When you walk past that converted loft building downtown or grab coffee in what used to be a textile mill, you’re stepping through layers of American Labor Heritage that most people never notice. These aren’t just old buildings with exposed brick and high ceilings. They’re monuments to the people who built this country with their hands, their sweat, and sometimes their lives.

The story of American Labor Heritage isn’t something that lives only in textbooks or museums. It’s woven into the fabric of nearly every American town, waiting to be discovered by anyone curious enough to look. From the architecture that defines our neighborhoods to the rights we take for granted at work today, the labor movement shaped the country we live in now.

What Is American Labor Heritage and Why Does It Matter?

American Labor Heritage encompasses the history, struggles, and victories of working people who fought for dignity, fair wages, and safe working conditions. It includes the physical spaces where this history unfolded—factories, union halls, company towns—and the cultural legacy of labor organizing that transformed American society.

This heritage matters because it tells the story of ordinary people doing extraordinary things. It’s about immigrant families working 14-hour shifts in dangerous conditions, children as young as eight laboring in coal mines, and communities coming together to demand better. The eight-hour workday, workplace safety regulations, child labor laws, and the weekend itself all emerged from these struggles.

Most importantly, American Labor Heritage is local. Every town has its own story. That old brick building on Main Street might have been where a pivotal strike began. The park where you walk your dog could be named after a union organizer. These connections make history tangible and relevant.

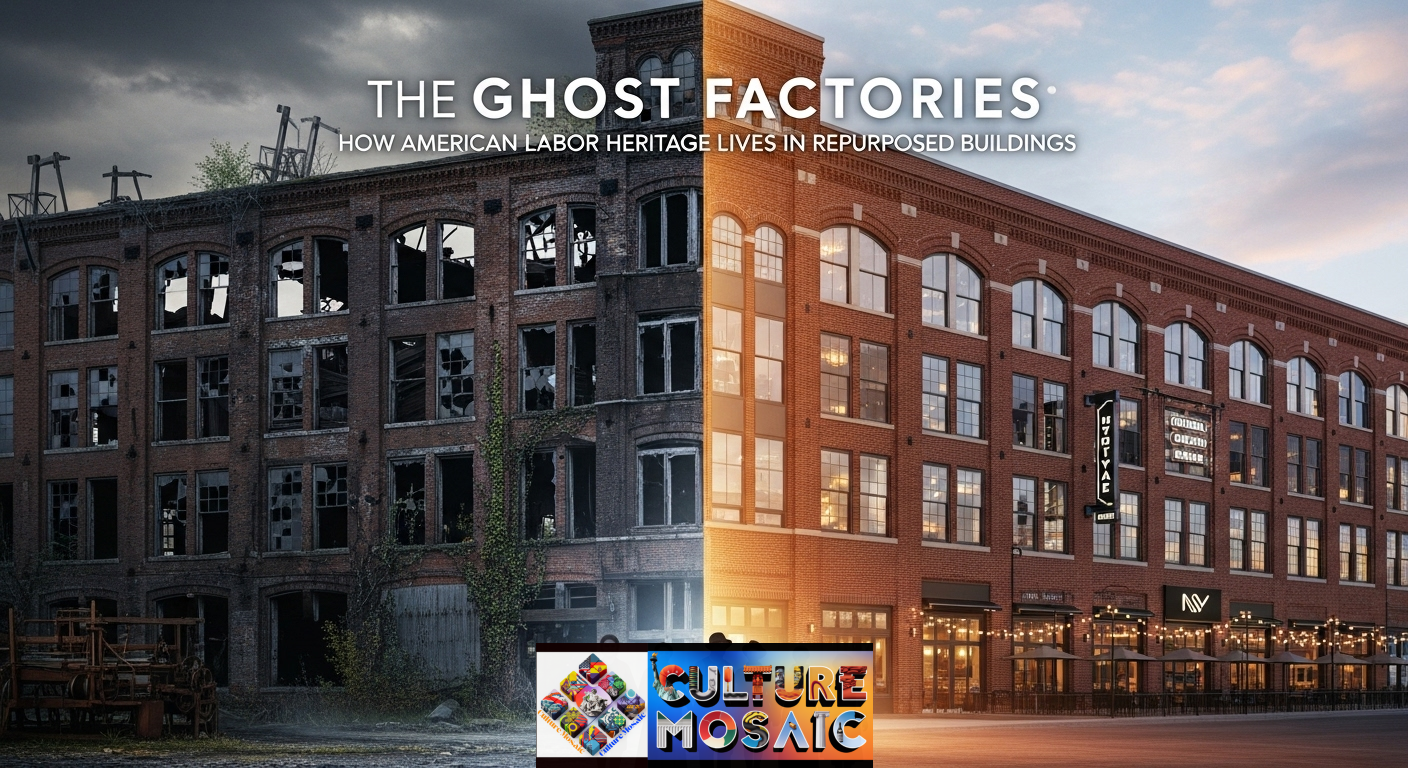

The Ghost Factories: How American Labor Heritage Lives in Repurposed Buildings

Drive through any American city and you’ll see them: massive brick structures with huge windows, now housing expensive apartments, trendy restaurants, or tech startups. These ghost factories are physical reminders of American Labor Heritage, even when their original purpose has been erased or romanticized.

Take Lowell, Massachusetts, where textile mills once employed thousands of young women known as the “Mill Girls.” These workers, many barely teenagers, lived in boarding houses and worked 12-hour days amid deafening machinery. They also organized some of the first labor protests in American history, walking out in 1834 and 1836 to protest wage cuts. Today, those same mill buildings house upscale condos and small businesses. The architecture remains, but the stories of the people who worked there are often forgotten.

In Pittsburgh, the old steel mills that defined the city’s identity for generations have been transformed into shopping centers and office parks. During their heyday, steelworkers faced brutal conditions, extreme heat, and constant danger. The labor movement in Pittsburgh was particularly fierce, with strikes in 1892 and 1919 that changed American labor law forever. When you shop in a converted mill building, you’re walking where immigrant workers from Poland, Italy, and Eastern Europe once forged the steel that built American cities.

The same pattern repeats across the country. North Carolina’s tobacco warehouses are now art galleries. Detroit’s auto plants host farmers’ markets. These repurposed spaces are economically valuable, but they also represent an opportunity to reconnect with American Labor Heritage. Some cities are getting this right by installing historical markers, hosting heritage tours, or preserving small sections of buildings in their original state.

The Silent Strike Heroes: Forgotten Labor Actions That Changed Everything

American Labor Heritage includes countless strikes and labor actions that never made it into national history books but fundamentally changed their communities. These “silent strikes” often involved marginalized workers—women, Black Americans, immigrants—whose contributions have been systematically overlooked.

The 1909 Uprising of 20,000 in New York City saw young women garment workers, mostly Jewish and Italian immigrants, walk off their jobs demanding better conditions. They picketed in freezing weather, faced police violence, and were ridiculed in the press. Yet they held out for months, eventually winning better wages and conditions. This strike inspired other labor actions and laid the groundwork for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. The women who led this fight—Clara Lemlich, Rose Schneiderman—became legends, but thousands more remain nameless.

In Memphis in 1968, sanitation workers went on strike with signs reading “I Am a Man.” This wasn’t just about wages, though the Black workers were paid poverty-level salaries. It was about dignity and civil rights. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to support the strike and was assassinated in Memphis during this campaign. The strike succeeded, but it took two months of determination and sacrifice that most people outside Memphis have never heard about.

California’s Delano Grape Strike began in 1965 when Filipino farmworkers walked out of vineyards, soon joined by Mexican workers organized by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. For five years, farmworkers and their supporters boycotted grapes nationwide, bringing attention to the exploitative conditions faced by agricultural workers. This movement created lasting change in farmworker rights and became a central part of American Labor Heritage in the Southwest.

These silent strikes happened everywhere. Coal miners in Appalachia, meatpackers in the Midwest, cannery workers in the Pacific Northwest—each region has its own labor heroes whose names might not be nationally known but whose courage changed lives.

The Company Town to Modern Suburb Pipeline

One of the most fascinating aspects of American Labor Heritage is the company town—entire communities built and controlled by a single corporation. These towns shaped American infrastructure and class dynamics in ways that still affect us today.

Company towns emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when industries needed workers in remote locations. Coal companies in West Virginia, textile manufacturers in New England, and logging operations in the Pacific Northwest built entire towns: houses, stores, schools, even churches. Workers lived in company housing, shopped at company stores, and often were paid in company scrip that could only be spent locally.

Pullman, Illinois, built by railroad car manufacturer George Pullman in the 1880s, was meant to be a model company town. Pullman believed that if workers lived in beautiful, orderly surroundings, they’d be more productive and less likely to organize. Instead, workers resented the control and high rents. When Pullman cut wages but not rent during an economic depression, workers struck. The Pullman Strike of 1894 became one of the most significant labor conflicts in American history and led to federal intervention.

Hershey, Pennsylvania, tells a different story. Milton Hershey built his town with better intentions, providing good housing and amenities. Still, it was fundamentally about control. When workers tried to unionize in 1937, violence erupted. The company town model, even when benevolent, created a power imbalance that defined American Labor Heritage.

Many company towns don’t exist anymore, at least not in their original form. But their influence lingers. The physical layout of some modern suburbs directly mirrors company town planning. More importantly, the economic dependence of communities on single employers—think Amazon in Seattle or tech companies in the Bay Area—echoes the company town dynamic. When one corporation dominates a region’s economy, workers face limited options, just as they did a century ago.

American Labor Heritage shows us this pattern repeating. Understanding company towns helps us recognize similar dynamics today and why worker power matters for community health.

Finding American Labor Heritage in Your Own Backyard

The most exciting thing about American Labor Heritage is that you can discover it where you live. Labor history isn’t abstract—it’s local, and traces of it are everywhere once you know what to look for.

Start with buildings. Old factories, warehouses, and industrial sites are obvious markers, but also look for union halls, some of which still operate. In many cities, union halls were social centers where workers gathered for meetings, classes, and cultural events. These buildings often feature labor-themed artwork, plaques commemorating strikes or organizing victories, and architectural details that reflect working-class aesthetics.

Historical markers and plaques are scattered throughout American communities, often in unexpected places. A park might be named after a labor organizer. A street might commemorate a significant strike. State historical societies maintain databases of markers, and many are specifically about labor history. The problem is that these markers are easy to overlook. Making a point to read them can reveal the American Labor Heritage you walk past every day.

Museums dedicated to labor history exist across the country. The American Labor Museum in New Jersey occupies the home of Pietro and Maria Botto, whose house hosted the key meeting of the 1913 Paterson Silk Strike. The Labor and Industry Museum in Belleville, Illinois, preserves the story of coal mining and other industries that built the region. Seattle has a Labor Temple that hosts events and exhibits. These institutions do vital work preserving American Labor Heritage and making it accessible.

Cemeteries might seem like an unlikely place to explore labor history, but they often contain the graves of union organizers, strike leaders, and workers who died in industrial accidents. Some labor movements held elaborate funerals for fallen workers, and these graves became sites of remembrance. Haymarket Martyrs’ Monument in Chicago honors labor activists executed after the Haymarket Affair of 1886. Walking through older cemeteries with an eye toward labor history can be surprisingly revealing.

Oral history projects and local archives are treasure troves of American Labor Heritage. Many public libraries and historical societies have collected interviews with former factory workers, miners, and union members. These firsthand accounts bring labor history to life in ways that official documents never could. They’re also often underutilized resources. Spending an afternoon in local archives can uncover stories about your own town that few people know.

Digital resources make exploring American Labor Heritage easier than ever. The Library of Congress has extensive online collections of labor photographs, documents, and oral histories. State labor history associations often maintain websites with interactive maps, timelines, and teaching resources. Social media groups focused on local history frequently discuss labor heritage, sharing old photographs and personal memories.

American Labor Heritage and Contemporary Worker Movements

Understanding American Labor Heritage isn’t just about looking backward. It provides context for contemporary labor movements and workplace issues that dominate headlines today.

The recent surge in union organizing at major corporations—Amazon warehouses, Starbucks stores, Apple retail locations—echoes patterns from a century ago. Workers at these companies face many of the same issues their predecessors did: demanding schedules, surveillance, retaliation for organizing, and wages that don’t keep up with living costs. The tactics are similar too: building solidarity, public campaigns, leveraging media attention.

What makes this resurgence particularly interesting from an American Labor Heritage perspective is that it’s happening in sectors once considered impossible to organize. Service workers, retail employees, and tech workers weren’t traditionally union strongholds. This mirrors the industrial organizing of the 1930s, when the Congress of Industrial Organizations successfully unionized mass production industries that craft unions had ignored.

The language of today’s labor movement also draws directly from American Labor Heritage. When workers talk about dignity, respect, and basic rights, they’re using the same vocabulary as the Memphis sanitation workers or the Lowell Mill Girls. The connection between labor rights and civil rights, so apparent in movements like the 1968 sanitation strike, remains central to modern organizing, particularly for workers of color and immigrants.

Gig economy workers—rideshare drivers, delivery workers, freelancers—face challenges that seem new but actually have deep roots in American Labor Heritage. These workers often lack basic protections, face unpredictable income, and have little power to negotiate with platforms that control their work. This situation resembles the piecework system of the garment industry or the casual labor system in longshore work, both of which labor movements eventually addressed through collective action.

Climate change and the transition to green energy create new dimensions for American Labor Heritage. Workers in fossil fuel industries understandably worry about their livelihoods. Labor history shows that economic transitions always impact workers hardest unless movements fight for just transition policies. The concept of a “just transition”—ensuring workers aren’t left behind during economic shifts—comes directly from labor movement principles.

Why American Labor Heritage Belongs in Every Community Conversation

When communities discuss development, historic preservation, economic policy, or education, American Labor Heritage should be part of the conversation. Here’s why it matters beyond academic interest.

Economic development often focuses on attracting businesses and investment, but American Labor Heritage reminds us that workers built the prosperity we enjoy. When cities offer tax breaks to corporations, they’re making choices about whose interests matter most. Understanding labor history helps communities ask better questions: What kind of jobs will this create? What will they pay? Will workers have a voice?

Historic preservation tends to focus on grand homes, government buildings, and sites associated with famous people. American Labor Heritage argues for preserving working-class history too. The union hall, the strike site, the factory where people spent their lives—these places matter. They tell a more complete and honest story about American history.

Education about American Labor Heritage gives young people a more accurate understanding of how change happens. Too often, history curricula present progress as inevitable or the result of enlightened leaders’ decisions. Labor history shows that workers organized, sacrificed, and fought for every advance. That’s an empowering message.

Tourism and cultural heritage initiatives increasingly recognize that American Labor Heritage attracts visitors and creates authentic experiences. Heritage tourism built around labor history—factory tours, labor history trails, annual commemorations of significant strikes—can be economically valuable while honoring the past.

Preserving American Labor Heritage for Future Generations

American Labor Heritage faces real threats. Old buildings get demolished. Documents are lost. People with firsthand memories pass away. If we don’t actively preserve this history, it disappears.

Documentation is crucial. Local historians, archivists, and volunteers do essential work collecting photographs, documents, and oral histories before they’re gone. Supporting these efforts—through funding, donations of materials, or volunteering—helps preserve American Labor Heritage for future generations.

Digital preservation makes labor history more accessible. Scanning documents, digitizing photographs, and recording oral histories ensure these materials survive and can be widely shared. Many local labor councils and historical societies need help with digitization projects.

Education initiatives bring American Labor Heritage into schools and public programs. Teaching local labor history makes the subject relevant to students and instills pride in working-class heritage. Some unions and labor organizations offer curriculum materials and guest speakers for classrooms.

Physical preservation of labor-related sites matters enormously. When historic factories or union halls face demolition, communities should consider whether they can be preserved or whether, at a minimum, their history can be documented and memorialized. Adaptive reuse projects that maintain historical elements while creating new uses offer a good compromise.

Public art and memorials keep American Labor Heritage visible. Murals, sculptures, and installations that honor workers and labor movements remind communities of their history. These need not be grand or expensive. Even a simple marker or plaque makes a difference.

Storytelling brings American Labor Heritage to life. Podcasts, documentaries, articles, and social media projects that tell labor stories in engaging ways reach new audiences. Personal narratives—workers’ own words about their experiences—are particularly powerful.

The Living Legacy of American Labor Heritage

American Labor Heritage isn’t dead history. It’s alive in every workplace, right, every union contract, every conversation about fair wages and working conditions. The people who fought these battles left us more than stories. They left us tools, strategies, and inspiration.

When you learn that your weekend exists because workers organized and struck for it, the weekend means something different. When you discover that your town’s beautiful park was once the site of a violent clash between strikers and company guards, you see that space differently. When you realize the apartment building you admire was a factory where children once worked on dangerous machinery, architecture takes on new meaning.

This is what American Labor Heritage offers: a deeper, richer understanding of the world around us. It complicates simple narratives and asks us to see familiar places through different eyes. It honors people who were never famous but whose courage and determination changed the course of history.

Every town has these stories. Every community has its labor heritage. The question is whether we’ll take the time to discover it, preserve it, and pass it on. Because when we forget where workers’ rights came from, we risk losing them. When we ignore the lessons of American Labor Heritage, we’re condemned to repeat old mistakes.

The converted factory on your street, the historical marker you never noticed, the name of a park whose origin you never questioned—start looking at them differently. Behind each one is a story of real people fighting for dignity and justice. That’s American Labor Heritage, and it’s everywhere.

Frequently Asked Questions About American Labor Heritage

What exactly is included in American Labor Heritage?

American Labor Heritage includes the physical sites where labor history occurred (factories, union halls, strike locations), the stories of workers and labor movements, the cultural traditions that emerged from working-class communities, and the lasting impact of labor organizing on American law and society. It encompasses everything from major strikes that made national news to the daily experiences of ordinary workers whose names we’ll never know.

How can I find labor history sites in my area?

Start by contacting your local historical society or public library, which often maintain archives and can point you toward labor history resources. State labor councils and union offices sometimes offer heritage tours or have information about local sites. Online resources like the Library of Congress, state historical markers databases, and labor history websites provide searchable information. Walking tours focused on labor history exist in many cities and offer guided exploration of important sites.

Why isn’t American Labor Heritage taught more widely in schools?

Labor history has been systematically underrepresented in American education for complex reasons, including political considerations, standardized curriculum pressures, and historical bias toward the perspectives of business and political leaders rather than workers. Many educators want to teach more labor history but lack resources, training, or curriculum materials. This is changing as more people recognize the importance of teaching complete, honest history that includes working-class perspectives and the reality of how social change happens through collective action.

Is American Labor Heritage only relevant to people in unions?

Absolutely not. American Labor Heritage affects everyone who works because labor movements created workplace protections that we all benefit from, whether we’re union members or not. The 40-hour work week, overtime pay, workplace safety regulations, child labor laws, minimum wage, employer-provided health insurance, and many other standards came from labor organizing. Understanding this history helps all workers recognize their rights and the importance of protecting them, regardless of union membership.

How does American Labor Heritage connect to current workplace issues?

The patterns, strategies, and challenges visible in American Labor Heritage directly parallel contemporary workplace struggles. Modern organizing campaigns at companies like Amazon and Starbucks use tactics developed a century ago. Debates about gig economy worker classification echo historical fights over how to define employment. Concerns about automation and job loss mirror anxieties workers faced during previous technological transitions. Understanding labor history provides context for current events and reveals that today’s workplace conflicts are part of ongoing, long-term struggles over worker power and dignity.