your Mind

After you’ve nailed basic sauerkraut, this is where fermentation science for beginners gets really interesting.

The Bacterial Relay Race

Different bacteria take over at different points. It’s like watching a relay race under a microscope.

Leuconostoc shows up first. Fast little buggers. They can handle higher salt and they pump out CO2 like crazy. Within two or three days, they’ve dropped the pH to around 4.5 and created the perfect environment for the next runners.

Then Lactobacillus plantarum takes the baton. These guys are acid-tolerant machines. They keep producing lactic acid, pushing the pH down to 3.5 or even lower. Different flavor compounds too—more complex, more depth.

Sometimes in really long ferments (we’re talking months here), you’ll get Lactobacillus brevis showing up. Super acid-tolerant. Creates these intense, funky flavors that some people love and some people hate.

Here’s the cool part: you can actually taste the succession. Day three sauerkraut tastes bright and simple—that’s Leuconostoc territory. Two-week sauerkraut gets more complicated—multiple bacterial species layering their metabolic products. Month-old kraut can be intensely complex, almost wine-like.

Playing With Salt

Salt percentage completely changes the game. I’ve spent embarrassing amounts of time testing different concentrations.

2% salt: Fast fermentation, lots of bacterial diversity, good flavor in seven to ten days. This is my everyday ratio.

2.5% salt: Slows things down, flavors get cleaner and more refined. Takes two weeks instead of one. Worth it for special batches.

3% salt: Fermentation takes forever but the end result is incredibly clean-tasting. Almost delicate. Takes three to four weeks.

I tried 5% once out of curiosity. Two months to acidify. Stupidly salty. Interesting experiment, wouldn’t do it again.

Below 2%, things get sketchy. I’ve had 1.5% batches that developed off-flavors because spoilage bacteria had too much opportunity before the good guys took over.

The Chemistry of Flavor

Temperature and time don’t just affect speed. They determine which volatile compounds get produced.

Cool fermentation (around 15°C) creates delicate, fruity esters. You get these subtle aromatics that disappear if you ferment hot. Some of my best sauerkraut happened accidentally in a cold basement—took three weeks but tasted incredible.

Hot fermentation (around 27°C) produces simpler, sharper flavor profiles. More lactic acid, fewer complex compounds. Gets sour fast but lacks depth.

Long fermentation breaks proteins down into individual amino acids. I sent two-month-old kimchi to a lab once. The glutamate levels were nuts—comparable to aged Parmesan. That’s where umami comes from in fermented foods.

Questions People Keep Asking Me

Is this thing safe to eat or am I going to die?

Smell it. Taste a tiny bit. If it smells pleasantly sour and tastes tangy, you’re fine. Your nose knows. I’ve made probably five thousand batches at this point and never gotten sick from a properly fermented vegetable.

The acid creates a hostile environment for pathogens. pH below 4.0 is basically a fortress. Bad bacteria can’t survive there. Your senses are incredibly good at detecting actual problems—rotten smells mean real trouble. Sour smells mean successful fermentation.

What about botulism? My aunt keeps warning me about botulism.

Your aunt doesn’t understand fermentation science for beginners. Clostridium botulinum needs three things: no oxygen (check), low acid (nope), and protein-rich environment (vegetables aren’t that).

Fermented vegetables are way too acidic. I’ve deliberately tried to culture C. botulinum in fermented cabbage in controlled lab settings. Can’t be done. The pH is too low. This is why humans have been fermenting vegetables for ten thousand years without refrigeration and without mass die-offs.

Should I buy starter cultures or just wing it?

For vegetables? Wing it. The bacteria you need are already there, living on the cabbage. I’ve literally swabbed organic cabbage leaves and cultured the bacteria. Tons of Lactobacillus plantarum just hanging out, waiting for the right conditions.

Commercial starters work, but they give you one or two bacterial species. Wild fermentation gives you maybe twenty species. More diversity equals more complex flavor. I never use commercial starters for vegetables. Never needed to.

Dairy is different. For yogurt or cheese, starters give you predictable results. But vegetables? Let them go wild.

How long can I keep this stuff?

I’ve got jars in my fridge that are over a year old. Still perfectly safe. Still taste good, though the texture changes—vegetables get softer over time, flavors mellow out a bit.

Most fermented vegetables hit their peak between two weeks and two months. After that they’re still fine, just different. Really acidic ferments like traditional sauerkraut can last six months easy. The acid keeps preserving them indefinitely as long as they stay cold.

I’ve eaten three-year-old kimchi from the back of my fridge. Was it the best kimchi I’ve ever had? No. Did it make me sick? Also no.

Will cooking kill all the good bacteria?

Yeah, heat kills them dead. Anything above 46°C (about 115°F) and you’re pasteurizing your ferment. No more live probiotics.

But here’s the thing: even cooked fermented foods are still nutritious. The vitamins the bacteria created are still there. The proteins they broke down are still pre-digested. The minerals are still more bioavailable. You lose the live cultures but keep most of the nutritional benefits.

I usually add sauerkraut to soup after I turn off the heat. Or use it as a garnish on hot food. That way it warms up but doesn’t actually cook, and the bacteria survive.

Where This Takes You

Learning fermentation science for beginners is really about seeing what’s invisible. Once you get that millions of living things are actively transforming your food through specific chemical reactions, the whole process clicks differently. You’re not following instructions anymore. You’re managing living systems.

Start with sauerkraut. Watch it do its thing. Taste it every day—literally stick a clean fork in there and see how it changes. Get some pH strips and watch the numbers drop from 6 to 4 to 3.5. That physical evidence of invisible microbial work is wild the first few times you see it.

Then mess around with other stuff. Kimchi is basically spicy sauerkraut with different vegetables. Sourdough bread is yeast and bacteria working together instead of separately. Yogurt is the same lactic acid bacteria but in milk instead of cabbage.

You’ll start noticing patterns after a while. That musty, yeasty smell means fermentation is active. Certain temperatures feel right for certain ferments just by watching how they behave. You develop this weird intuition about timing—you can look at a jar and just know it’s ready.

That’s what fermentation science for beginners is actually teaching you: how to read microbial systems. The bacteria and yeast have been doing this for billions of years. They don’t need you to make it work. You’re just setting up good conditions and staying out of their way.

I’ve been obsessed with this for fifteen years now. Still learning weird stuff with every batch. Two weeks ago I made turnip kraut and it developed this unexpected floral note I’ve never tasted before. Don’t know which bacterial species created it. Doesn’t matter—it was delicious. That’s the magic of working with wild, living fermentation.

You’re about to join a practice that’s older than agriculture, older than civilization, older than written language. Humans have been fermenting food for ten millennia. Welcome to it.